Solar storm: U-M model’s predictions ‘a remarkable achievement’

A space weather tool Michigan Engineers developed was used to produce animations that show predictions of how the recent storm would distort Earth’s magnetic field.

A space weather tool Michigan Engineers developed was used to produce animations that show predictions of how the recent storm would distort Earth’s magnetic field.

For the first time during a major solar storm, Michigan Engineer’s space weather modeling framework this week produced regional geospace forecasts. The forecasts, unique for each 350-square-mile plot of Earth, and up to 45 minutes lead time, are designed to help electric utilities and others prepare in time to limit consequences. Previously, it was impossible for scientists or forecasters to tell which areas of the Earth would be hit hardest.

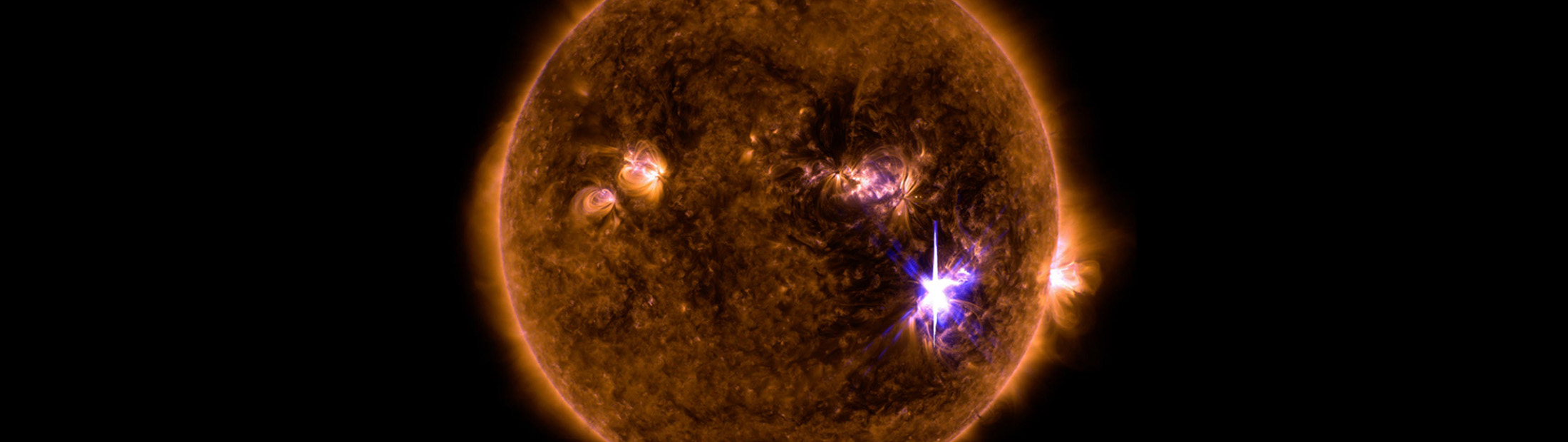

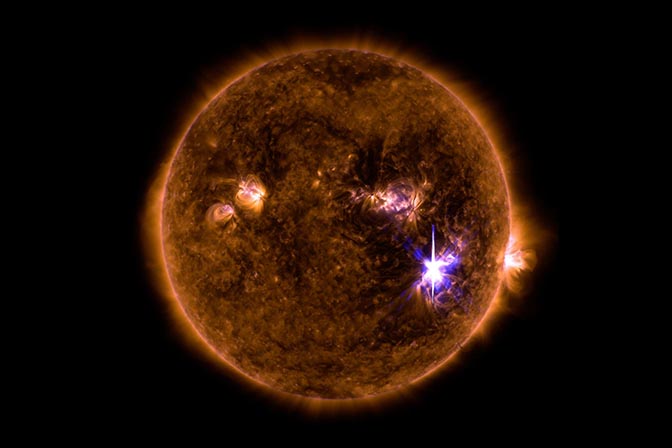

A severe solar storm struck the Earth this week, leading to an hour-long radio blackout on the daytime part of the planet.

The model is driven in part by solar wind data gathered upstream of Earth toward the sun by NOAA’s DSCOVR satellite.

“Using these data, the model was able to provide a very accurate prediction of the initiation and intensity of the storm with about 30 minutes lead time,” said Howard Singer, chief scientist at NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center. “This is a remarkable achievement and a tribute to the scientists at the University of Michigan who developed the model, as well as all the folks at NOAA who made it possible to transition this model into operations. The model prediction provided forecasters with accurate and useful guidance for SWPC products that are delivered to our customers.”

Solar storms are torrents of charged particles and electromagnetic fields from the sun that rattle the planet’s magnetic field. Major disturbances can send harmful current into power lines, hampering operations and putting expensive transformers at risk. They can also damage satellites.

Using the U-M model, the Space Weather Prediction Center published magnetic perturbation forecast maps for the globe, the U.S. and the polar regions.

“Power lines near the strongest distortions can be impacted, leading to power interruptions or even blackouts,” said Dan Welling, assistant research scientist in the U-M Department of Climate and Space Sciences and Engineering and one of the model’s developers. “Having these regional predictions before and during the storm can help power grid managers prepare.

“I’m very happy to say that the model did a great job predicting the storm’s dynamics. We nailed predictions of Kp and Dst — common indexes scientists use to measure storm strength.

The center is incorporating the model’s output into its global and local predictions.

“Officially, however, the model is in experimental mode, so it does not generate warnings in an automated fashion yet,” said Gabor Toth, research professor in the U-M Department of Climate and Space Sciences and Engineering and one of the model’s developers. “We hope that will become reality in the future.”

The U-M tool, in official use since October 2016, represents the first time a computer model based on a firm understanding of physics has overtaken simpler, statistics-based models to predict magnetic disturbances due to space weather. One of the problems with statistics-based models is that they can’t predict events outside their statistical comfort zones. So the strongest storms could be missed.

Extreme space weather can happen at any time, but historically the strongest storms tend to hit during the declining phase of the sun’s 22-year activity cycle. That’s the phase the sun is currently in. It’s expected to hit solar minimum by 2020.