Better wastewater treatment with biology

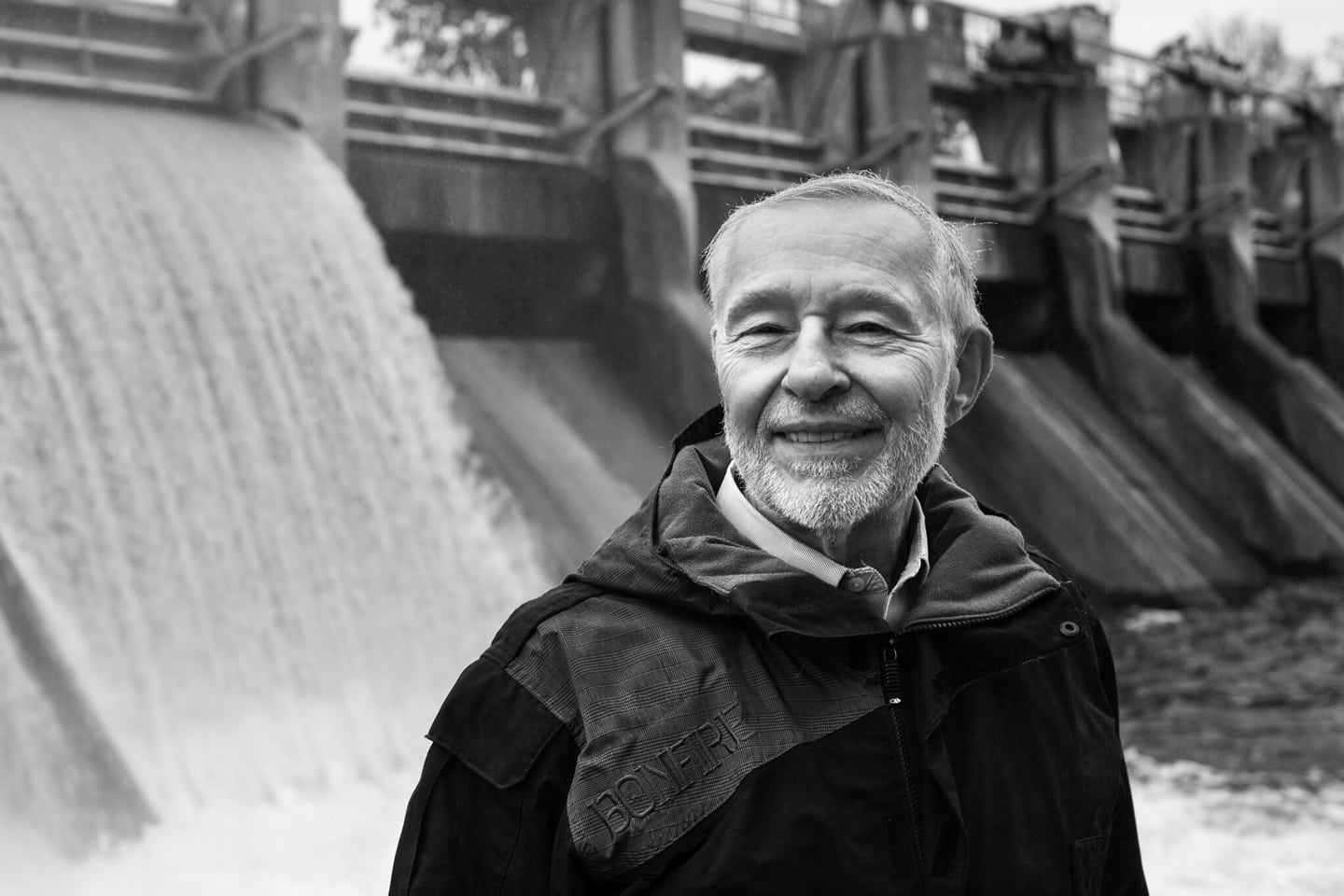

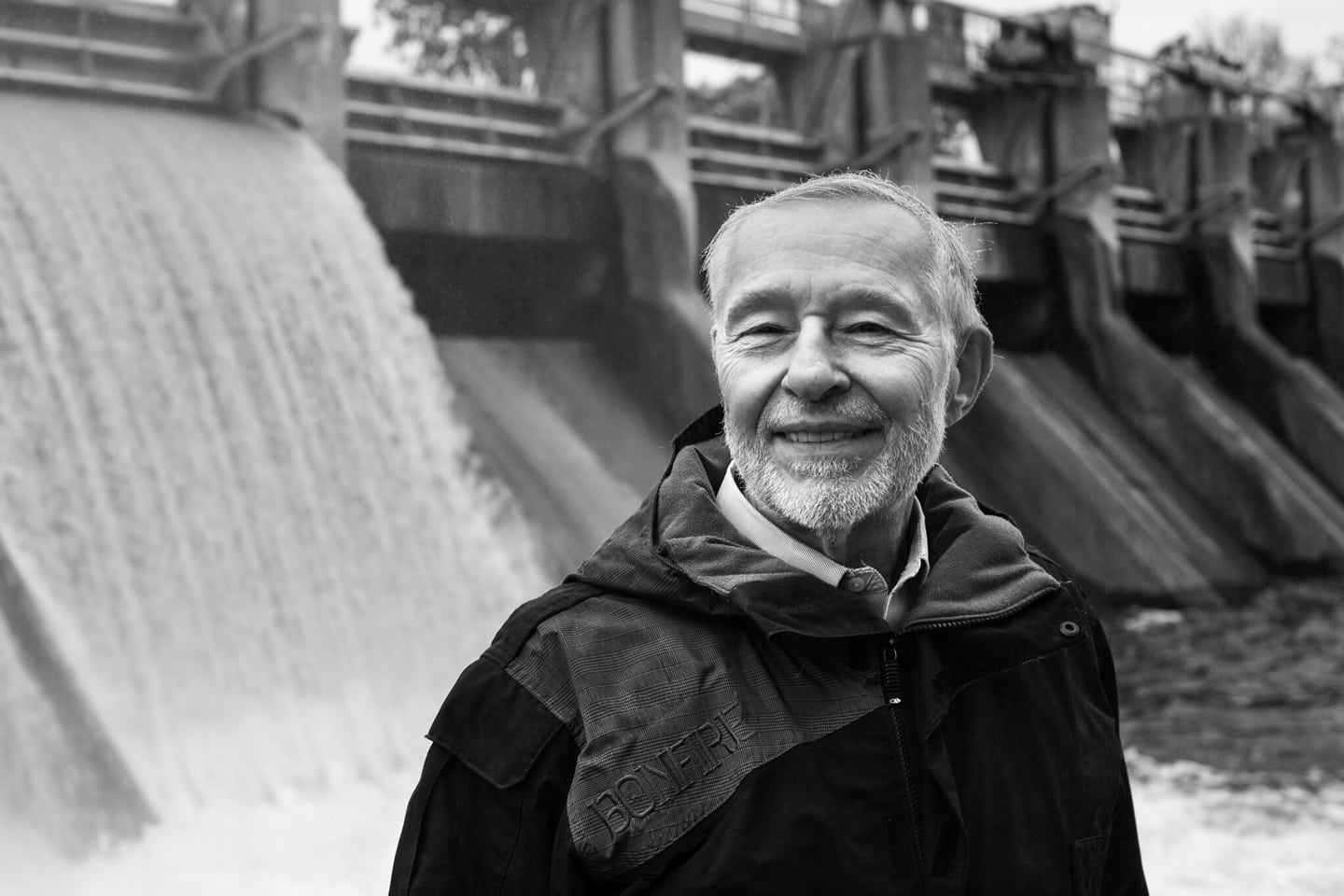

NAE profile: Glen Daigger, civil and environmental engineering

NAE profile: Glen Daigger, civil and environmental engineering

Get to know Michigan Engineering’s National Academy of Engineering members.

During his 35 years in industry, including as chief technology officer at CH2M Hill when it was the nation’s largest environmental engineering firm, Glen Daigger developed and implemented more sustainable, economical and effective wastewater treatment practices. Among his contributions is optimizing biological processes for removing nitrogen and phosphorus—nutrients that can lead to harmful algal blooms that threaten drinking water supplies and aquatic habitats. The nitrogen-removal technique he advanced requires 60% less energy than conventional approaches. For combining the theory and practice of wastewater-nutrient control and for improving the practice of environmental engineering worldwide, Daigger was elected to the National Academy of Engineering in 2003. View the NAE citation.

During his time at Michigan Engineering, he has expanded his research to include reuse of the phosphorus and nitrogen removed from wastewater in an effort to usher in a circular water economy.

Daigger’s work has informed our national wastewater treatment standards. Technologies he advanced have been widely adopted around the world, increasing wastewater treatment plants’ capacity and efficiency, helping to safeguard public health and aquatic ecosystems, and reducing both algal blooms and treatment costs. His textbooks are used across the country.

More on Glen Daigger

Daigger: “I grew up on a pig farm, so I always tell people I was meant to be in the waste management business. I grew up in the business end of the waste management business—the supply side. I got pretty good at managing biosolids.

We lived in Battleground, Indiana, about ten miles from Purdue’s campus. In my generation, farm kids went to places like Purdue—land grant universities. They taught agricultural arts and mechanical arts, which are agriculture and engineering. I was good at science and math. And if you were good at science and math, you went into engineering. So I followed that tradition. It was kind of that simple.

I was intellectually curious. The professors saw something and they offered an opportunity for graduate school. As I was approaching graduation, I used what today people would call exhaustive enumeration. This was 1978. There was no internet, no email. I sent out 100 resumes to anybody that I could. I had some academic interviews, some industrial interviews, and then some calls from consulting engineering firms. One was from CH2M Hill in Corvallis, Oregon. I had never been west of the Mississippi—if you live on a pig farm, you have to take care of the pigs. But I flew out and it just felt like the right place. So in June of 1979, I graduated, and my wife Patty and I packed up our little Honda Civic station wagon, drove out to Corvallis to be with CH2M Hill for two or three years and stayed for a little over 35.

Most of the time with CH2M Hill, if you asked my wife where my office was, she said it was on United Airlines. I pretty quickly started to work around the country and then probably a decade later started to become engaged internationally—so, Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, East Asia, a little bit of Europe, a little bit of the Middle East.

When I joined the firm, it was small and well-regarded but aspirational. I stayed the length of time I did because it was growing and as I needed the next opportunity for my own growth it was there.

Daigger: “I’ve learned that many engineers put themselves into a small box because they think that an engineering education provides them with technical knowledge, and that is what constitutes engineering. I had some great role models at CH2M Hill who taught me that what you really learn as an engineer is to look at a situation and form a functional model for it.

“And the reason functional is important is because you want to see why these things are happening. That tells you what you need to to change or work with others to change to get a different outcome. That’s the real skill of an engineer—to look at a situation and, some would say, frame it.

“You can apply this model to technical matters, to business, policy, leadership. And of course, as you move away from, or even in a technical setting, it’s also about people.

“I learned a piece of this pretty early in my career. In addition to engineering in the office, I was fortunate to be working with full scale treatment facilities. There was a core group of us doing this, and oftentimes troubleshooting. I was there because I was a recognized expert in biological treatment systems. People saw my role as helping to understand the microbiological problems, the problems in the tanks. Well, it didn’t take long to realize we also needed to understand the macrobiology, the biology standing around the tanks. And we don’t have a solution until we solve both. You apply the same basic engineering analysis and skills to figure out what’s going on and why.”

Daigger: “Become a t-shaped person. The t-shape is about in-depth knowledge and broad knowledge and an ability to collaborate. So learn your science and engineering. Build your detailed technical knowledge, but also your broad knowledge. It’s a blending of breadth and depth.

“While you’re at the university, take classes in the subjects that are harder to teach yourself. I worked with some great people. Most were engineers, but a lot of them had MBAs and so forth. So I’d ask them what to read. I gained a lot of business knowledge both by reading and working with them. You can teach yourself a lot of things. It’s hard to teach yourself physical chemistry, or subjects where you have to learn to look at something totally different. Know yourself and where you’ll need the most help, and take those classes.

“Look for opportunities to develop what is the real engineering skill, which is to look at a situation and formulate. You get those by being part of a team or in clubs, and interacting with people.”

Daigger: “In terms of a challenge, for decades the water profession has been comfortable with people getting the water service they need without understanding how that happens. But water is essential. For folks to not be aware of how it gets to them is a mistake, and it’s one of the reasons we have aging infrastructure. People don’t appreciate it. The profession is trying to change that, but it’s a big hole to dig out of.

And then the water management issues we face as a society today will certainly challenge water professionals, but there are some emerging opportunities.

Water stress is two things: droughts and floods—not enough water and too much water. We actually conceptually and demonstratively have the solution to droughts. So, the amount of water we use, coupled with climate change, is negatively impacting the natural water supply in terms of surface water and groundwater. But we’re doing a better job of conservation, which is the first thing, managing water capture. But, reuse is really the game changer. And then desalinization, or desal, can meet that last little gap.

The technology that we use for potable reuse and for desal is the same technology, but reuse is inherently much more energy efficient, which is important. Reuse has fewer environmental impacts than desalinization. It’s less expensive. A lot of places have learned that. It’s about getting the right combination of water supplies that function well over a range of conditions.

In terms of flooding, we’re not going to solve our wet water problems only with pipes. The Dutch have been the most proactive in doing this. They’ve got their pipes. They’ve got their dikes and so forth. But they have a phrase that they call “room for the river.” It means when we have these unusual events, they think about, “Where are we going to flood?” And then consciously manage where we flood. You protect public safety, you minimize the damage, and also you choose locations that can be restored back to their normal function the most easily.

Quotes edited from interview transcript between Glen Daigger and Marcin Szczcepanski.