Wastewater dashboard adds monkeypox, flu and more for five southeast Michigan communities

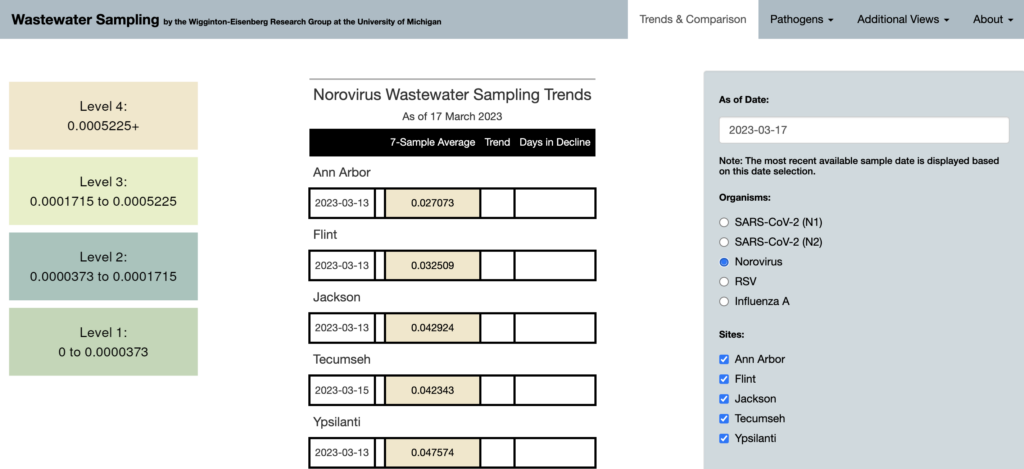

The results of monitoring for diseases beyond COVID-19 are now publicly available for Ann Arbor, Flint, Jackson, Tecumseh and Ypsilanti.

The results of monitoring for diseases beyond COVID-19 are now publicly available for Ann Arbor, Flint, Jackson, Tecumseh and Ypsilanti.

A public dashboard that tracks pathogens detected in wastewater just added monitoring for monkeypox, influenza-A, norovirus GII and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) today. The project, which has been providing information about community COVID-19 levels through wastewater monitoring since 2021, is a collaboration between researchers in civil and environmental engineering and public health at the University of Michigan.

Funded by The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS), the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and the University of Michigan, the team collects and tests water samples from five local wastewater treatment plants: Ann Arbor, Flint, Jackson, Tecumseh and Ypsilanti. Trend and comparison data are shared in biweekly meetings with partners and funders. It is also publicly available online.

“By having access to this information, people can make informed decisions about their behavior if they have a personal concern about the levels of pathogens detected in their community,” said Krista Wigginton, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering and co-leader of the project.

The information can guide public health responses at locations with high risk of disease transmission, such as schools and retirement homes. For example, teachers might focus on more rigorous classroom cleaning protocols if they know human norovirus cases are rising in their district, or parents might see that RSV levels are growing in their community, prompting them to take additional precautions regarding their young children’s potential exposure risks.

“People often don’t seek clinical testing or see a doctor for the flu, RSV, or norovirus, so wastewater monitoring gives public health officials and clinicians a way to understand how the transmission patterns of these diseases are changing and to get an early warning of new transmission,” said Marisa Eisenberg, a project co-lead and professor of epidemiology.

While case data was most widely publicized during the COVID-19 pandemic, the emergency turned into a proving ground for wastewater monitoring for numerous diseases. The U-M team had been building the infrastructure and streamlining the process for collecting and analyzing wastewater even before the pandemic.

“Methods developed for COVID-19 can be applied to a number of other infectious diseases of public health concern,” Betsy Foxman, the Hunein F. and Hilda Maassab Professor of Epidemiology and director of the Center for Molecular and Clinical Epidemiology of Infectious Diseases at the U-M School of Public Health.

“We are working to apply our methods to monitor adenovirus, polio, rotavirus, Candida auris and antibiotic-resistant bacteria like MRSA,” she added.

MRSA, a common staph infection known as a superbug, is seen as a serious global health threat by the CDC, and the recent, ongoing rise in drug-resistant Candida auris, a fungal infection, is also of concern to the CDC and healthcare providers.

By looking for genetic code from pathogens, wastewater monitoring can potentially screen for dozens of pathogens at a time. A sample of wastewater effectively tests people across the community, offering anonymity as well as a broad sweep of the diseases circulating. And unlike case counts, wastewater monitoring catches everyone who uses toilets in the sewershed.

“We trust the data a lot now, and we think it’s time to show the broader community that it’s here. When a new threat comes around, we have the infrastructure ready and can therefore adapt methods to start looking for it, and I think that’s really valuable to the public,” Wigginton said.

“There are many other teams across the state that are looking at other regions. The state is ensuring that different labs are using the same methods, the same types of instruments and the same protocols. This allows the state to combine the data from regions throughout the State of Michigan and compare levels and trends,” she added.

Michelle Ammerman, an assistant research scientist in civil and environmental engineering, is another project co-lead. Eisenberg is also a professor of complex systems and mathematics.

This project is supported through 2024 with grants from MDHHS’s SEWER Network Program, the CDC’s SAPPHIRE Program, and internal funding from the University of Michigan.

Story by Michele Santillan