Reconstructive surgery tech

Born in an engineering class, now the ‘arterial everter’ has been licensed to Baxter.

Born in an engineering class, now the ‘arterial everter’ has been licensed to Baxter.

A new surgical device developed at the University of Michigan could make it quicker and easier to connect arteries in complicated procedures such as reconstructing a breast after mastectomy, or a severely injured leg after a car accident.

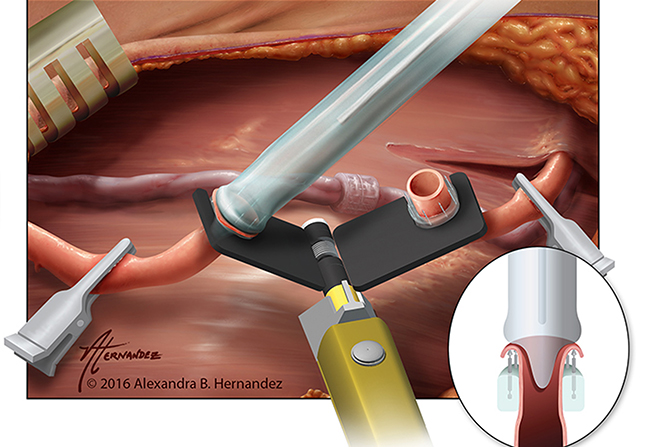

The “arterial everter” surgical device, which began as a project in an undergraduate class at Michigan Engineering, looks like a thin silicone pen with a flexible steel spine.

A new, preliminary study showed that the everter could turn a 20-minute process to connect arteries into one that takes five, and may not require a surgical microscope. The savings in time would add up, as surgeons must often connect more than one artery in a patient.

The preclinical study was recently published in the Journal of Reconstructive Microsurgery.

“The device simplifies what can be a technically challenging operation,” said Adeyiza Momoh, associate professor of surgery at the U-M Medical School. “If I can shave off an hour from my operative time, patients stand to benefit from being under anesthesia for a shorter period of time and the health system as a whole benefits because we are spending less time in the OR.”

The everter device works as an accessory to a currently available tool for connecting blood vessels, the GEM Microvascular Anastomotic Coupler system, made by Synovis Micro Companies Alliance Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of global medical products company Baxter International Inc.

U-M and Baxter recently signed a licensing agreement for the expected future marketing and distribution of the everter device globally.

Today, the GEM coupler works well on veins but the more muscular walls of arteries can make them harder to maneuver. The new everter is designed to help surgeons spread the thicker arterial walls over the rings of the GEM coupler, enabling the approach to be used to connect arteries.

Before the device can be used in surgeries, Baxter will need to file for FDA and other approvals.

The students developed great initial breakthroughs in function.

Jeffrey Plott, research fellow, mechanical engineering

“We are actively looking for technology partnerships to bring to market innovative solutions that solve challenges in the operating room,” said Michael Campbell, vice president of Baxter’s microsurgery business. “We are excited to work with the experts at the University of Michigan and license this promising new technology that could lead to a meaningful impact for microsurgeons.”

The tool began as a classroom project. Paul Cederna, professor and chief of the Section of Plastic Surgery at the U-M Medical School, has long been familiar with the arduous process of hand-sewing tiny, 1- to 3-millimeter arteries in complex tissue transfers. Cederna is also a professor of biomedical engineering, and he envisioned that this might be an ideal problem for U-M’s engineering design students.

He brought the challenge to Mechanical Engineering 450, a senior-level course he was co-teaching with Albert Shih, a professor of mechanical engineering.

“The students developed great initial breakthroughs in function,” said Jeffrey Plott, a research fellow in mechanical engineering who was then a doctoral student in Shih’s lab. Plott served as the product development mentor on the project.

“The initial designs were too complicated for ideal use in the operating room. Building on that early success, we were able to work with surgeons to streamline the concept and turn it into a potential commercial product.”

The Coulter Translational Research Partnership Program, housed in U-M’s Department of Biomedical Engineering, played a key role in taking the device from the lab to the marketplace. The program provides funding and expertise to accelerate the development of U-M technologies into new products that improve health care. Coulter provided funding for product design and testing.

“The everter is an example of how the entrepreneurial ecosystem at U-M supports biomedical innovation,” said Bryce Pilz, director of licensing for the U-M Office of Technology Transfer. “Projects at U-M benefit from schools that are top in their respective areas, have great researchers, and have also invested heavily in commercializing research.”