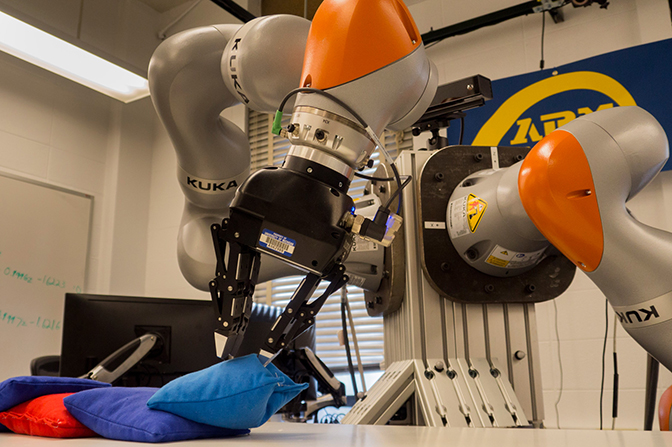

The beanbag test

It’s one thing for a robot to sort through a pile of rigid objects like blocks, but what about softer stuff?

It’s one thing for a robot to sort through a pile of rigid objects like blocks, but what about softer stuff?

Alright, so a robotic arm picking up beanbags from a pile and depositing them to the side until it grasps its target color might not seem hard to you. But it is the beginning of an important skill that will be crucial to robotic aid in industries, homes and emergencies.

Who hasn’t rifled through a basket of laundry to get some garment or other, or a box of tools to find the right one for the job? We do these things without thinking much about them, but for robots, they represent a trifecta of challenging tasks in the field of autonomy: perception, planning and manipulation.

Can it see the object it wants? What is in the way, between it and the object? Where should those other objects go, and how should they get there? And finally, how should it pick up the object it wants? The beanbag experiment is a proving ground.

“Here, the red beanbag is the one we want to grasp,” said Dmitry Berenson, an assistant professor of electrical engineering and computer science. “This is actually a very difficult task even though it seems a little bit simple to people, because perceiving which beanbags are overlapping which other ones is not easy.

“Sequencing the right amount of actions to get to the red beanbag efficiently is also not easy because we need to think about the relationships between the different beanbags.”

Beanbags are squishy, but they can’t deform as wildly as a shirt or a hose can. This variability in how a material can appear is a huge challenge for robots – they need to recognize the object before they can even begin to manipulate it. So the beanbags represent a step toward a robot that has human-like ease with all types of materials.

Berenson’s group handles the manipulation and motion planning aspects of the challenge in the Autonomous Robotic Manipulation (ARM) lab.

“The big challenges in motion planning are to determine the layout of how different objects are placed in the current scene, such as which is on the top of what, and the criteria to determine which object will be selected for removal so that it reveals more graspable area. Our Next Best Option planner solves these challenges,” said Vinay Pilania, a post-doctoral researcher in electrical engineering and computer science.

Meanwhile, the group of Jason Corso, an associate professor of electrical engineering and computer science, is developing the system that enables the robot to perceive the beanbags and other aspects of its environment, with leadership from Brent Griffin, an assistant research scientist in electrical engineering and computer science.

Whether they work in hospital laundry rooms or homes, help rescue people from disasters or set up a greenhouse on Mars, robots will need the skills that Berenson and Corso’s groups are testing out.

Other researchers on the project include:

This work was supported by the Toyota Research Institute, grant N022850.