Onto something

Amy Cohn’s unconventional approach to solving healthcare problems starts with students. It’s an approach that is gaining ground—at Michigan Medicine and beyond.

Amy Cohn’s unconventional approach to solving healthcare problems starts with students. It’s an approach that is gaining ground—at Michigan Medicine and beyond.

Story by Randy Milgrom, photos by Marcin Szczepanski

The unique trajectory that has materialized at Michigan began two decades ago. Amy Ellen Mainville Cohn, Alfred F. Thurnau Professor in Industrial and Operations Engineering and faculty director of the Center for Healthcare Engineering and Patient Safety (CHEPS), earned her PhD in Operations Research from Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2002. And though she had never lived more than 60 miles from her family—and by her own admission barely knew the difference between Michigan and Minnesota—she somehow suddenly found herself on the Michigan Engineering faculty.

“Michigan did a wonderful job recruiting us,” Cohn says now, referring to her entire family, which at that time included a husband and a toddler. “It was 20 years ago…. There was only one woman in the department and she didn’t have children. There were very few senior women at the College.” Yet Cohn credits Larry Seiford, then-chair of Industrial and Operations Engineering, for understanding what would make her and her family comfortable during a visit. And she was made to feel at home.

Cohn credits former dean of Michigan Engineering Dave Munson and former dean of Michigan Medicine James Woolliscroft—“good buddies and collaborators”—for understanding that operations engineering skills, primarily applied in the automotive, manufacturing, and transportation fields, could have even greater impact in healthcare. They worked with Jim Bagian, IOE professor of engineering practice, who had been founding director of the National Center for Patient Safety at the Veterans Affairs Hospital System (as well as a medical doctor and a former astronaut)—and who has since become co-director of the Center for Risk Analysis Informed Decision Making—to devise a sustainable course. They agreed to co-fund CHEPS, and they brought on Cohn to help further develop and execute the plan.

Gene Kim was the first person hired at CHEPS. “In the first year or two, there were no students,” Kim says. “We just started introducing ourselves across the University: ‘This is the frontier we want to be a part of—taking engineering tools and bringing them into the clinical work-space to try to make things safer. Do you have any problems or issues you’d like us to address?’”

Once CHEPS gained a foothold, Cohn developed a Health and Patient Safety (HEPS) concentration within the IOE master’s degree. The first semester, there were four CHEPS students. One of them was Billy Pozehl.

“Amy says as [an undergraduate] student I sat in the back and didn’t pay attention,” Pozehl says, “so her story differs from mine a little bit there.” But that bit of teasing aside, Pozehl says that “Amy is all about ensuring that everyone is engaged and on the same page…. [S]he truly wants everyone to learn the material.”

Cohn credits her faculty advisor during her days as an applied math undergraduate student at Harvard University for helping to shape what would become her own teaching style at CHEPS. After graduation, Cohn traveled to places like Fort Smith, Ark., struggling to teach trucking executives how to use the computer software products her employer had sold them.

“Here I was, this girl… in the trucking industry with my Harvard degree, trying to explain these complicated ideas to guys who had grown up with mainframes,” Cohn says. “They… didn’t want to say to me, ‘I don’t know how to do what you just did.’” But they weren’t confused by the concepts as much as by certain basic laptop functions.

“I think that was really valuable for my teaching,” Cohn explains, “to understand that when someone is struggling, you need to really dig to find out what the real problem is.”

At Harvard, she recalls having the rare opportunity—and formative experience—of being among “undergrads sitting with a master’s or PhD student, building a relationship of trust and comfort to go to them not just for technical work but also for advice about other things. And… feeling like you are being helpful to someone you’re mentoring is good for the grad students, too.”

This structured form of mentoring has been a hallmark at CHEPS.

And as it turns out, Pozehl was a pretty good student, because after he set the curve on a test, Cohn asked him to create practice problems for the course. When Pozehl was about to graduate in 2013, he told Cohn he wasn’t thrilled with any of his several job offers. So she suggested he stay on for a while in a research role—and he’s been at CHEPS ever since. Now a CHEPS research area specialist, Pozehl works closely as a mentor to individual students and as a leader of student project teams.

Pozehl first worked with thoracic surgeons to create a model that would enable residents to become adequately trained in several types of relatively infrequent, mostly unscheduled transplant procedures. Next was transforming residency shift schedules at the pediatric emergency department, so that what had required 30 hours every month to build manually is now accomplished by computer in seconds.

Michigan Medicine educator Brian George says he’d been struggling with how to create a “competency-based” medical education system that would enable residents to progress according to their abilities. Scheduling had always been the roadblock—but then “I heard from others about this amazing engineer who was one of the world’s experts in… scheduling! I couldn’t believe my luck in finding Amy.”

Within four or five years, CHEPS had grown (largely through this sort of word of mouth) to about 25 students, and Pozehl estimates that approximately 30% to 40% of Michigan Medicine residents are now being scheduled to some extent using CHEPS scheduling tools. Critical to supporting that growth, Pozehl says, was not just building the tools and giving them time to be successful but also developing the internal systems needed to work on so many different projects simultaneously.

Even with students who are changing every couple of semesters, Pozehl is able to bring in similar projects and implement them using internal support tools and onboarding documentation—and “the infrastructure for the code itself is very user-friendly. You don’t need to be a computer science grad to understand the code. Nursing students can contribute to it.”

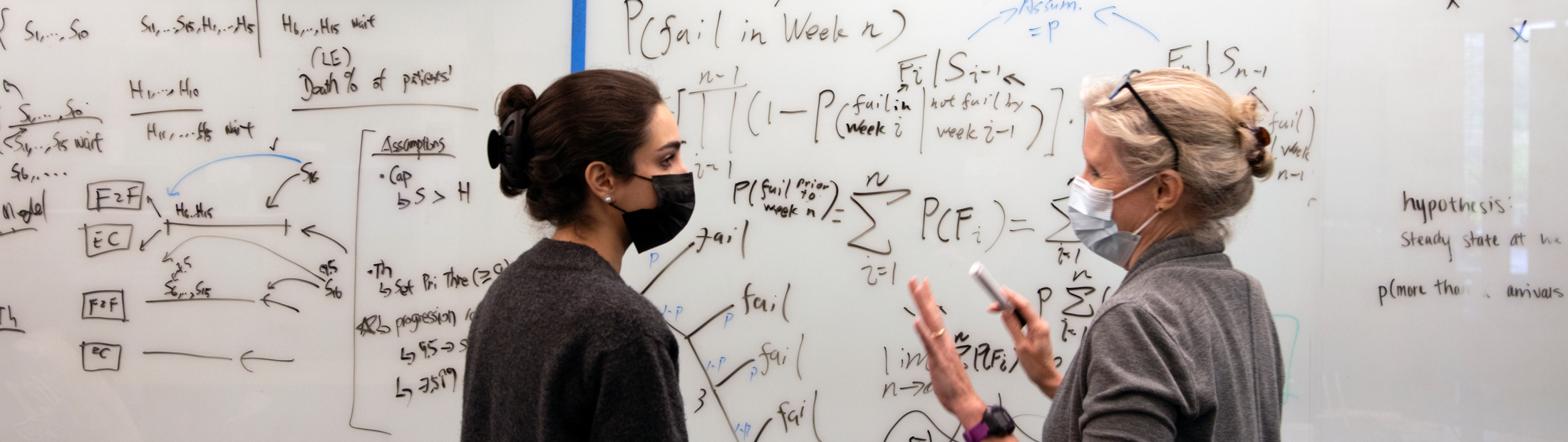

Kim—his formal title is administrative assistant, but he refers to himself as CHEPS’ “mascot, or cheerleader”—says that while many CHEPS students are from within IOE and computer science, others hail from public health, nursing, business, medicine, pre-med, and myriad LSA departments.

Donald Richardson first learned about CHEPS as an undergraduate at the University of Maryland-Baltimore County through the Summer Research Opportunity Program (SROP). That Ann Arbor summer of 2013 included work on the transplant scheduling project, as well as a simulation investigating variables that affect pediatric asthma patients’ lengths of stay.

“After that first summer I knew. Where did I want to apply math? In the healthcare space,” Richardson says. He returned to Michigan the following year and got involved with a Cancer Center project concerning the pre-mixture of chemotherapy drugs that became the focus of his PhD dissertation. Richardson earned his PhD in industrial and operations engineering in 2019 and has since been at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab (APL), doing work that is “very much related” to what he did at CHEPS.

“CHEPS is where I learned to break down and understand an audience and discuss complex problems,” Richardson says. “And the opportunity to work in such a collaborative environment as a student is unparalleled.”

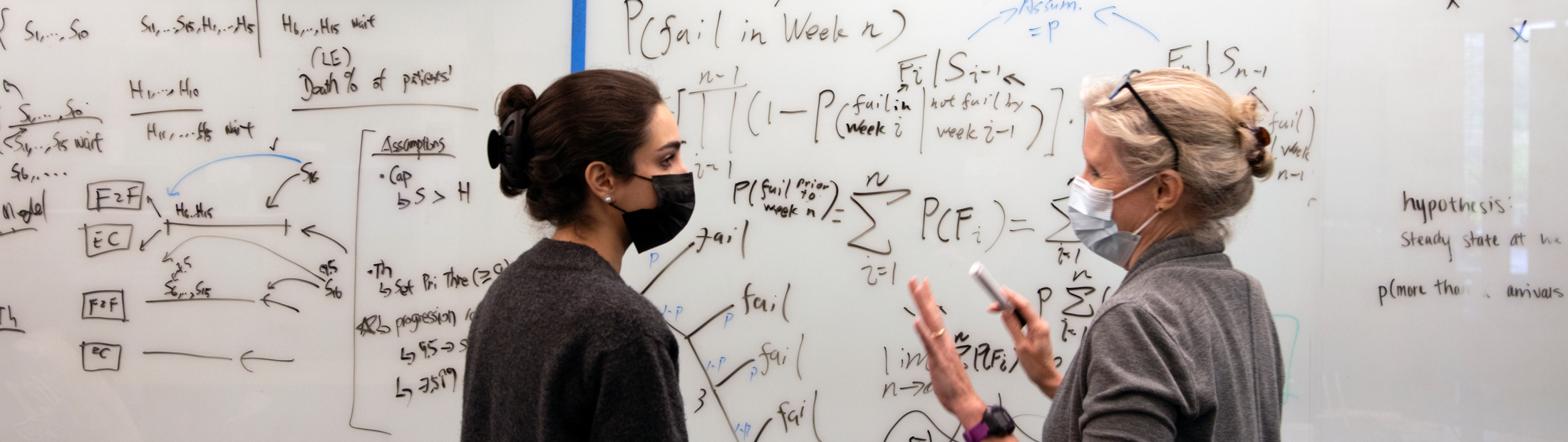

When CHEPS was formed, Cohn says she was thinking in terms of, “How can we train engineers to work in a healthcare setting?” In airlines and automotive projects, Cohn had worked almost exclusively with other engineers—speaking the same language and approaching problems from a similar perspective—while in healthcare they were mostly speaking with practitioners. “So the approach shifted to, ‘How can we train engineers and clinicians to work together?’ Which includes… also teaching doctors, nurses, and others about a systems- based, data-driven, engineering approach.”

And getting everyone speaking the same language.

“At APL, we recognize the program that Amy has built, and the work and the folks at CHEPS,” Richardson says. “We’ve recruited many, and they all do so well in terms of the technical work, but also in communicating it not just to engineers but also to physicians and others who might not be experts.

“It’s hard to find someone like that, but Amy breeds them.”

Students affectionately refer to each other as “CHEPSters.” They sincerely call CHEPS a “family”—while also acknowledging the cliché. Yet in some cases it’s actually family.

Nina Scheinberg and Mark Grum met while working together in 2014 on a surgical instrument-processing project. They were good friends then, but when they saw each other at the annual CHEPS reunion in 2017, a romance was kindled—and they were wed this August.

While many CHEPS students are from within IOE and computer science, others hail from myriad other departments.

Scheinberg and Grum are not the only couple to have met at CHEPS. “CHEPSters used to joke about the ‘Cohnmances’ that formed in the office,” Nina says. “Amy’s a great boss, and an incredible person—and she’s apparently also a great matchmaker.”

“I was going to say I should get a finder’s fee but I actually do,” Cohn says. “I get to go to all the weddings—and I have a blast!”

Kim speaks passionately about Cohn’s commitment to and care of her students. “We care about the whole of you. Not just your work, not just you as an engineer, but the totality of you,” Kim says.

Cohn is the second of three daughters born to a mother who was in a PhD program in physics in the 1960s, and who later took a computing job in the earliest days of standard use computers.

“So I certainly grew up in an environment where, at a very early age, the notion of doing something that wasn’t broadly represented was present for me,” Cohn says. “And I think perhaps having been in many cases the odd man out in the room, I’m attuned to who may be feeling on the outs, and how do you engage people and create a safe space.”

“It’s not uncommon for me to think, especially as my own boys have gotten older, ‘What would I as a parent want in that situation for my child?’”

The toddler that Cohn and her husband toted with them from Massachusetts to Michigan back in 2002 is now the older of Cohn’s two sons. He graduated in April with U-M undergraduate degrees in both mathematics and computer science and began his PhD program at MIT this September.

“It’s possible we are one of the first cases of a female PhD alum giving birth to a child while she was a student at MIT also sending that child back to MIT for a PhD,” Cohn says. “Because there weren’t very many of us.”

Cohn felt heartened that during the pandemic, the CHEPS experience—not just its projects and their impacts, but its sense of community—seemed a source of strength and comfort to students.

“In particular the last couple of years, the things that I have observed undergrads trying to experience… to be living away from your family… and going through layers upon layers of racial and Covid and gun issues,” Cohn says.

“You cannot be around that and not be empathetic if you want to educate. If our students aren’t safe and well, why are we even bothering with teaching?”

Preeti Malani—a Professor of Medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases who advised the U-M president on matters of University-wide health and wellness when she was Chief Health Officer—first met Cohn when Cohn was part of the original leadership team at the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation (IHPI), a consortium of multidisciplinary U-M experts convened to build upon and accelerate U-M healthcare policy.

Malani is aware of Cohn’s wellness work—including in its most formal sense, as part of the Rackham Graduate School Mental-Health Task Force created in 2019. But she also knows that Cohn is “all hands on deck with her students” because Malani’s son—a recent IOE graduate and former CHEPSter—has first-hand insight into “how much she invests in her students, really thinks very broadly about their education, their connection, their well-being in every aspect.”

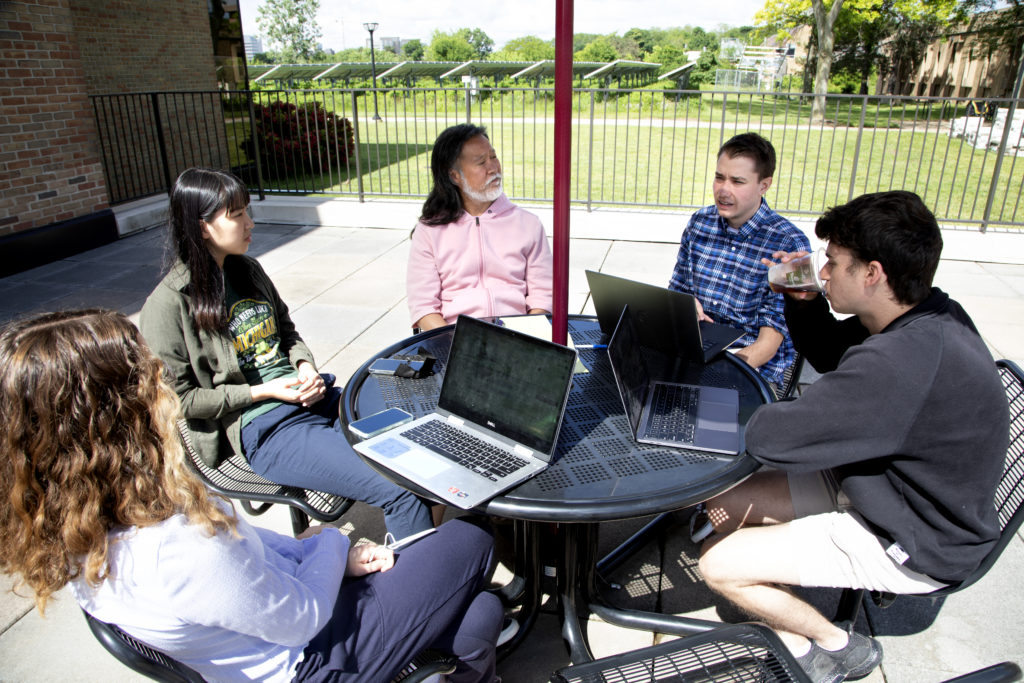

Cohn got directly and immediately involved—“on March 17 or 18”—in some of the most urgent problems of the pandemic: a dearth of masks, shutting down surgical and procedural suites, caring for infected patients, needing to test. Cohn was part of a “command center” at Michigan Medicine, serving as Michigan Engineering’s liaison, and a member of a campus-wide Covid response committee that was “very much in the thick of things.”

Cohn—naturally empathetic and collaborative, with a network-centric type of brain—found herself in exactly the right place at precisely the right time. Her School of Public Health appointment gave her access to that school’s resources, and her prior leadership role at IHPI—during which she developed relationships, domain knowledge, and connections—put her in a position to be constantly saying, “I know a person we should get looped in. We should call this person, who has a very disparate kind of background.”

“A lot of what the last couple of years have been, frankly, is being a coordinator,” Cohn says.

But of course it has been much more than that. Every aspect of Cohn’s career was coalescing, crying out for her particular brand of relationship-building in a crisis, and of finding solutions to healthcare system problems by leveraging students, and their experiential learning experiences, as an underutilized asset and an untapped resource. It was also an opportunity, Cohn says, to see “where the value of our work is in a very practical sense.”

By early April 2020, Cohn and others were already providing direct assistance to Michigan Medicine workers whose lives had been upended overnight through a website that paired them with volunteers willing to provide basic yet critical needs such as child care, grocery shopping, tutoring, and dog walking.

At the time, Cohn called the site “certainly nothing fancy.” But it was important to develop a means of supporting “colleagues who are putting themselves on the front lines in ways that most of us don’t have to” by simply “finding a group of people who were willing to roll up their sleeves and get the job done quickly.”

And now, more than two years later, this is still precisely how she describes that early period of the pandemic. “We got into the mode of not so much applying tools where they hadn’t been applied before, but—are you a really good problem-solver? Can you put out fires and just get stuff done?”

You solve problems differently from other people.”

CHEPS students worked on field hospital planning, infectious disease staffing, and planning for the rescheduling of patients whose non-emergent surgeries were delayed. Cohn’s work on saliva assay testing and vaccine clinics was less student-involved, primarily because of the incredible time demands to which Cohn would not subject her students.

Kim says some existing work continued, but much of it diminished, so as issues came up, “Amy would ad hoc just throw students out there. We were forming new project teams on the fly and we would just put and pull students on and off those projects very quickly.

“I think that was very impressive to Michigan Medicine—that with these engineering tools we could pivot very quickly, and have application across the block and in different arenas, and that Amy had a stable of very talented, very committed, very hard working students who got in there and got it done.”

Marshall Runge, CEO of Michigan Medicine, took notice. “You solve problems differently from other people,” he told Cohn.

Cohn had presented at a high-level roundtable hosted by Runge— discussing the types of problems CHEPS solves, the tools it uses, the way students are engaged—and Runge was extremely enthusiastic.

“We were largely doing one-off projects where one person found me for help with a project, and then another, but there was no real prioritization other than whether it seemed like a problem that would be a good learning experience for students and would it have a positive impact on the health system,” Cohn says.

Runge focused on how to choose projects more thoughtfully, at an institutional level, and how to grow the relationship. They eventually created a new position—Chief Transformation Officer—tailored specifically to Cohn’s talents, effective as of the end of last year.

“What I’m finding most interesting,” says Cohn, “is figuring out how all the pieces fit together and recognizing where the connections are. There’s just this spider web—this rippling of the pond—where every decision has some connection to every other part of the system. And that’s how my brain works. That’s the work I do.

“I keep trying to get my head above Covid and it keeps sort of sucking us back in,” Cohn said recently. But as day-to-day Covid response requirements have eased, the goal has been to use this same, CHEPS-style approach to tackle larger systemic problems at Michigan Medicine—and to create solutions that last well beyond Covid.

One such project now underway concerns Michigan Medicine’s recently initiated “Care at Home” program, intended to provide hospital-level care at home through visiting nurses and remote monitoring. The goals are to increase patient capacity even as demand outstrips facility capacity—and to improve access to timely care without increasing the stress on providers.

Cohn and CHEPS student teams are joining meetings with leadership and clinical collaborators to investigate options for expanding enrollment and to help identify patients who can tolerate and would rather receive healthcare treatments at home than in hospital facilities. CHEPS students are observing the clinical environment, gathering data to build models and conduct analyses, and helping to pilot solutions.

“I used to think of CHEPS as a kind of Skunkworks—especially when we were uglier, and all of our furniture was hand-me-down, and we were just trying to figure out what we were doing from day to day,” Kim at CHEPS says. “But now, our graduates leave with maybe an IOE master’s degree and an MBA, and they’re consultants who go into various workplaces and solve problems. We’re kind of an in-house consulting firm that nobody knew of before.”

And “cheerleader” Kim thinks CHEPS is “just at the beginning. I think it’s going to be sky’s the limit. As they continue to identify areas to make things better, they’ll bring Amy on board.”

Kim also notes that “Amy is starting to dip into each group and conversation” where people are working separately on mental health and wellness at Michigan. There are, however, “so many bad habits that are already ingrained—too many emails, meetings, too many demands”—that “Amy and our teams won’t be able to come up with solutions right away.”

But they’ll keep working on it. Because that’s what CHEPSters do. And because the joyful, compassionate, indefatigable Amy Cohn will be guiding them.