Moving at the speed of need

How bold moves in COVID-19’s early days are powering new possibilities five years later.

They say necessity is the mother of invention. But fear deserves some credit too.

Introduction

Wastewater monitoring goes prime-time

Downloadable disease detection

A revolutionary technology looks for its niche

Could plasma ward off the next pandemic?

What we are (and aren’t) doing to strengthen PPE supply chains

COVID-19’s official United States arrival, in Washington state on January 20, 2020, jolted the nation into high alert. Escalating death tolls, mixed messaging from government officials and uncertain paths of transmission raised all kinds of questions. Each one potentially had life-or-death repercussions during the pandemic, a slow-motion catastrophe that claimed millions of lives around the globe.

On college campuses, it was an all-hands-on-deck moment as researchers scrambled to use or adapt their expertise to find answers. Late in 2019, Jesse Capecelatro, a University of Michigan assistant professor of mechanical engineering and aerospace engineering, was among the first. He had been studying how spacecraft thrusters disturb dust on planet surfaces and how those particle flows impact landing. A month into the pandemic, he realized that his research was urgently needed here on Earth–to predict how COVID-19 aerosols could spread in crowded areas like buildings and buses.

“I remember everything going into hyperdrive,” Capecelatro said. “Everything else in my life came to a halt. I found myself working alongside colleagues I’d wanted to work with since joining U-M in 2016. We were taking measurements and analyzing them to inform decisions on timescales of days and weeks, rather than the years that typical academic research takes.”

His research led to changes, like shorter bus routes and building occupancy guidelines, that helped keep U-M’s campus safe during the pandemic.

Early on, U-M leaders brought engineers into emergency discussions to identify dangers and protect public health. That led to a slew of research efforts that included everything from how aerosols move through dental offices to whether N95 masks could be disinfected and reused.

Five years later, the ripple effects of COVID-19 are still visible. Some led directly to new technologies that are still in use today. Others have morphed into new ideas and products beyond their initial spaces. And still others have come to a halt altogether.

Here, we look at the fates of four of those projects a half-decade after they started.

Radical. Until it wasn’t.

“Niche.” Or, perhaps, a pursuit “without a broad application.”

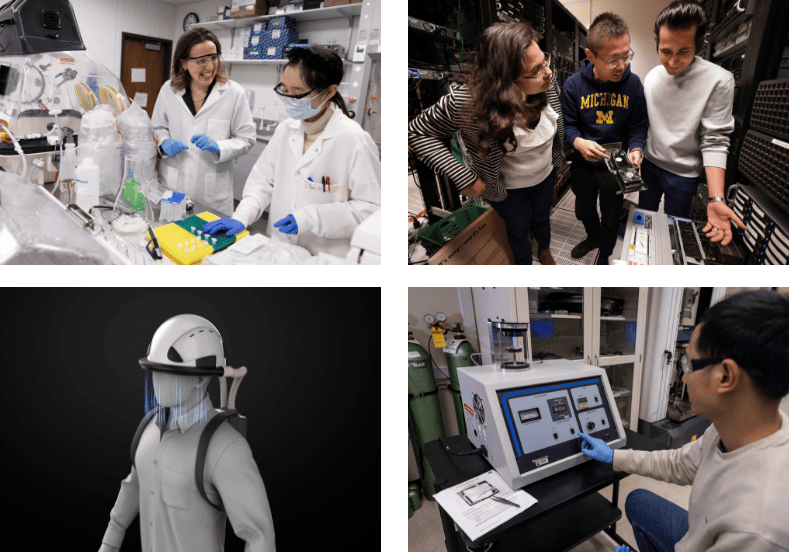

Krista Wigginton is certain that’s how many peers viewed her wastewater research in the years before the pandemic. In 2012, when Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) was in the public’s consciousness, she wrote a successful NSF career proposal on identifying respiratory viruses in wastewater systems. Wigginton is a U-M professor of civil and environmental engineering.

Wastewater-based epidemiology had been used for decades as a means of tracking polio, but its usage beyond that was limited. The research topic never quite seemed to take hold prior to COVID-19, largely because it fell between the tracks of federal agency funding.

“The federal government was just not willing to put much into it,” Wigginton said. “I think they were hesitant to buy into something that was so radical at the time.”

Wigginton and her research team persisted. They spent years developing methods for measuring coronaviruses in wastewater. That research led to papers that analyzed how long the viruses could remain infectious. Would they survive long enough to reach treatment plants, streams or other bodies of water? How did they respond to different environmental conditions like sunlight or ultraviolet light?

“One thing that we saw early on was that these are pretty wimpy viruses,” Wigginton said. “They are inactivated very quickly in normal conditions in water.”

The good news was that the fragility of the viruses prevented them from spreading by way of water and sewage systems. But it also meant that tracking them could be a challenge.

“Unlike human DNA samples in wastewater, concentrations of these respiratory pathogens are really low,” Wigginton said. “We’re talking a few organisms per liter or even less. And you can’t simply measure the wastewater directly because our tools use samples that are only tens or hundreds of microliters. So with that huge volume, you have to select the organisms you want to target and concentrate them in order for them to be detected.”

In 2016, she and three other civil and environmental engineering researchers published a paper titled “Survivability, Partitioning and Recovery of Enveloped Viruses in Untreated Municipal Wastewater”—essentially a breakdown of how coronaviruses and similar viruses behave in wastewater systems.

In the three years following its publication, other researchers cited the paper only 20 times—hardly a blip on the radar. But even though many researchers considered her work to be too niche for prime time, she had a hunch that it was important.

“My thought was that if we ever had something huge hit, like a pandemic, we needed to be equipped to understand how respiratory viruses behave in terms of our wastewater and the spread of disease.”

Then, something huge hit. COVID-19’s arrival sent public health officials scrambling for ways to monitor its spread.

“I thought, ‘We know how to do this!’” she said. “Before, we were looking at it as a means of determining what risk they were posing to the community…It was just a tweak of the same data, the same methods, but looking at it from a different perspective.

“We looked at wastewater, not to understand how much treatment would be needed, but to monitor to understand what was happening in our community.”

Wigginton, together with Stanford professor Alexandria Boehm, applied for a $200,000 Rapid Response Research grant at NSF to start measuring the pathogens in the wastewater at Stanford and, with the pandemic underway, the federal agency approved it.

What began from that partnership has grown into WastewaterSCAN—a national monitoring program for infectious diseases in wastewater. It’s currently operating in 40 states, scanning for roughly a dozen pathogens, including avian influenza.

“These are pretty wimpy viruses”

In July of 2024, WastewaterSCAN helped identify a spike in COVID-19 in the San Francisco Bay Area, noting that it had reached levels that equaled the previous winter’s peak.

Two months later, WastewaterSCAN alerted U.S. public health officials to an alarming increase in the presence of the D68 enterovirus, which can cause acute flaccid myelitis (AFM). AFM is a polio-like disease that can cause paralysis in children. And in January of 2025, WastewaterSCAN alerted officials in Lincoln, Neb. to the presence of H5 avian influenza.

A founding member of WastewaterSCAN, Wigginton eventually chose to return to U-M in order to build the Wigginton-Eisenberg Laboratory into a leader in wastewater-based epidemiology. It has also enabled her to get back to what she feels she does best.

“I like fundamental research that explains, that can help drive us through the next big problem,” she said. “I don’t want to deal with different sectors of government and different organizations trying to get a piece of the pie. I’d rather head back to the lab and see which questions we need to answer now.”

Wigginton is an advocate for the growing field of wastewater-based epidemiology. She runs a U-M-based wastewater monitoring program in Ann Arbor that provides data to the University, the State of Michigan and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And she has served as a panel member for the National Academies on wastewater-based infectious disease surveillance, helping to determine how the U.S. can support the technology going forward.

And that paper that garnered only 20 citations in three years before COVID-19? It has been cited nearly 600 times since.

Tracking disease with a download

In the early days of the pandemic, the COVID-19 virus was something of a mystery. The mechanisms behind its spread were not well understood, largely because the home tests that we’re familiar with today were not yet widely available.

“One of the reasons why COVID started spreading as much as it did was because of our inability to detect and contain it early on,” said Satish Narayanasamy, a U-M professor of computer science and engineering.

The pandemic made it disturbingly clear that fast disease detection wasn’t a strong suit in the U.S. or elsewhere. U.S. health officials did, however, have the entire genomic sequence of the COVID-19 virus as early as January of 2020. It was a clue that would fuel a new avenue of research, both during and after the pandemic.

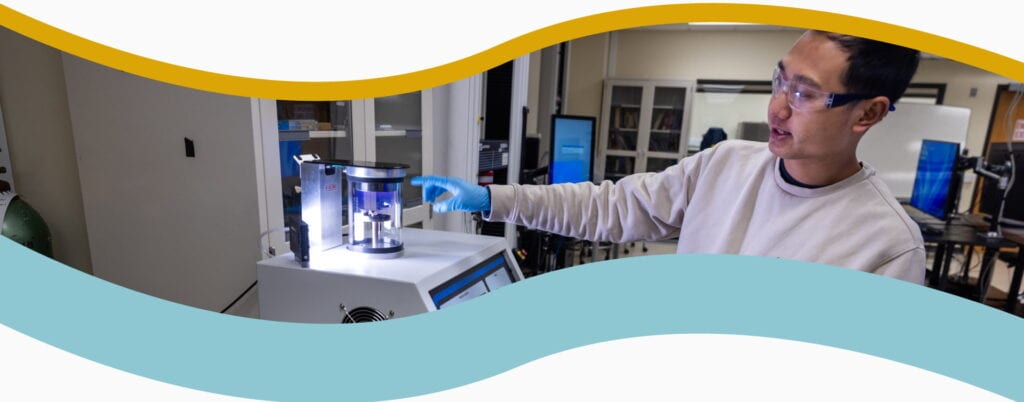

Five years before COVID-19 arrived, Narayanasamy was working with Reetuparna Das, a U-M associate professor of computer science and engineering, to design specialized, task-specific computer chips. While the chip industry was focused mainly on machine learning, Narayanasamy and Das had begun to look for other areas where there was a need for heavy computing power.

Genome sequencing was one such domain—in just two decades, the cost of sequencing a human genome had plummeted from $100 million to $1,000. But sequencing a whole genome still took days. Collaborating with David Blaauw, the Kensall D. Wise Collegiate Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at U-M, Das and Narayansamy worked to build specialized hardware that could slash gene sequencing time to minutes.

When the pandemic hit, the idea suddenly seemed like a revelation. What if they could build a chip to analyze the output of a portable genome sequencer in real time? This could enable doctors to detect COVID-19 or any other virus or bacteria—even those for which tests did not yet exist.

“I thought ‘We know how to do this!’”

Working with Robert Dickson, the Galen B. Toews Legacy Professor of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine at the U-M Medical School, Das and Narayanasamy envisioned a portable electronic device that could download the digital genomic signature of a new pathogen in order to detect it in saliva or blood. Widely deployed in doctors’ offices, the devices could make it possible to track even the newest pathogens.

They were successful in developing specialized chips that can sequence an entire genome in less than 30 minutes. But they were unable to cut their costs to a level that would make them practical for widespread use.

But Narayanasamy and Das have not given up on the idea that computing power can be used to fight pathogens. They’ve ridden the momentum from their COVID-era research into a different clinical space called “intraoperative cancer diagnosis.”

Das, Narayanasamy and their colleagues are working on technology that could sequence biopsy tissue much more quickly—during the biopsy procedure itself–and take action immediately. This could dramatically reduce treatment time and the need for additional surgical procedures.

The research began in 2020, when the pair was working with a physician who treats pediatric patients with brain tumors. Genomic sequencing can detect mutations in cancer cells, helping clinicians personalize treatments for individual patients. But sequencing currently takes days or weeks, creating a bottleneck in the treatment process that makes it more difficult to get ahead of the disease.

In a 2022 research paper, they demonstrated the ability to confirm cancer mutation from tumor tissue in less than 30 minutes. They’re currently working with chip makers Nvidia and AMD to bring down the cost of their technology.

“With specialized chips you can often get a ten thousand-fold increase in efficiency,” Das said. “But it takes significant labor to build such chips. So the question is: what are the killer applications that require that level of efficiency. We believe portable sequencing and intraoperative diagnoses are worthy of investing that level of effort.”

“We continue to look for more such applications in the medical domain.”

An invisible mask

It’s February 7, 2025, a cold Friday morning in Michigan, and Herek Clack is hitting the road. The U-M professor of civil and environmental engineering is headed two hours north of Ann Arbor, to Mt. Pleasant, where he’ll attend the Great Lakes Regional Dairy Conference.

Once there, he’ll shift from the role of researcher to entrepreneur—demonstrating the non-thermal plasma technology that he believes will one day protect agriculture workers (and, possibly, the rest of us) from airborne pathogens like avian influenza. Promotion is a bit of a change of pace for someone who does not have a personal account on any social media platform other than LinkedIn.

“It’s never my first choice, but I can do it and do it pretty well when needed,” said Clack, who has developed a familiarity with the agricultural industry over the past decade.

Before COVID-19, Clack’s research focused on preventing the spread of airborne viruses among agricultural livestock through the use of cold plasma. A plasma is a state of matter containing a significant portion of charged atoms, molecules, ions and molecular fragments. An easier way to understand it is to consider the plasma that humans are perhaps most familiar with: fire. Cold plasma has similar germ-killing properties to fire, but without the heat.

Since the start of the 21st century, outbreaks of foot-and-mouth disease, avian influenza and porcine epidemic diarrhea have grabbed headlines in the U.S., costing the animal agriculture industry billions annually. Pre-COVID-19, Clack saw non-thermal plasma as a means of preventing the spread of such threats among livestock in enclosed environments. Early in 2019, you could find him doing field tests at a pig farm near Ann Arbor, hoping to demonstrate cold plasma’s effectiveness in preventing the airborne transmission of viruses in animal populations.

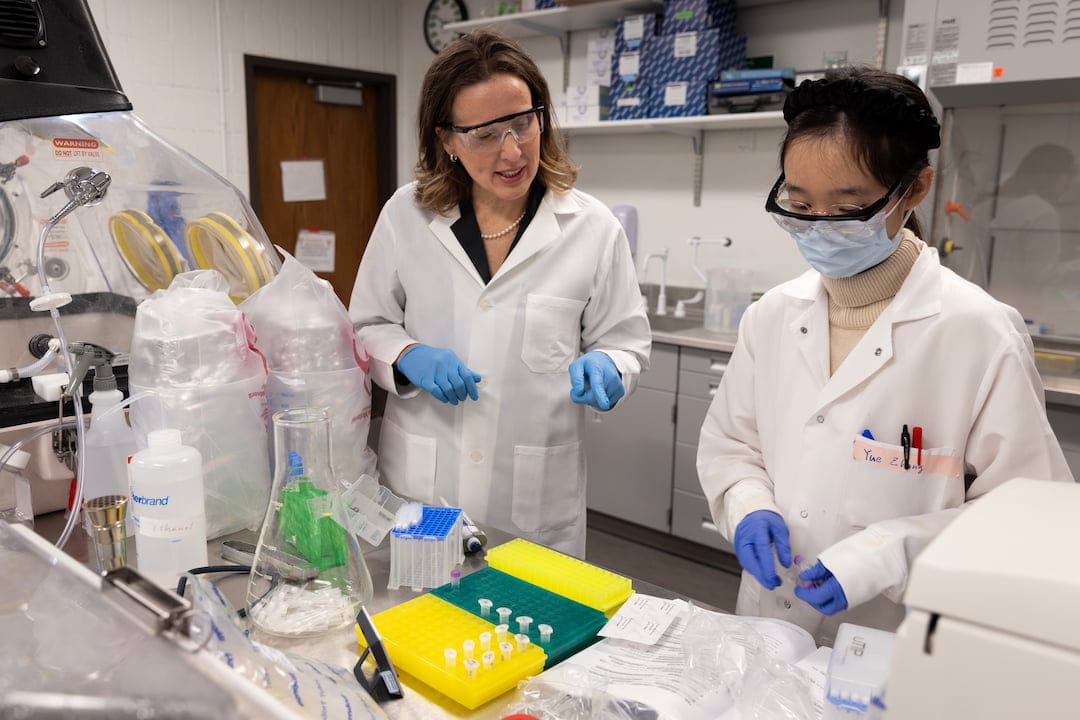

The plasma reactor Clack developed directs an air flow through a non-thermal plasma generated within a bed of borosilicate glass beads. Any viruses are inactivated as they pass through the spaces between the beads.

“In those void spaces, you’re initiating microscopic sparks,” Clack said. “By passing through the packed bed, pathogens in the air are oxidized by unstable atoms called radicals. What’s left is a virus that has diminished ability to infect cells.”

The results were promising, with experiments showing that a plasma reactor connected to an agricultural enclosure’s ventilation system could inactivate or remove 99.9% of a test virus. But by late 2019, the work had slowed somewhat when tariffs on pork exports hit pork producers’ bottom lines and Clack was forced to look for a new microbiology collaborator.

The research took a major turn when COVID-19 entered the picture in 2020. U-M officials had invited faculty to submit ideas for pandemic-related research projects. Clack submitted two cold plasma proposals in conjunction with Taza Aya, a company he had co-founded 5 years earlier.

The first of these was a tabletop version of the cold plasma air curtain—something that might have been used to protect people in small areas, such as a group of people eating at a table. The second concept used ultraviolet lights placed on ceiling fans. Neither proposal was accepted, but two key developments would help Taza Aya narrow its focus.

The first came in October 2020, when Taza Aya was named a $200,000 awardee in the Invisible Shield QuickFire Challenge—a competition created by Johnson & Johnson Innovation in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The goal was to create “potential solutions that repel and protect against airborne viruses while integrating seamlessly into everyday life.”

Clack was also called on by U-M to solve COVID-related problems, working to determine whether N95 masks could be disinfected and used multiple times. The more time he spent around the masks, the more he came to realize that they might not be the best solution for every situation. In noisy factory environments, for example, masks can fog up safety glasses and inhibit communication. He began to wonder if his cold plasma technology could hold the answer.

His persistence paid off when, in February 2023, the USDA’s National Institute for Food and Agriculture awarded Taza Aya $1 million to develop personal respiratory protection from airborne pathogens for meat and poultry processing workers that didn’t require the use of traditional face masks.

“I remember everything going into hyperdrive”

Clack set out to shrink the technology into something wearable and, a year later, Taza Aya’s team had a new prototype. Their Worker Wearable Protection device creates an air curtain, disinfected by a miniaturized plasma module, that shoots down from the brim of a hard hat. Testing has shown that it prevents 99.8% of aerosols from reaching the wearer’s breathing zone.

The prototype used a backpack, weighing roughly 10 pounds, that housed the non-thermal plasma module, air handler, electronics and the unit’s battery pack. Over several months, Clack conducted user experience testing with workers at multiple plants owned by the company Michigan Turkey Producers.

Workers had suggested they could live with a shorter battery life in exchange for reduced weight, and a beta prototype that incorporated that feedback and other improvements arrived at Taza Aya in December 2024. The new model is more than 30% lighter and still provides more than 7 hours of battery life.

“We also have the ability to manipulate the plasma in a way we couldn’t before,” Clack said. “We can increase or decrease the plasma intensity—allowing for different settings if you’re dealing with pathogens in mucus or saliva.”

It’s a technology with a great deal of promise, particularly with the threat of pathogens like avian influenza. Investment from the private sector has enabled Taza Aya to engage with a product development company that will sort out the most efficient and effective way to produce the product. By the end of the year, the company expects to build its first 500 devices, with most of those headed to Michigan Turkey Producers.

Disclosure: Clack and the University of Michigan have a financial interest in Taza Aya

A victory…and a warning

Early on in the pandemic, one of the toughest puzzles traced back to a simple fact: Chinese face masks are the most abundant on the planet and, in most cases, the cheapest. China controlled at least 72% of the U.S. N95 market at one point before the pandemic.

When COVID-19 first cropped up in late 2019, China responded to increasing case numbers by barring exports of the masks. This left the United States with few alternatives and created frightening shortages, including at Michigan Medicine’s facilities, where stocks of personal protective equipment (PPE) were being depleted at an alarming rate.

On March 13, 2020, as the last of U-M’s students and faculty were leaving North Campus to ride out the pandemic, Albert Shih was among a team of engineers and Michigan Medicine officials called to an emergency gathering to find solutions to the equipment shortage. It was more than just a health matter.

“The U.S. has and remains dangerously dependent on foreign countries for our supplies of critical life saving drugs and life saving equipment—masks, gloves, PPE and ventilators,” said Rep. Ann Eshoo (D-CA), then chair of the U.S. House Energy and Commerce Committee on Health, in May 2020. “As a result, we can’t treat our own people without relying on China and others to supply us. We can’t outfit our first responders, our hospital workers, our nurses, our doctors. We can’t care for our own nation in crisis. This surely is a national security issue.”

Shih was tasked with creating an on-campus N95 production facility to help bolster supplies for Michigan Medicine—a task right up his research alley.

“I don’t do software, but anything involving hardware, I’m good at that,” said Shih, a U-M professor of mechanical engineering and biomedical engineering. Given a specific task, he can envision and create the layout for a factory, understand what machines need to be procured and determine who needs to be hired to make it all work.

But N95 masks are not your typical widgets. In April 2020, Wired magazine laid out the complexities of the N95.

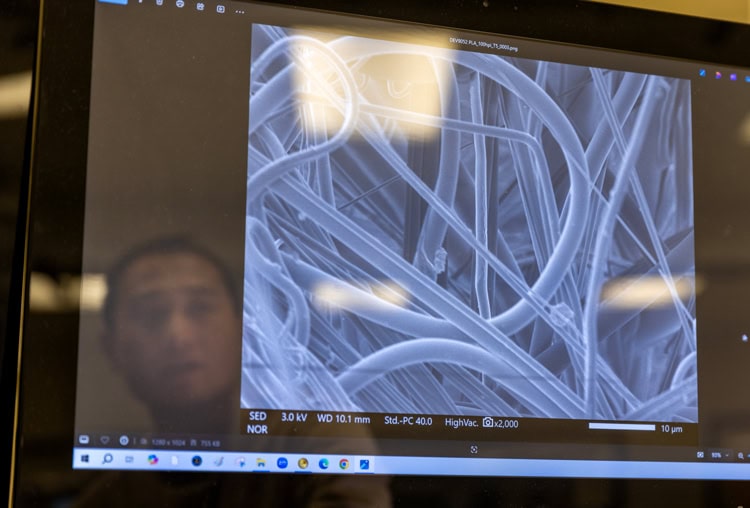

“They must sit snug enough to create a seal and fit to the individual’s face. The masks consist of two layers of cloth with a piece of melt-blown polypropylene in between. The polypropylene is extruded at extremely small diameters, then settles and cools in a random pattern. The fibers are electrically charged, attracting particles while allowing air to pass through.”

It was a relatively slow and difficult process for Shih and his team. Masks have five key parts: three filtering layers, a nose clip and loops that secure the mask to the head and ears. Each part needs a different machine for manufacturing, and a separate machine is used to put them together.

The melt-blown machine that produces the middle filtration layer and the final assembly machine are the most critical–and the most difficult to find. The team found a workaround by sourcing slightly different machines from U.S.-based companies and adapting them to manufacture the N95 masks.

Next, they integrated them into a production line that was small enough to fit inside a 40-foot trailer. When it was up and running on the Michigan Medicine campus, the system could turn out 80 N95 masks per minute—enough to alleviate the supply issues.

“Our defenses are down. Again.”

Post-COVID-19, Shih is working on another challenge related to N95 masks: their plastic construction, which is effective at filtering out pathogens but means that they can far outlast their useful life.

“Masks made of polypropylene can last for decades,” he said. “We’re hooked into this terrible/not terrible material that’s very effective, but not biodegradable.”

Shih is currently working with Ronald Larson, a U-M professor of mechanical and chemical engineering, and Brian Love, a U-M professor of materials science and engineering, researching new mask materials that will enable them to break down more quickly. Potential candidates include sugarcane and corn husks.

In a vacuum, we might call that a success story. Yet Shih would be the first to tell you this isn’t really that. Not even close. Concerns remain about what the U.S. is—or isn’t—doing, to be better prepared for future pandemics.

In 2021, Congress passed the Make PPE in America Act, which would have required “any contracts for the procurement of PPE entered into by the Department of Homeland Security, Veterans Affairs and Health and Human Services be for PPE, including the materials and components thereof, that is domestically grown reprocessed, reused or produced.”

But in 2021, China lifted its export ban and the country’s cheaper masks began flooding back into the market. Without the shadow of a public health emergency looming, mask production was no longer a priority. Many of the private U.S. companies that waded into the business have shut down or shifted their production to other, more in-demand products, making it difficult for agencies to comply.

“All the hospitals and government agencies and retailers that had been begging for American products suddenly said, ‘We’re good,’” Paul Hickey, co-founder of Utah-based mask supplier PuraVita Medical, told the New York Times in 2023.

Or, as Shih puts it: “Our defenses are down. Again.”

Why not simply stockpile millions of N95 masks to be ready for the next pandemic when it arrives? The electrical charge contained in the polypropylene fades over time, reducing their effectiveness—even if they’re simply in a box on a shelf somewhere, waiting to be used.

“If the U.S. government and healthcare providers can purchase PPE made domestically, that creates the foundation for a domestically competitive PPE manufacturing ecosystem,” Shih said. “The current situation is worrisome in case an erratic mutation influenza or bird flu threaten the general public again like in 2020.

“Our memories here are too short.”