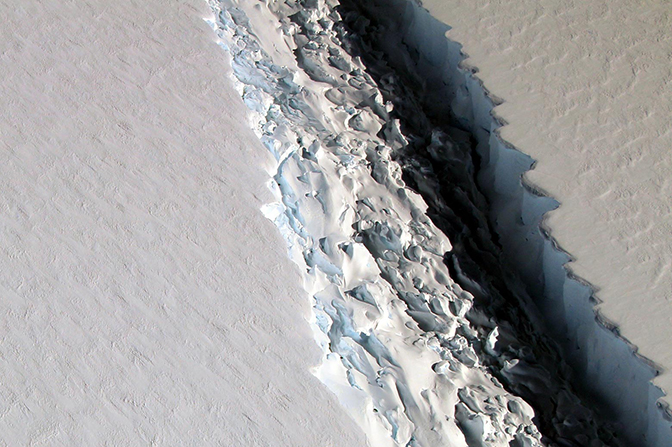

Antarctic iceberg: Researchers explain what might happen next

An iceberg the size of Delaware detached from an ice shelf in the Southern Ocean.

An iceberg the size of Delaware detached from an ice shelf in the Southern Ocean.

An iceberg with a volume twice that of Lake Erie has broken away from the Larsen C ice shelf in Antarctica. Michigan Engineering ice researchers say it will have minimal effect on sea levels, and they outline possible scenarios of what might happen next in this region.

“We don’t know if the ice shelf will be semi-stable, slowly disappear over decades or disappear relatively quickly,” said Jeremy Bassis, an associate professor in the Department of Climate and Space Sciences and Engineering who studies iceberg calving. That’s the process by which icebergs break off of larger ice shelves and ice sheets.

Regardless of which scenario unfolds, this particular iceberg won’t raise sea levels because it broke off from an ice shelf, a formation that’s attached to land, but floats where it juts out over water.

“It’s like an ice cube in a glass of water. It’s already displaced the water,” Bassis said. “It would be different if you were to drop a new ice cube in.”

If the entire ice shelf were to disintegrate, however, that could open paths for ice that’s land-bound today to make its way to the ocean. And those deposits would act as new ice cubes, raising sea levels.

As scientists work to understand what the future will bring to the area, it will be important to study both the ice shelf that remains and the berg that broke off. Mac Cathles, a research fellow in the Department of Climate and Space Sciences and Engineering, is developing tools to remotely measure the mass loss that occurs when icebergs break away from ice sheets. He studies the processes acting at the boundaries of ice sheets, ice shelves and glaciers.

“It is unclear if this latest calving event is ‘business as usual’ or will destabilize the remaining Larsen C ice shelf,” Cathles said. “But I think there is a lot we will be able to learn from studying how this iceberg detached from Larsen C, and by watching how the remaining ice shelf responds after this calving event.”

Bassis has studied similar ice rifts in the Amery Ice Shelf in east Antarctica, exploring why some cracks grow and lead to icebergs and others do not. He is involved in efforts with the British Antarctic Survey to conduct on-the-ground seismology studies of smaller cracks in Larsen C.

He delved into three possibilities for what might happen next.

“One is that ice shelves like Larsen C, continuously every few decades, break off big icebergs and nothing about this is unusual. It could be part of the advance-and-retreat life cycle of the ice shelf. The second possibility is that it may have retreated to a position that’s further back than it’s been before and this may be part of a trend in which the shelf slowly disintegrates as more bergs detach. The third possibility is that it becomes like the Larsen B shelf, in that what looks like business as usual might precipitate a rapid disintegration event: A whole bunch of rifts could become more active and the entire ice shelf could disintegrate.

“At this point, it’s really important to monitor the rifts that exist on the remaining ice shelf and see whether they’re becoming more active.”

This story was co-authored by Jim Erickson.