Longer, more intense allergy seasons could result from climate change

Rising temperatures, increased CO2 will drive trees, grasses, weeds to produce more pollen.

Rising temperatures, increased CO2 will drive trees, grasses, weeds to produce more pollen.

Allergy seasons are likely to become longer and grow more intense as a result of increasing temperatures caused by manmade climate change, according to new research from the University of Michigan.

By the end of this century, pollen emissions could begin 40 days earlier in the spring than we saw between 1995 and 2014. Allergy sufferers could see that season last an additional 19 days before high pollen counts may subside.

In addition, thanks to rising temperatures and increasing CO2 levels, the annual amount of pollen emitted each year could increase up to 200%.

“Pollen-induced respiratory allergies are getting worse with climate change,” said Yingxiao Zhang, a U-M graduate student research assistant in climate and space sciences and engineering and first author of the paper in Nature Communications. “Our findings can be a starting point for further investigations into the consequence of climate change on pollen and corresponding health effects.”

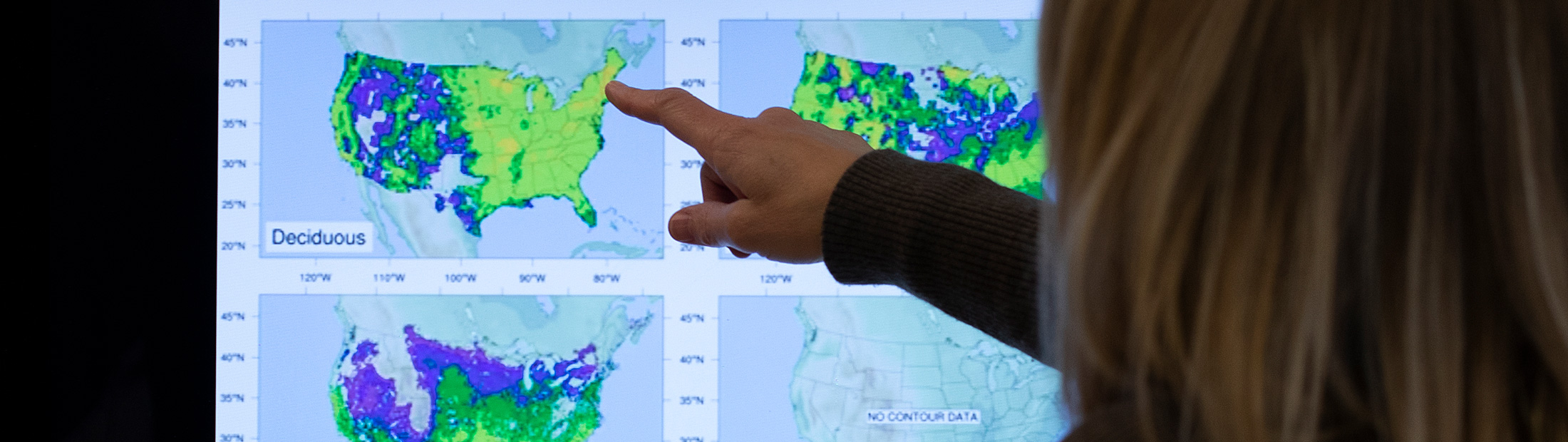

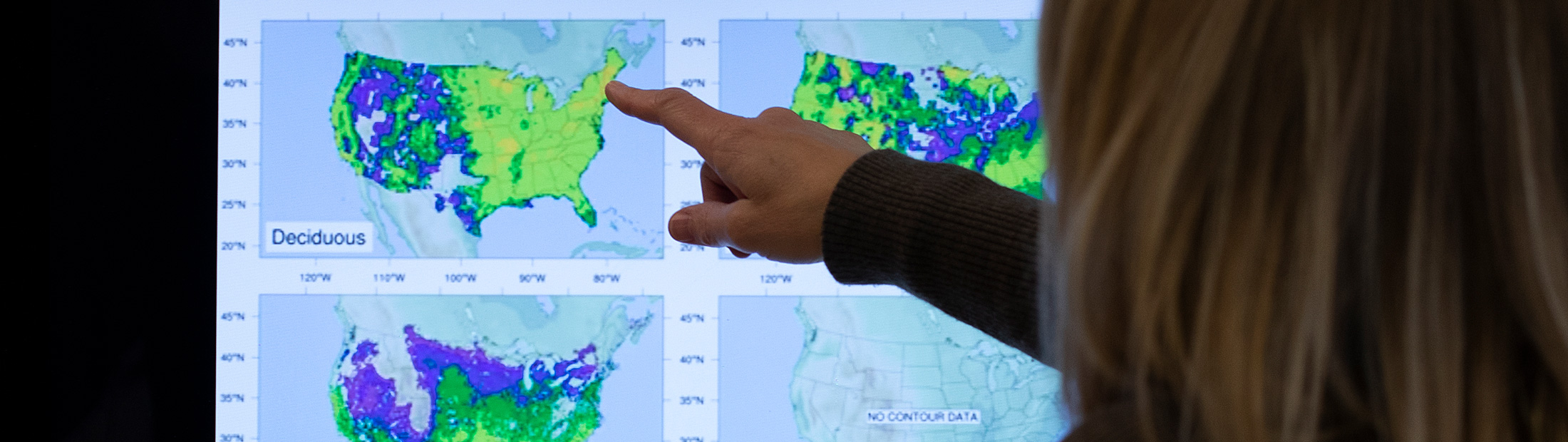

U-M researchers developed a predictive model that examines 15 of the most common pollen types and how their production will be impacted by projected changes in temperatures and precipitation. They combined climate data along with socioeconomic scenarios, correlating their modeling with the data from 1995 through 2014. They then used their model to predict pollen emissions for the last two decades of the 21st century.

Allergies symptoms run the gamut from the mildly irritating, such as watery eyes, sneezing or rashes, to more serious conditions, such as difficulty breathing or anaphylaxis. According to the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America, 30% of adults and 40% of children suffer from allergies in the U.S.

The grasses, weeds and trees that produce pollen are affected by climate change. Increased temperatures cause them to activate earlier than their historical norms. Hotter temperatures can also increase the amount of pollen produced.

Allison Steiner, U-M professor of climate and space sciences and engineering, said the modeling developed by her team could eventually allow for allergy season predictions targeted to different geographical regions.

“We’re hoping to include our pollen emissions model within a national air quality forecasting system to provide improved and climate-sensitive forecasts to the public,” she said.

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation.