The Experts’ Experts

Meet the team of trainers, technologists and mentors who make the Leaders and Best a little bit better.

A quiet energy pulses beneath the surface of Michigan Engineering; the rhythm of ideas turning into action. You see it in equations scrawled on whiteboards, experiments being conducted in hushed labs and prototypes taking shape on workbenches across North Campus.

But it doesn’t happen on its own. Every day, behind every professor, lecturer and student is a team of experts who have come here from around the world to apply their skills at the intersection of knowing and doing.

They are the technicians who build and maintain the labs where discoveries take shape. The mentors who help students master machinery and tools. The builders and designers who parse data, sustain experiments and make the Leaders and Best a little bit better.

Here we examine how that network of support and resources shapes a typical day on North Campus. While we can only highlight a small fraction, every research breakthrough and academic success reflects their work and commitment.

8:10 a.m.

Guillermo Rugamas, Groundskeeper

On a chilly November morning, Guillermo Rugamas works methodically, following the dance routine he knows so well. He takes three steps forward, blows the unruly leaves ahead, steps right and repeats. With each pass, the pile next to the Class of ’47E Reflecting Pool on North Campus grows larger.

Born in California, Guillermo grew up in Central America and witnessed first-hand the hardships of life in the tropics. At 18, he moved to Michigan to join his uncle. He enjoys the outdoors, the changing seasons and the opportunities at the University of Michigan. His work keeps him busy year-round—raking leaves in fall, snow removal in winter, mulching and planting in the spring and weeding throughout. “The weeding never ends,” he says. “But it’s kind of meditative. You can think of whatever you want.”

8:30 a.m.

Shawn Wright, Lead Engineer in Research

It’s cleaning day at the Lurie Nanofabrication Facility and the transition—or maybe the transformation—has begun. A group of staff members walks through the secure door to the lab’s changing area. They step onto a tacky mat, then one-by-one don face masks, hair caps, hoods, jumpsuits and booties, which they pull on over regular shoes at the edge of the sterile floor. The final step: disposable gloves.

Among the figures in bunny suits is Shawn Wright, who started in the lab as a student a decade ago. Now he maintains, characterizes and develops processes for lithography and plasma etch equipment. Thanks to staff like Wright, the 13,500 sq. ft. Lurie Nanofabrication Facility supports cutting-edge research and manufacturing on minuscule materials driving global technological advancement.

9:40 a.m.

Alyssa Emigh, Robotics Makerspace Supervisor

“Can you help? I was just looking for you!” explains Andrea Sipos, a freshly minted PhD in Robotics, as she flags down Alyssa Emigh, Robotics Makerspace supervisor. Emigh spends the next 30 minutes adjusting the lab’s air lines so Sipos can demo lens-making technology at a workshop later that day.

Part of the 134,000 square-foot Ford Motor Company Robotics Building, the Robotics Makerspace offers robot design, fabrication, assembly and testing resources and is open to any U-M student. Emigh heads the staff that provides students with training, assures safety and conducts educational programming.

Before joining Michigan Engineering, Emigh crisscrossed the United States building puppets, costumes and animatronics at theme parks. When COVID crippled the entertainment industry, she applied for the robotics makerspace supervisor role. “It was a Hail Mary. I never thought I’d get it,” she said. “But then they called back. I guess I was the right kind of weird.”

10:30 a.m.

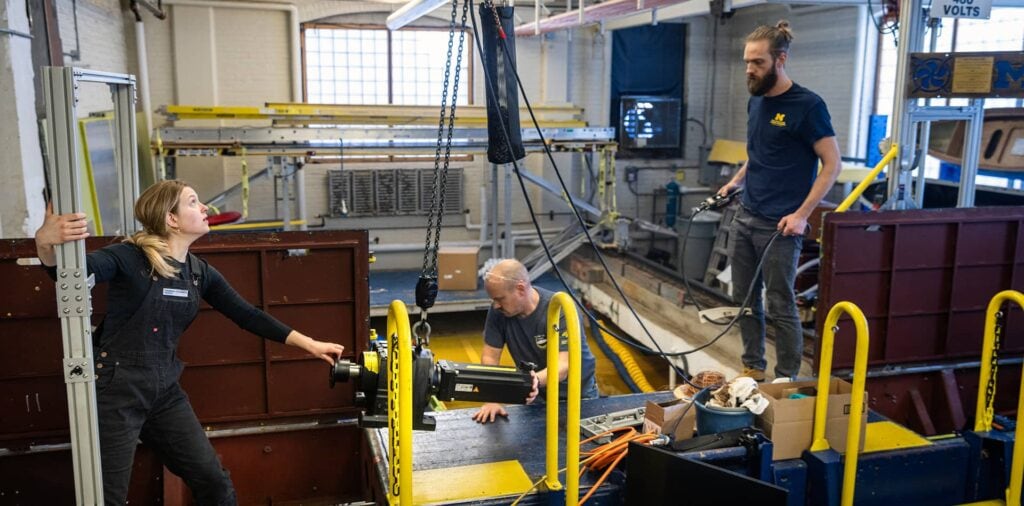

Jim Smith, Research Project Engineer

Jim Smith, research project engineer at the Aaron Friedman Marine Hydrodynamics Laboratory, works with assistant director Anika Szuszman to carefully lower a new motor into the carriage of the lab’s tow tank.

Built in 1904, the tow tank was the first university-affiliated facility of its kind in the United States and is still the largest. Over its 120-year history, the lab has launched some of the most significant innovations in naval architecture, including the fuel saving “bulbous bow” technology that’s used on nearly all of the large cargo ships that transport 90 percent of the world’s goods.

Smith splits his time between maintaining the tank, setting up tests and providing machining, CNC and fabrication training to students. Before joining Michigan Engineering, he spent five years in the U.S. Army’s 82nd Airborne, then worked at the University of Washington developing autonomous underwater vehicles for the U.S. Navy.

“Everything I’ve done—art, hands-on work, time in the Army—helps me in this job,” he says. “It’s taught me how things come together, how to plan experiments and how to humbly share knowledge with students and faculty.”

11:50 a.m.

Sahar Farjami, Laboratory/Classroom Services Supervisor

Dressed in full protective gear, Sahar Farjami turns the handle that controls the crucible furnace, which is brimming with molten bronze. The red-hot lava pours into a ladle, held steady by a student and the class instructor. They are surrounded by a group of wide-eyed first-year engineering students from the ENGIN 100 class. A layer of sand beneath their feet shields the lab floor from the liquid metal.

Farjami manages the Van Vlack Undergraduate Laboratory, which has introduced thousands of undergraduate materials science and engineering students to the characterization and processing equipment used in the field. She maintains equipment, conducts training and leads outreach events. She also co-teaches MSE 577, Principles of Failure Analysis.

Farjami grew up in Tehran, Iran, where she earned her undergraduate degree. She then moved to Japan, completing a master’s and PhD in engineering. After graduation, she became a faculty member at Kyushu University, where she researched electron microscopy and material characterization as the only female, non-Japanese professor in her department. She lived in Japan for 13 years before she and her husband moved to the United States.

“I love this lab. I take care of it,” she said. “I enjoy teaching, but I also love working with instruments and training students on all the equipment we have here.”

1:15 p.m.

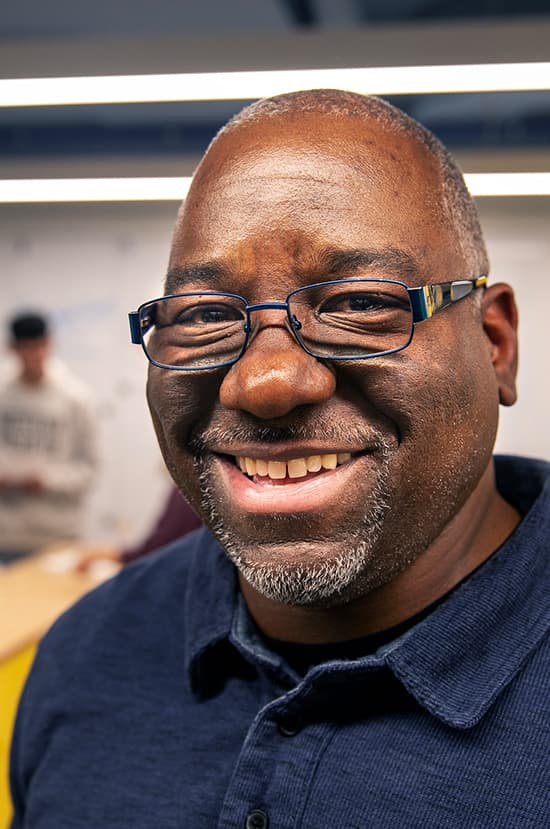

DeAndre Jamison, Laboratory/Classroom Services Manager

DeAndre Jamison feels at home. After years of exploring—nearly becoming a major-league baseball player, working as a corporate engineer, earning a master’s degree in education from U-M, teaching middle schoolers and working on medical equipment at hospitals across four states—he finally found his place at Michigan Engineering.

“This is what I’ve been looking for my entire career,” Jamison said. “This role lets me use my full skillset and have an impact on what the students do.”

Jamison manages the Biomedical Engineering Prototyping Hub, which provides students with prototyping, fabrication and testing spaces, as well as a place to collaborate on new ideas. He also trains students, from undergraduates to PhD candidates, on tools like 3D printers, industrial sewing machines, laser cutters and waterjet cutters.

Beyond teaching manufacturing and project management, Jamison shares life lessons he learned from his baseball days. “Baseball is a game of failure. Even the best hitters fail seven out of ten times. You learn how to deal with adversity and the slump. I try to instill that in the students.”

4:00 p.m.

Sallee Klein, Senior Engineer in Research

“If you picture a fly and all its parts—wings, antennas, eyes, body—that’s the scale of the laser targets I make,” Sallee Klein says with a smile. She builds targets for high-power laser research experiments with Michigan Engineering’s Center for High-Density Laboratory Astrophysics Research. She designs each target based on researchers’ specifications, then sources the parts and builds them under a microscope.

Today, she’s packing a recent batch into transport cases, each cushioned with layers of foam and placed into a kind of soft-sided lunch box. The boxes are then placed into a specially adapted car seat for extra protection during the drive to the airport. Tomorrow, Klein will head to the Laboratory for Laser Energetics in Rochester, New York, to support an experiment.

“Sallee is crucial to my research,” says Carolyn Kuranz, an associate professor of nuclear engineering. “She supports target fabrication for experimental teams across the U.S. and abroad. Few labs in the world do this kind of work for high-energy-density science.”

4:15 p.m.

Meghan Dailey, Machine Learning Specialist

“You’re basically trying to teach a computer how to think like a human does.” That’s Meghan Dailey’s shortest explanation of machine learning. She’s a machine learning specialist at U-M’s Advanced Research Computing. And every week, she makes herself available to anyone at U-M who wants to use machine learning or AI to design, conduct or analyze their research results.

“Obviously there’s a lot of code, a lot of different solutions out there for that type of problem,” Dailey said. “But that’s where we start with explaining to people what you can do with machine learning.”

In 2015, Dailey earned a master’s degree in robotics, becoming one of the first graduates of the then-new program. In 2022, after Robotics had become a full-fledged department, she became its first Alumni Merit Award recipient. Before joining Michigan Engineering, Dailey worked in the private sector, serving as technical lead on defense contracts with the U.S. Navy and the Air Force.

She sees the future of AI in the collaboration between humans and robots rather than in AI taking over the world.

“AI is extremely powerful and there are a lot of different models and capabilities coming out really every week,” Dailey said.

6:00 p.m.

Blake DesRosiers, Lab Technician

In a small room behind a heavy black and white curtain, Blake DesRosiers explains the difference between a root pass and hot pass to a student eager to learn welding. The root pass fills the gap between two metal sections; the hot pass joins the root weld to the groove faces.

DesRosiers trains students at the Wilson Student Team Project Center, a 25,000-square-foot makerspace stocked with lathes, mills, 3D printers, computer-aided design equipment and much more. It’s open to any U-M student, and DeRosiers provides training on how to weld, laser-cut and operate CNC machines.

“This is my first adult job,” says DesRosiers, fresh from Ferris State University’s welding engineering undergraduate program. “I wanted to be in a teaching role where I could help students learn.” Today, he manages the student staff at the Wilson Center, trains team members and runs the machine shop. “I make sure everyone is safe and successful,” he said.