A laser pointer could hack your voice-controlled virtual assistant

Researchers identified a vulnerability that allows a microphone to ‘unwittingly listen to light as if it were sound’

Researchers identified a vulnerability that allows a microphone to ‘unwittingly listen to light as if it were sound’

From a distance of more than 300 feet and through a glass window, a laser beam can trick a voice-controlled virtual assistant like Siri, Alexa or Google Assistant into behaving as if it registered an audio command, researchers from the University of Michigan and University of Electro-Communications in Tokyo have demonstrated.

The researchers ‘climbed 140 feet to the top of a bell tower at the University of Michigan and successfully controlled a Google Home device on the fourth floor of an office building 230 feet away.’

The New York Times | Ars Technica | NBC Nightly News

The researchers discovered in the microphones of these systems a vulnerability that they call “Light Commands.” They also propose hardware and software fixes, and they’re working with Google, Apple and Amazon to put them in place.

“We’ve shown that hijacking voice assistants only requires line-of-sight rather than being near the device,” said Daniel Genkin, assistant professor of computer science and engineering at the University of Michigan. “The risks associated with these attacks range from benign to frightening depending on how much a user has tied to their assistant.

“In the worst cases, this could mean dangerous access to homes, e-commerce accounts, credit cards, and even any connected medical devices the user has linked to their assistant.”

The team showed that Light Commands could enable an attacker to remotely inject inaudible and invisible commands into smart speakers, tablets and phones in order to:

Just five milliwatts of laser power—the equivalent of a laser pointer—was enough to obtain full control over many popular Alexa and Google smart home devices, while about 60 milliwatts was sufficient in phones and tablets.

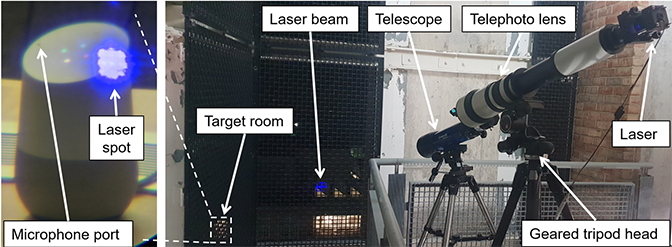

To document the vulnerability, the researchers aimed and focused their light commands with a telescope, a telephoto lens and a tripod. They tested 17 different devices representing a range of the most popular assistants.

“There is a semantic gap between what the sensors in these devices are advertised to do and what they actually sense, leading to security risks,” said Kevin Fu, associate professor of computer science and engineering at U-M. “In Light Commands, we show how a microphone can unwittingly listen to light as if it were sound.”

Users can take some measures to protect themselves from Light Commands.

“One suggestion is to simply avoid putting smart speakers near windows, or otherwise attacker-visible places,” said Sara Rampazzi, a postdoctoral researcher in computer science and engineering at U-M. “While this is not always possible, it will certainly make the attacker’s window of opportunity smaller. Another option is to turn on user personalization, which will require the attacker to match some features of the owner’s voice in order to successfully inject the command.”

Other researchers involved are: Takeshi Sugawara of the University of Electro-Communications in Tokyo and Benjamin Cyr, a doctoral student in computer science and engineering at U-M.