Compostable diapers are the aim of new sustainability startup

Safe and eco-friendly ingredients for personal care have attracted more than $1.5 million in venture capital.

Safe and eco-friendly ingredients for personal care have attracted more than $1.5 million in venture capital.

A new company with an eye to making disposable diapers that aren’t immortalized in landfills has just closed its second round of seed funding—including $500,000 from the University of Michigan’s program to invest in its own startups.

The U-M graduate and faculty startup Ecovia Renewables grows thickeners and superabsorbent biomolecules with teams of microbes, resulting in materials that are safer and more environmentally friendly than conventional synthetic materials. The company has shown that its biodegradable material can compete with conventional disposable diaper absorbency in the lab, and it’s working with manufacturers to put the material into prototype diapers and other hygiene products.

Disposable diapers represent 3.5 million tons of landfill waste in the US alone, or roughly 2.5 percent of the total. Cloth diapers require a great deal of energy, water, detergent and time for parents—and they don’t hold as much liquid, making them harder on the skin of most babies.

“What everybody wants is an environmentally friendly option that still allows the level of convenience that you get with a conventional disposable,” said Jeremy Minty, co-founder and CEO of Ecovia Renewables—and a new dad. Minty earned his undergraduate and doctorate degrees in chemical engineering at U-M in 2007 and 2013 respectively.

Compostable diapers could give us the best of both worlds, but they haven’t been widely adopted in part because the eco-friendly absorbent material isn’t as good as that found in regular disposables. Minty’s company may have an important piece of the solution.

The 4-year-old startup has demonstrated a new bio-based polymer that can absorb as much liquid as the sodium polyacrylate found in conventional disposable diapers. Equally important, it retains the liquid even under pressure, a necessary feature to prevent leaks when the baby’s weight rests on a wet diaper. But unlike sodium polyacrylate, it is biodegradable, eventually breaking down into the carbon dioxide from which it was made.

Disposable diapers cost families hundreds of dollars over the course of a year—around $400 for one child at the lower end to upwards of $800 for eco-friendly diapers. Xiaoxia “Nina” Lin, co-founder, scientific advisor and an associate professor of chemical engineering at U-M, notes research showing that people are willing to pay a premium of up to 30 percent for eco-friendly products. At full commercial production, the Ecovia team expects the cost of the bio-based absorber to be within 25 percent of sodium polyacrylate.

In the meantime, the company is starting off with higher-value applications, such as ingredients for premium cosmetics with eco-credibility. The base polymer, a chain-like molecule that the company is calling AzuraBase, traps water and releases it over time—one of the essential qualities of a moisturizer. As people become more conscious about molecules that could potentially be absorbed into the skin, the bio-based polymer could be especially reassuring.

“It’s edible if someone wanted to actually eat this,” Minty observed with a chuckle. “It is made by microbes that live in soil and that are used in certain fermented foods.”

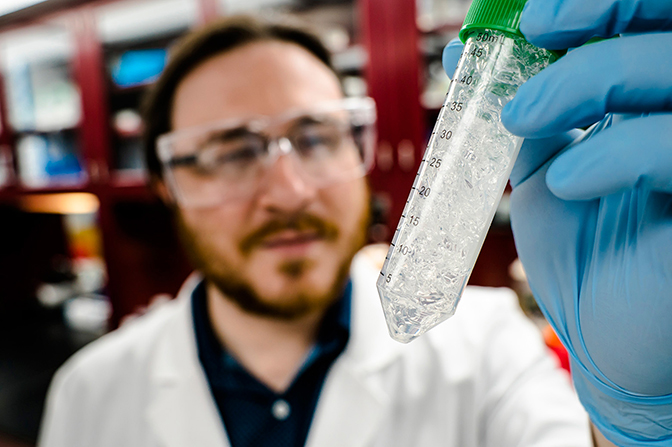

By linking parallel polymer chains together, Ecovia produces a gel known as AzuraGel, the bio-based superabsorbent molecule that could go into diapers. The polymer is already known to break down completely in soil, leaving nothing toxic behind, while the gel will complete compostability testing in the US early next year.

The polymer is produced in fermentation reactors. A team of bacteria and yeast turn a waste product such as glycerol, a byproduct of biodiesel production, into the polymer. Ecovia then purifies the polymer—removing the bacteria and yeast cells, leftover glycerol and any other contaminants.

The concept for the manufacturing process came out of Lin’s lab. While cellular engineering has often focused on designing a single microbe to do a job all on its own, Lin’s team tries to mimic the cooperation found in nature.

“Microbes live in diverse communities, working together to achieve something that any one alone cannot do,” she said. “The idea is to basically recruit specialists like in human society. By having each specialist do really well in their own job but also coordinating together, we can achieve something that is much bigger.”

In addition to providing first-round seed funding, Paris-based Seppic, Inc—which designs ingredients for health and beauty products—has partnered with Ecovia Renewables to develop ingredients for skincare products based on Ecovia’s microbial manufacturing.

For compostable diapers, Ecovia co-founder and chief business officer Drew Hertig says that once they find a business partner in hygiene, he anticipates another two to four years of product and market development. The polymer could also help soil retain moisture, reducing the amount of watering needed to keep crops and gardens healthy.

This round of seed funding brings Ecovia Renewables’ total to $1.6 million.

The Michigan Invests in New Technology Startups (MINTS) program has been part of U-M’s investment strategy since 2012. Faculty startups become eligible to receive funding from U-M’s endowment after partnering with a reputable independent venture capital firm in the first round of seed funding.

Ecovia Renewables also participated in the NSF I-Corps program at Michigan, which is administered by the Center for Entrepreneurship. The company currently holds an option agreement with U-M to commercialize the microbial manufacturing technology.

This article was written by Kate McAlpine and Evan Dougherty.