Graphene-hBN breakthrough to spur new LEDs, quantum computing

Study uncovers first method for producing high-quality, wafer-scale hexagonal boron nitride.

Study uncovers first method for producing high-quality, wafer-scale hexagonal boron nitride.

EXPERTS:

In a discovery that could speed research into next-generation electronics and LED devices, a University of Michigan research team has developed the first reliable, scalable method for growing single layers of hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) on graphene. The process, which can produce large sheets of high-quality hBN with the widely used molecular-beam epitaxy process, is detailed in Advanced Materials.

Graphene-hBN structures can power LEDs that generate deep-UV light, which is impossible in today’s LEDs, explained Zetian Mi, a professor of electrical engineering and computer science at U-M and a corresponding author of the paper. Deep-UV LEDs could drive smaller size and greater efficiency in a variety of devices including lasers and air purifiers.

“The technology used to generate deep-UV light today is mercury-xenon lamps, which are hot, bulky, inefficient and contain toxic materials,” Mi said. “If we can generate that light with LEDs, we could see an efficiency revolution in UV devices similar to what we saw when LED light bulbs replaced incandescents.”

hBN is the world’s thinnest insulator, while graphene is the thinnest of a class of materials called “semimetals,” which have highly malleable electrical properties and are important for their role in computers and other electronics. Bonding hBN and graphene together in smooth, single-atom-thick layers unleashes a treasure trove of exotic properties. In addition to deep-UV LEDs, graphene-hBN structures could enable quantum computing devices, smaller and more efficient electronics and optoelectronics and a variety of other applications.

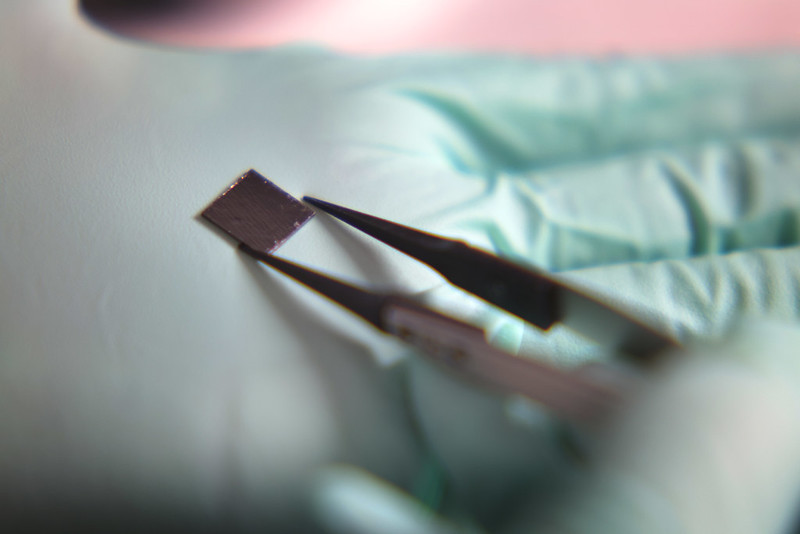

“Researchers have known about the properties of hBN for years, but in the past, the only way to get the thin sheets needed for research was to physically exfoliate them from a larger boron nitride crystal, which is labor-intensive and only yields tiny flakes of the material,” Mi said. “Our process can grow atomic-scale-thin sheets of essentially any size, which opens a lot of exciting new research possibilities.”

Because graphene and hBN are so thin, they can be used to build electronic devices that are much smaller and more energy-efficient than those available today. Layered structures of hBN and graphene can also exhibit exotic properties that could store information in quantum computing devices, like the ability to switch from a conductor to an insulator or support unusual electron spins.

If we can generate that light with LEDs, we could see an efficiency revolution in UV devices similar to what we saw when LED light bulbs replaced incandescents.”

Zetian Mi, professor of electrical engineering and computer science

While researchers have tried in the past to synthesize thin layers of hBN using methods like sputtering and chemical vapor deposition, they struggled to get the even, precisely ordered layers of atoms that are needed to bond correctly with the graphene layer.

“To get a useful product, you need consistent, ordered rows of hBN atoms that align with the graphene underneath, and previous efforts weren’t able to achieve that,” said Ping Wang, a postdoctoral researcher in electrical engineering and computer science. “Some of the hBN went down neatly, but many areas were disordered and randomly aligned.”

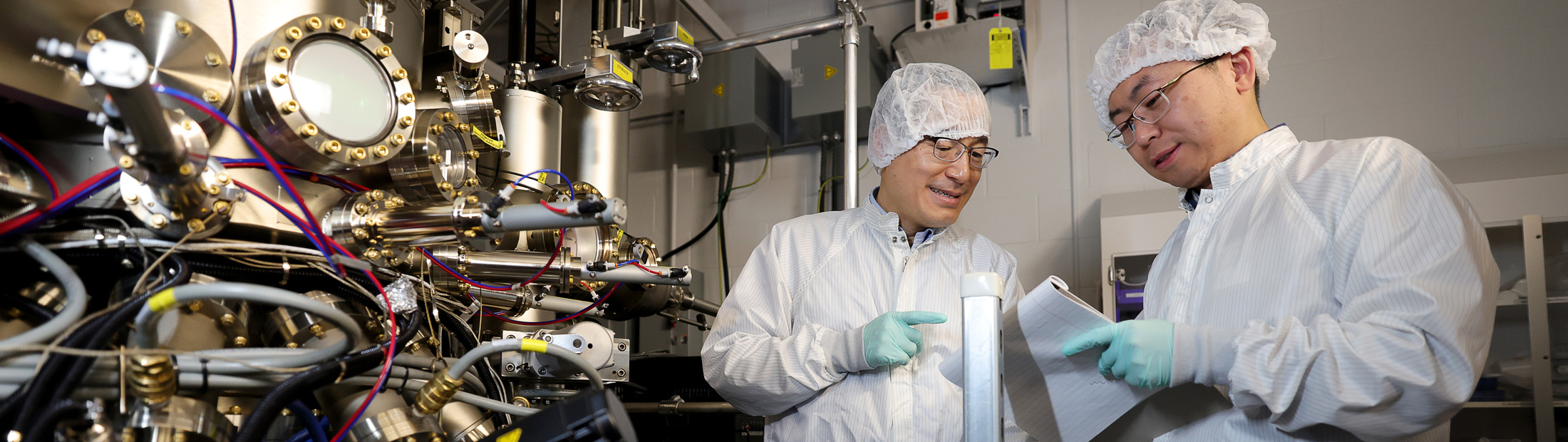

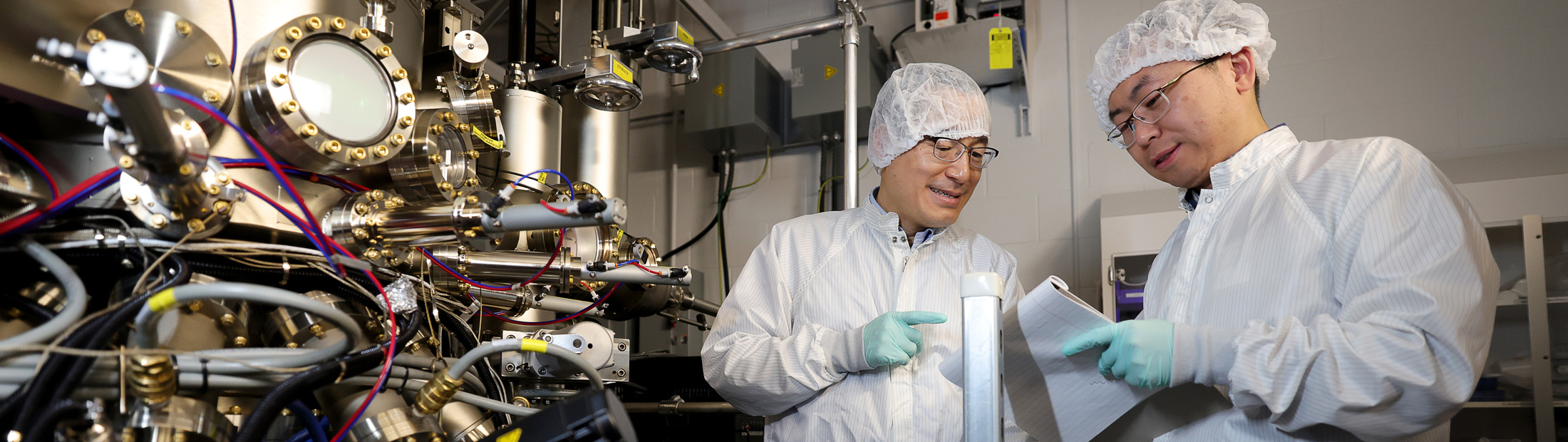

The team, made up of electrical engineering and computer science, materials science and engineering and physics researchers, discovered that neat rows of hBN are more stable at high temperature than the undesirable jagged formations. Armed with that knowledge, Wang began experimenting with molecular-beam epitaxy, an industrial process that amounts to spraying individual atoms onto a substrate.

Wang used a terraced graphene substrate—essentially an atomic-scale staircase—and heated it to around 1600 degrees Celsius before spraying on individual boron and active nitrogen atoms.The result far exceeded the team’s expectations, forming neatly ordered seams of hBN on the graphene’s terraced edges, which expanded into wide ribbons of material.

“Experimenting with large-amounts of pristine hBN was a distant dream for many years, but this discovery changes that,” Mi said. “This is a big step toward the commercialization of 2D quantum structures.”

This work would not have been possible without researchers from a variety of disciplines. Mi and his team, including Ping Wang, David Laleyan, Yuanpeng Wu, Ayush Pandey and Ding Wang developed the materials synthesis process and performed structural and optical studies.

For the mathematical theory that underpins some of the work, Mackillo Kira, a professor of electrical engineering and computer science at U-M, and his PhD students Woncheol Lee (electrical and computer engineering) and Qiannan Wen (applied physics), worked with Emmanouil Kioupakis, an associate professor of materials science and engineering professor at U-M, and Diana Y. Qiu, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering and materials science at Yale University.

Detailed structural and electrical characterization were performed by Jay Gupta, a professor of department of physics at Ohio State University, and his group members Joseph Corbett and William Koll, and by Robert Hovden and John Heron, assistant professors of materials science and engineering at U-M, and their group members Jiseok Gim and Nguyen M. Vu.

The project was conducted under the U-M College of Engineering Blue Sky Initiative, which supports high-risk, high-reward research that can lead to transformational change in areas like quantum engineering, carbon capture and reuse and next-generation drug development.

The research was supported by the Michigan Engineering Blue Sky Initiative, the Army Research Office (grant number (W911NF-17-1-0312) and the National Science Foundation (grant numbers DMR-1807984, DMR-2118809, and MPS-1936219), the U.S. Department of Energy (DE-AC02-05CH11231 and DE-SC0021965), and the W.M. Keck Foundation.