$9.7M for tools to improve forecasts of harmful space weather

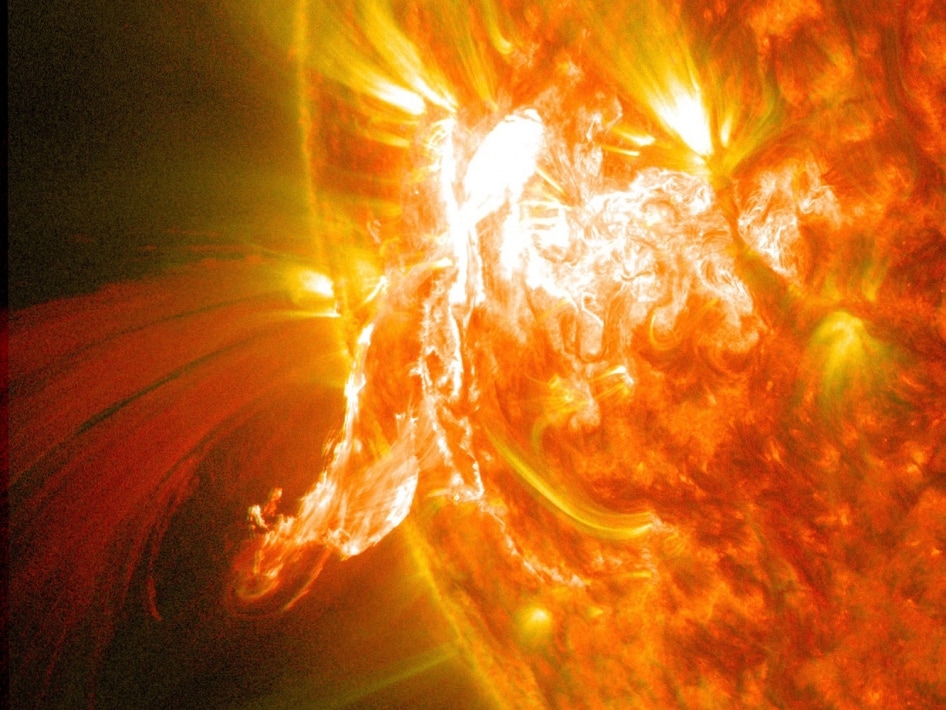

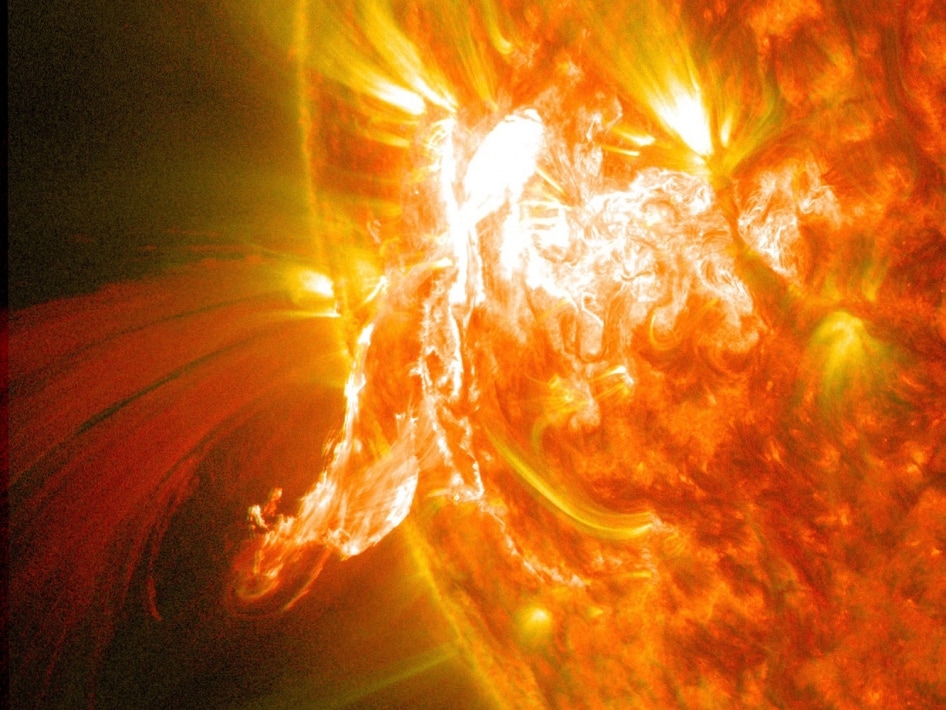

Better forecasting could protect astronauts and instruments from solar eruptions that release damaging, high-energy particles.

Better forecasting could protect astronauts and instruments from solar eruptions that release damaging, high-energy particles.

Space weather predictions are neither accurate nor timely, and that leaves astronauts—as well as space probe and satellite operators—without enough time to react to dangerous particles flung out by the sun, which can arrive in as little as 30 minutes. Now, NASA is providing $9.7 million to establish a Space Weather Center of Excellence at the University of Michigan, tasked with developing better forecasts.

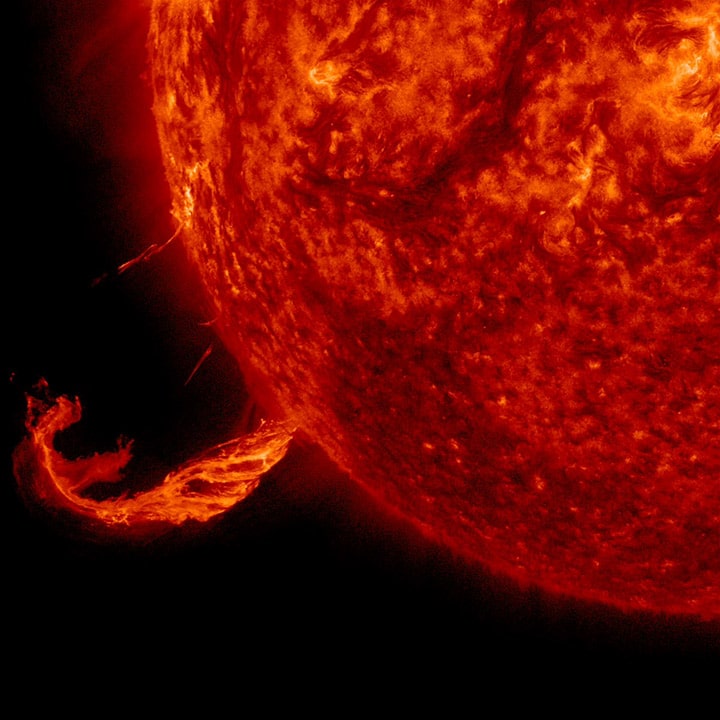

Along with light, the sun is constantly sending a stream of charged particles at the Earth. When the sun has a major eruption, those particles become much more numerous and higher in energy—and more dangerous.

“Very high energy particles would have severe radiation effects on both astronauts and instruments,” said Lulu Zhao, the award recipient and an assistant research scientist in the Department of Climate and Space Sciences and Engineering.

“On Earth, the magnetic field deflects most of those energetic particles, but space instruments and astronauts traveling to the moon and Mars don’t have that protection,” she added.

The most dangerous torrents of particles could kill astronauts exposed during a spacewalk and damage the electronics on space instruments, which are impossible to fix. But, the harm can be prevented if the astronauts stay inside and the instruments are switched off while the particles pass by.

When the stakes are that high, getting advanced notice of dangerous solar activity is mission critical. Now, Zhao will lead an effort to provide that notice through the Center for All-Clear Solar Energetic Particle Forecast (CLEAR Center), with the help of Tamas Gombosi, a professor in the same department who will act as project manager.

The CLEAR Center will build tools that give space instrument operators and astronauts more advanced notice of harmful space weather in any given region of the solar system. While regional space weather forecasts can already be issued for locations on Earth, they have never been extended to the entire solar system before.

The new tool will provide forecasts “similar to the weather app on your phone,” said Zhao. “There, you have a prediction of extreme weather within the next several hours or even days. Our tool will produce a similar product for energetic particles emitted by the sun.”

And like your phone, the tool will issue alerts ahead of dangerous space weather along with 24-hour forecasts so that astronauts and instrument operations can plan their operations around when space weather will be safe. In Zhao’s “best case scenario,” their improved forecasting tool will be ready in time for the Artemis mission’s lunar landing, which is scheduled to begin during a phase of heightened activity in the sun’s regular cycle.

That look into the future will come from a machine-learning algorithm that predicts what the sun’s surface will look like based on real-time images of the sun and how the sun has behaved in the past. That most probable image of the future sun will then be plugged into mathematical and physical models—which would otherwise be limited to current solar data—to calculate the amount of solar particles that any given region of space will experience.

The trick to making these predictions will be acquiring prior observations of solar activity and the corresponding impacts on space weather to train the computer. The current data is scattered among each individual spacecraft that measures solar energetic particles, and focusing on any one particular subset of the data could completely change how the tool forecasts space weather.

“We are all suffering from lacking a comprehensive dataset,” said Zhao.

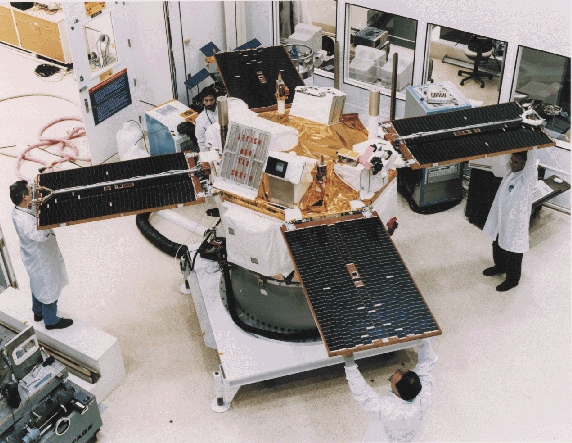

To fill the gap, Zhao and Gombosi plan to compile all of the existing measurements of solar energetic particles and related data from the sun from around 20 different space instruments that have been collecting them since 1973. The team will also continue to collect new data with any operating instruments, such as the Parker Solar Probe and Solar Orbiter. The new dataset will not only train the machine-learning algorithms to predict our solar system’s space weather, but serve as a benchmark dataset for the entire scientific community to develop and validate space weather forecasting tools.

In addition to collecting a more comprehensive dataset, the CLEAR Center will improve space weather forecasts by improving their machine-learning algorithms and refining models of how the sun emits harmful radiation, Zhao said.

The grant is provided by NASA’s Space Weather Centers of Excellence program.