A smarter way to design rocket engines that don’t blow up

Researchers seek to understand a problem that has haunted the space program since Apollo: a flame inside the rocket engine that literally spirals out of control.

Researchers seek to understand a problem that has haunted the space program since Apollo: a flame inside the rocket engine that literally spirals out of control.

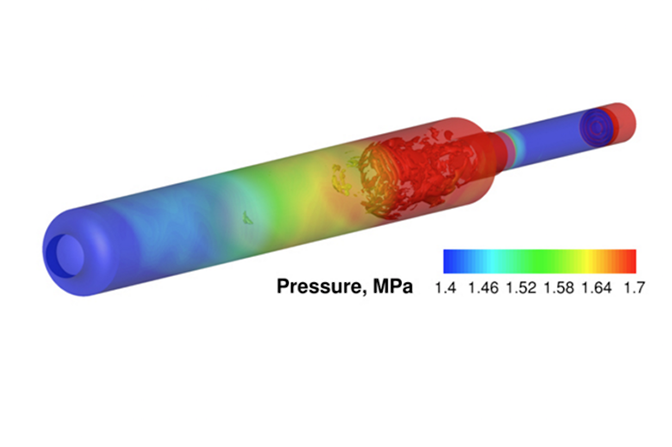

The problem has haunted the space program since Apollo: the flame inside the rocket engine literally spirals out of control, producing forces that can cause the engine to explode. It’s one of the reasons why some U.S. military and commercial satellite launches rely on Russian rocket engines to take them to space.

Now, a team of researchers at the University of Michigan, Purdue University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology will try to get to the root cause with a $4.2 million grant from the Air Force Research Laboratories and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research.

New rocket designs needs new rocket engines, but combustion instabilities make it difficult to develop rocket engines without blowing up some prototypes along the way. These wild flames go back to the prototype for the rocket that took astronauts to the moon. That engine exploded during a test.

The engineers discovered that the flame was driving a spiral current that resonated inside the engine, growing strong enough to blow the engine apart. But the physics of the current was so complicated that they couldn’t entirely work out what was happening.

To illustrate the problem’s pedigree, Karthik Duraisamy, an assistant professor of aerospace engineering at U-M, and director of the new Center of Excellence on Rocket Combustor Dynamics, showed a clip from the the documentary “Moon Machines: The Saturn V Rocket.”

“Keep in mind that back in those days, we were designing rocket engines basically with slide rules,” says Sonny Morea, project leader on the engine for the Saturn V rocket.

The Saturn V engineers put extra metal plates inside the engine to damp out the oscillations, experimenting until they found the right configuration. This is how rocket engines are designed to this day, prolonging development time and causing cost overruns.

“Unfortunately, even with the tremendous advances in computing over the past 50 years, we are still not in a situation to perform efficient simulations to help designers understand and avoid combustion instabilities,” said Duraisamy.

He plans to get to the bottom of the problem by using mathematical techniques that can process a large cache of simulation data to extract information and create efficient physical models. At the heart of the project are algorithms and facilities developed at U-M, specifically meant for this purpose. The researchers will combine the data with physical models of the flow and flames inside the engine, testing and refining the models while they run.

Purdue has been building and testing rocket engines for decades. Propulsion researchers there, led by William Anderson, a professor of aeronautics and astronautics, will provide their expertise of the physics inside rocket engines and combustors. Researchers at MIT, led by Karen Willcox, co-director of the MIT Center for Computational Engineering, will consult on simplifying the computational models so that it is feasible to run them in a reasonable amount of time. Data sources include extensive experiments and simulations performed at Purdue and by the Air Force.

“An accurate predictive model of combustion instability in liquid rocket engines will be an extremely useful tool in support of Blue Origin’s American engine development programs,” Robert Meyerson, president of private spaceflight services company Blue Origin, wrote in support for this project.

“Blue Origin will be interested in technical information exchange throughout the effort, and can provide practical advice on key problem areas and participate as a field tester of the predictive tools.”