What COVID-19 shows about race and health

Highlighting inequities among poverty, infections, and deaths due to COVID-19 in Michigan.

Highlighting inequities among poverty, infections, and deaths due to COVID-19 in Michigan.

Sara Pozzi is the director of diversity, equity and inclusion, Robert Scott is the project manager for special diversity initiatives, and Gabriella Fleming is the NextProf program manager at the College of Engineering.

With African-American communities in Michigan experiencing much higher rates of COVID-19 infections and deaths than their neighbors, Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer has recently issued an executive order to create a Michigan Coronavirus Task Force on Racial Disparities to study, inform the public about, and recommend actions to address health inequities.

As leaders of the College’s Diversity, Equity and Inclusion efforts, we support this initiative, and believe it is important to raise awareness about how hard African-American communities have been hit by COVID-19 and the underlying inequities that feed this tragic situation. Our institution is only as strong as the diversity of the pipeline of talent available; we cannot sit back idly and watch as families and neighborhoods are devastated by the current pandemic.

Many major reports and individual studies detail the ways that racism, social exclusion, and segregation continue to harm the health of African Americans. They account for large differences in health outcomes for African Americans versus their white counterparts in the United States. For example, African-American mothers are more than twice as likely to die during or after childbirth as white mothers.

The current health crisis caused by the novel coronavirus is no exception, with strong correlations between race/ethnicity and disease progression and outcome emerging in U.S. data. Detroit is home to the largest percentage of African Americans of any U.S. city, many still living at or below the poverty line, and many households without access to clean water. These conditions, combined with a prevalence of multi-generational households, single breadwinner families, and lack of access to and trust in healthcare, make these communities especially vulnerable to the spread of COVID-19. As in other areas of the country and the world, the exponential growth of infections in and near Detroit strained the hospital system.

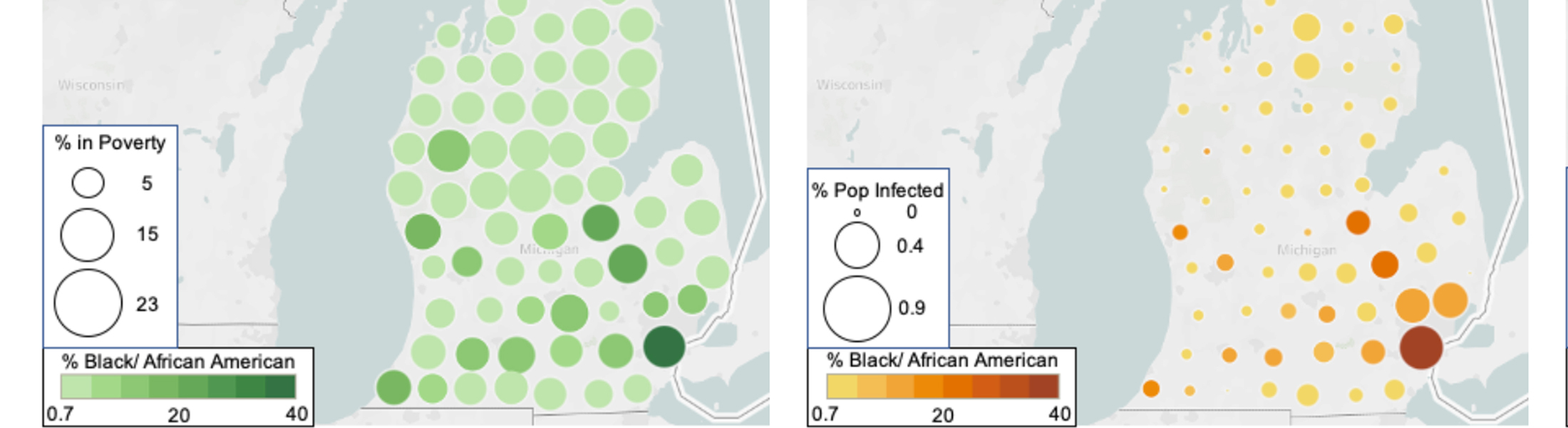

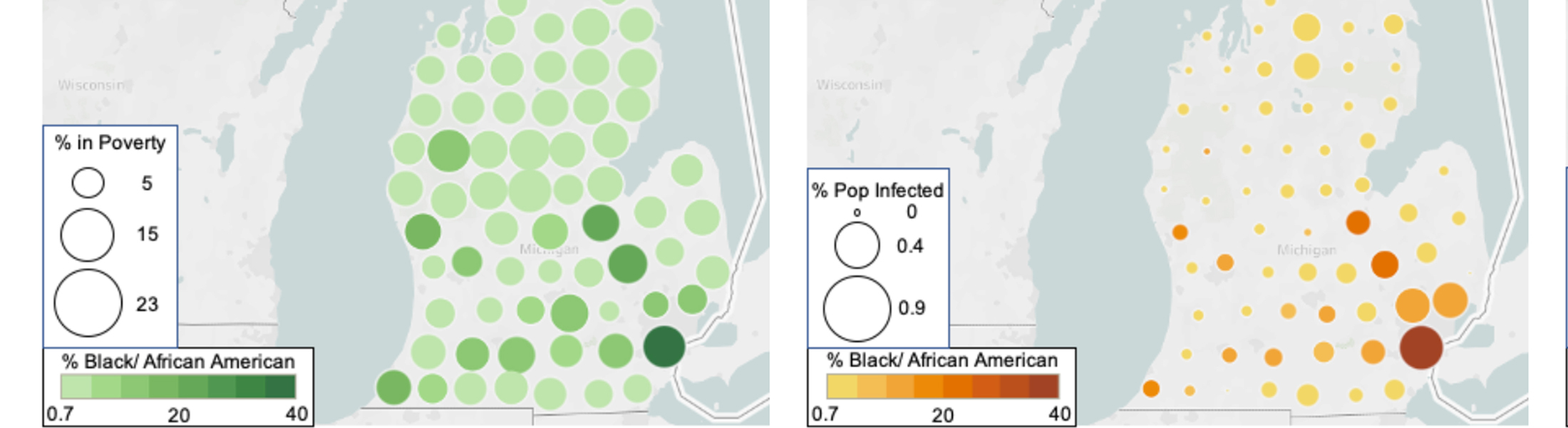

As of Thursday, April 23, a clear correlation and progression can be seen among poverty, infections, and deaths due to COVID-19. The data visualization above shows the geographic distribution by county of the percentage of African Americans in the population and how it correlates with the percentage of the population living in poverty, COVID-19 infections, and COVID-19 deaths.

Of the 10 counties with the highest infection rates, two are on the top 10 list of counties with highest poverty rates and five are on the top 10 list of highest percentages of African-American residents. As of April 23, these five counties—Oakland, Wayne, Genesee, Washtenaw and Saginaw—had 2183 COVID-19 deaths out of 2977 in all of Michigan.

This reflects data recently released by the City of Detroit, that shows COVID-19 cases and deaths are not equally distributed by ZIP code. ZIP codes with lower percentages of African Americans see lower numbers of infections.

A recent article published in The Bridge by our colleagues in the School of Public Health—Melissa S. Creary, an assistant professor of health management and policy, and Paul J. Fleming, an assistant professor in the department of health behavior and health education—clarifies that the disparities stem from racism rather than a biological difference of any significance.

Among the passages that stand out, they wrote, “In this context, when talking about populations and linking their disproportionate infection and death rate to ‘underlying medical conditions,’ what’s really being said is that this population has had poorer access to things like quality housing, clean air, a living wage or preventative health care.”

As a college, our dedication to academic excellence for the public good is inseparable from our commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion. A vibrant, inclusive climate helps us leverage our strengths and make the most of our collective capabilities. Our community includes people from different races and ethnicities, genders and gender identities, sexual orientations, ages and socio-economic backgrounds. Diversity broadens our perspectives and paves the way for innovation. We’re working to ensure that all members of our community have the opportunity to participate fully in all the College has to offer.

With this in mind, one of our aims as a college of engineering is to develop socially conscious minds who can help create collaborative solutions to societal problems. We encourage all members of the Michigan Engineering community to recognize this inequity and others—and play a role in correcting them.