‘2001: A Space Odyssey:’ From science fiction to science fact

As part of a celebration of the film’s 50th anniversary, leading researchers discussed artificial intelligence and deep space travel.

As part of a celebration of the film’s 50th anniversary, leading researchers discussed artificial intelligence and deep space travel.

Written by Nicole Casal Moore

Does science drive science fiction? Or is it the opposite?

Three leading researchers explored this question in a panel discussion Friday, Sept. 21 – part of Michigan Engineering’s celebration of the 50th anniversary of “2001: A Space Odyssey.” The panel preceded a screening of the film with live orchestral and choral accompaniment. Michigan Engineering and the University Musical Society co-sponsored the screening, which was one of only three such live performances across the country this year.

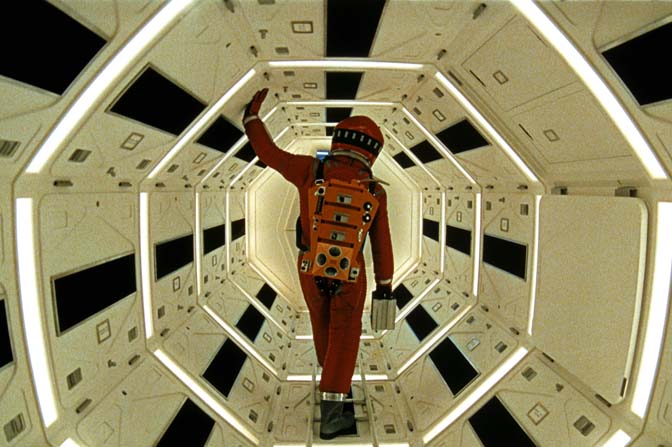

Long recognized as one of the greatest science fiction works of all time, “2001: A Space Odyssey” is celebrated for its technological realism. The themes it raises, in artificial intelligence and deep space exploration, remain relevant today.

“The film predicted with eerie accuracy the future of technology,” said Alec D. Gallimore, the Robert J. Vlasic Dean of Engineering, the Richard F. and Eleanor A. Towner Professor, an Arthur F. Thurnau Professor, and a professor of aerospace engineering.

“It was the first movie I’m aware of that showed iPads, decades before they were invented. It showed space stations and space shuttles as well.”

The film greatly influenced Gallimore, who remembers seeing it in when he was just 4 years old.

“It caused me to become the person I am,” Gallimore said in an interview on Michigan Radio’s Stateside. “I develop plasma propulsion technology that the movie identifies would be needed to propel astronauts to Jupiter.”

He and his colleagues on the panel discussed how far we’ve come from science fiction to science fact in two of the film’s key areas: artificial intelligence and deep space travel.

The HAL 9000 computer that controls the Discovery One spacecraft communicates with the human crew in sophisticated, natural spoken language, said Rada Mihalcea, professor of computer science and engineering and director of the U-M AI lab.

That kind of breezy conversation represents what many consider a pinnacle in artificial intelligence. Mihalcea introduced the audience to the Turing test, developed by Alan Turing in 1950. To pass, a machine must exhibit intelligent behavior that is indistinguishable from a human. And it must demonstrate this through spoken language. HAL may have passed, Mihalcea said. But no machine in real life has.

Still, the field has come a long way. ELIZA the computer therapist was an early natural language processing program developed in the 1960s at MIT. The program used pattern matching to mimic human speech. Mihalcea had a conversation with ELIZA about her talk, to demonstrate its rudimentary capabilities.

The decades since ELIZA have seen exponential advancement, thanks to the explosion of data, the advent of crowd-sourcing and the development of sophisticated algorithms. AI researchers can tap all of these to train intelligent systems.

“Today, we have question answering systems like Siri and Alexa. We have machine translation. We have human-level performance speech processing,” Mihalcea said.

She showed a video of Google’s Duplex AI system booking a hair appointment over the phone.

“There is still a lot to do in terms of developing and building systems that can have natural conversations,” she said. “But progress is accelerating and this promises even more exciting findings.”

Ben Kuipers, professor of computer science and engineering, studied at the MIT AI Lab where ELIZA developed. Kuipers’ advisor had been a consultant on “2001: A Space Odyssey.” Arthur C. Clarke, who wrote the novel the film is based on, even paid a visit to the lab.

In his talk, Kuipers homed in on one of the film’s most startling plot twists.

“HAL ends up being a bad guy,” Kuipers said.

He played a pivotal scene.

Astronaut Dave Bowman commands: “Open the pod bay doors, HAL.”

HAL responds: “I’m afraid I can’t do that, Dave. … This mission is too important for me to allow you to jeopardize it.”

As society moves toward autonomous vehicles, the scene has special resonance.

“If AI systems start doing this, that could be of considerable concern,” Kuipers said. ”I don’t think we’re in immediate danger of this. We have made dramatic progress over the past 50 years. The AIs we’re building now are really more like idiot savants. They are really good at specific things, and really bad at everything else. That approach has a great deal of promise.

“The risks are manageable rather than catastrophic.”

Nonetheless, this progress has encouraged researchers like Kuipers to explore AI ethics – specifically how ethics knowledge is acquired, represented and used, and how robots can utilize those approaches to treat people appropriately.

The film takes place on a spacecraft bound for Jupiter. It was released during the Apollo program, in the year before the first manned moon landing.

While humanity has yet to leave the Earth-moon system, we may in the decades to come. Technologies for a trip to Mars are advancing, including in Gallimore’s lab. He is developing a “Mars engine” that last year broke records for operating current, power and thrust for a device of its kind, known as a Hall thruster.

An engine like this could cut the travel time to Mars by at least one-third, and possibly twice that.

Speed in space travel is important for many reasons, not the least of which is the vastness of the universe.

“If Earth and the moon were about the distance between two of your fingers, Mars would be 8 feet away,” Gallimore said. “Jupiter, 65 feet. Saturn, 110 feet. Neptune longer than a football field away. And the nearest star, Alpha Centauri, would be 600 miles away.

“The galaxy we live in is 100,000 light years wide. The universe is 13 billion light years wide. It’s mind-boggling in size.