Ice Aces

By learning from Arctic frogs, fish and beetles, a DARPA-funded project aims to reimagine life in the cold.

PHOTOS BY: Marcin Szczepanski

Contents:

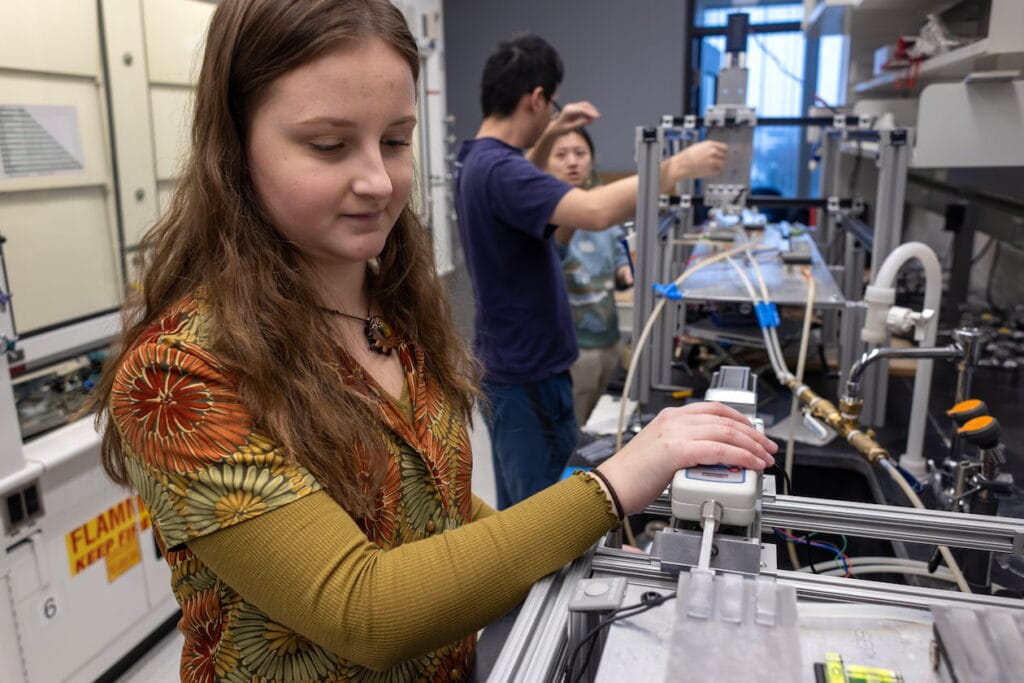

Down a narrow glass hallway in Building 28 of U-M’s two-million-square-foot North Campus Research Complex, inside a cooling chamber, a tiny digital camera is silently watching 400 water droplets. The automated optical system notes when the first microscopic flecks of ice form in each droplet—a process called nucleation. It can also detect propagation, the stage when ice crystals bloom into long chains and cloud the droplet’s interior. The system can test 1,000 samples a day, each spiked with a different set of molecules designed to inhibit the liquid from freezing.

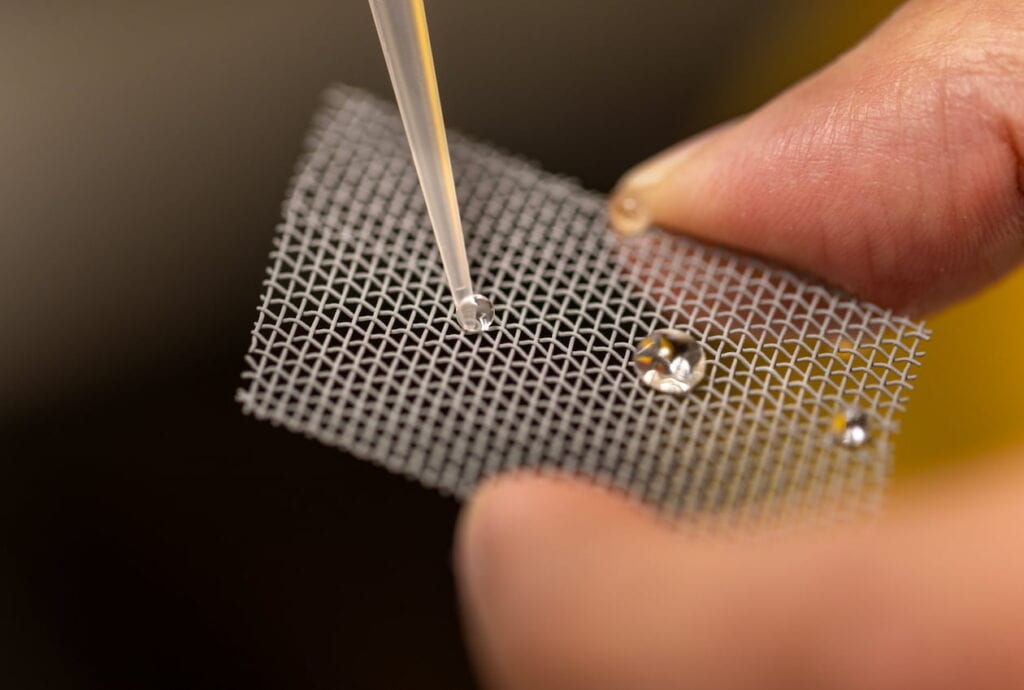

On a nearby workbench, a series of digital cameras is mounted on tripods, their lenses ringed with LEDs. They peer into a row of aquarium-sized plexiglass freezers, watching for frost to form on metal plates the size of postage stamps. The plates are coated with a molecule called a zwitterionic polymer, developed to repel frost and ice from the solid surface.

The lab is the headquarters of the IceCycle project, a 30-month, up to $11.4-million effort funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to reshape how humans interact with ice and cold. It arrives at a time when climate change and geopolitical instability are drawing increased attention to the Arctic—home to 4 million people from eight countries and a vast number of indigenous communities. In this frigid northern region, the United States military has identified challenges—and IceCycle researchers are looking for solutions.

THE ARCTIC HEATS UP

For years, the U.S. military has faced growing unease about its capabilities in the Arctic. Its vulnerabilities were highlighted in 2018 with Operation Trident Juncture, a NATO-led military exercise that involved 50,000 troops, 10,000 vehicles, 250 aircraft and 65 marine vessels from 31 countries. Held in the Norwegian Sea, it was the largest exercise of its kind in more than three decades.

The exercise wrapped up with mixed results. U.S. field medics had to rely on their own body heat to keep IV fluids and blood for transfusions from freezing. Frost jammed weapons and equipment. Frostbite was a constant danger. Melting permafrost created mud that hobbled vehicles.

“The exercise achieved its objectives but did not go as smoothly as would be needed to respond successfully to a capable and modern belligerent [force]…,” the U.S. Naval Institute concluded. “The challenge now is to learn from these lessons and advocate for the revival and evolution of our operational and strategic approach to the high north.”

Funded by DARPA’s Ice Control for cold Environments (ICE) program, IceCycle aims to equip U.S. soldiers with new tools for the Arctic. But it’s also designed to spur technologies that go far beyond the military, making life in the cold safer and more sustainable for the rest of us. Its innovations could help prevent ice from sapping the efficiency of built infrastructure like military and cargo ships, wind turbines and refrigeration equipment. It could also seed new technologies to prevent frostbite, preserve human tissue and—maybe—ensure that you never have to scrape your car’s windshield again.

“IceCycle opens up completely new research directions for us,” said Anish Tuteja, a U-M professor of materials science and engineering and the project’s principal investigator. “What’s also exciting is that it’s structured to encourage the pursuit of applications outside the Department of Defense. I think broadly, there’s going to be a lot of commercial impact from this work.”

For decades, Tuteja has dedicated much of his research to developing coatings that can help free the built world from unwanted ice and snow. IceCycle is enabling his team to pursue that research on an unprecedented scale, doubling the size of his lab space and bringing in partners from across U-M, other universities and the private sector. The team includes researchers from the University of Minnesota and North Dakota State University, as well as RTX BBN Technologies, the tech and defense conglomerate behind companies like Raytheon and Pratt & Whitney. Tuteja is also a professor of macromolecular science and engineering and a professor of chemical engineering.

As they look for solutions, the team is involving Native communities that have called the Arctic home for millennia. They’re also gleaning know-how from other cohorts that have already mastered living in the region: Frogs. And fish. And insects. Even bacteria. Arctic organisms are masters at the three key abilities the IceCycle team is studying: preventing ice from forming, controlling how ice sticks to other surfaces, and perhaps most audaciously, promoting ice formation.

“IceCycle opens up completely new research directions for us. I think broadly, there’s going to be a lot of commercial impact from this work.”

Over the years, Arctic wildlife’s incredible ability to manipulate the freezing process has come to scientists’ attention and found its way into the academic literature. That literature forms the starting point of much of IceCycle’s work, and the project aims to use it in a way that gives credit to the Native lands and people where the knowledge originated. Jodyn Platt, U-M associate professor of learning health sciences, is working to make that happen in her role as the project’s ethical, legal and social advisor. She notes that the project is not physically taking Arctic organisms or their molecules to be used in research. The work is done with molecules that are either purchased commercially or synthesized in IceCycle’s labs.

Still, the organisms where the molecules were discovered have cultural significance to people who live in their native habitats. And their use raises difficult social questions in cultures where people have traditionally adapted to nature rather than trying to control it.

Platt is already reaching out to Arctic communities and other key stakeholders, both to learn from their deep understanding of ecosystems and life in the cold and to ensure that IceCycle benefits the communities that fuel its discoveries. Their input will help the team produce solutions that are safe and relevant in real-world situations.

“A major focus of my work,” Platt said, “is to ensure that we learn from people who are impacted by the things that we do, as opposed to guessing about what people want and think and feel. We hope that the lessons learned can be translated and adopted into the research process and real-world implementation.”

TRADING HUBRIS FOR WONDER

In some ways, the launch of IceCycle echoes the Space Race, when Sputnik sparked both military solutions and a new era of technological innovation. But IceCycle’s 21st-century science holds a key difference, says Abdon Pena-Francesch, a U-M assistant professor of materials science and engineering. He sees the project’s work as shifting the perspective of science toward watching, learning and adapting—in a sense, a pivot from hubris to wonder.

“As engineers, we’re…I won’t say biased, but we tend to design things we understand,” he said. “But in biology, there are so many things that we don’t understand. And there’s a clear path from understanding what happens in nature to putting it out there in the world to help with very real problems.”

The basic principles behind the natural phenomena are well documented—how, for example, a salamander shifts the chemical composition of its blood to withstand the cold, how a centipede encourages freezing in some parts of its body to protect others, or how a bacterium accesses a plant’s nutrients by causing it to freeze and burst its cell walls. But in practice, these creatures rely on an intricate web of systems that evolved over eons—and were too complex to study with the tools of the 20th century.

“We hope that the lessons learned can be translated and adopted into the research process and real-world implementation.”

Recent leaps in computing technology and digital imaging have changed that, opening up the new avenues of study upon which IceCycle is embarking. In its first year, researchers will crunch data from the thousands of test molecules in Building 28, using a combination of human analysis and machine learning techniques developed at North Dakota State University.

The team then plans to narrow the field of potential molecules to around 75. These next-stage candidates will be subjected to a battery of additional tests, using more advanced (and more time-consuming) tools like Raman spectroscopy and differential scanning calorimetry to gather extremely precise information about exactly how each molecule influences the formation and adhesion of snow, ice and frost.

If DARPA deems IceCycle’s innovations worthy, the team could receive a fresh round of funding to scale up production facilities and develop formulations for specific applications. Promising new molecules could begin to find their way into bandages, airplane wings, deicing fluids, topical creams and dozens of other applications, some of which would require FDA certification.

It’s a big ask. But for Pena-Francesch, it’s also an irresistible proposition.

“These animals have had millions of years to develop crazy solutions to adapt to pretty hostile environments,” he said.

“If we can understand them, the applications are endless.”

COLD-WEATHER COHORT

IceCycle aims to find new ways to control the freezing process by learning from Arctic organisms like fish, amphibians, plants and bacteria. They employ natural chemical compounds to manipulate the properties of water and survive freezing temperatures. Here are a few examples.

Siberian Salamander

Native to an area that spans from Russia to northern Japan, the Siberian salamander can survive temperatures of -67 degrees Fahrenheit, freezing solid only to thaw out and walk away when the weather warms. It accumulates the NADES compound glycerol, a sugar alcohol, in its organs. The heavy glycerol molecules don’t freeze and can limit the damage that freezing causes in body tissue and fluids.

Winter Barley

Barley, a grain that’s commonly cultivated in cold-weather climates, accumulates betaine in freezing weather.

The natural zwitterionic compound discourages freezing by making water molecules less mobile, slowing their movement into the alignment required for freezing. Betaine also helps the plants weather drought and high salinity.

Garden Centipede

Found mainly in North America and Europe, the garden centipede produces ice-forming proteins to enhance its resistance to cold.

The proteins encourage freezing in the fluid between cells. This frozen fluid then acts as a barrier to freezing within cells, which is more damaging.

THE POPSICLE EFFECT

The process of ice formation that’s playing out in Building 28 has played a pivotal role in the career of Allison Hubel, a mechanical engineering professor at the University of Minnesota. She has spent years working to understand the natural systems that plants and animals employ to survive freezing weather.

“Water does things that no other substance on Earth does. Its freezing and melting points can be manipulated,” she said. “Nature knows that, and it produces proteins and other molecules to take advantage.”

Hubel has characterized thousands of these natural systems over the years. Through IceCycle, she’s looking forward to a collaboration that takes a page from the millennia of human experience that relied on careful observation and adaptation rather than hazardous chemicals and brute force.

“We haven’t been looking at what’s right in front of our faces,” she said. “DARPA is changing that, and I’m really excited about being able to get independent verification of our research, about having access to big data analysis that could uncover hidden patterns. And the infrastructure that they’ve put in place in terms of commercialization is just amazing. Amazing.”

Hubel specializes in naturally occurring deep eutectic systems, or NADES. NADES are combinations of sugars, sugar alcohols and amino acids that enable certain species of Arctic lizards and frogs to survive cold weather.

Anyone who has ever eaten a Popsicle has experienced the basic principles behind NADES, Hubel says. Those principles underpin the pop’s propensity for separating its sugary flavoring from its icy core, leaving generations of eaters with brightly colored tongues and flavorless lumps of ice.

“These animals have had millions of years to develop crazy solutions to adapt to pretty hostile environments. If we can understand them, the applications are endless.”

The Popsicle phenomenon happens because water separates from sugar and other molecules during the freezing process, leaving the non-water molecules unfrozen. Lizards and other Arctic life take this idea a step further, combining sugars, sugar alcohols and amino acids into even heavier molecules that bind to water inside and between cells, limiting ice formation. This reduces the damage caused by freezing, enabling a seemingly-frozen lizard to thaw out and walk away.

Because NADES are non-toxic, naturally occurring compounds, they hold potential for applications that need to be compatible with living tissues. The team hopes they could eventually be used to protect IV fluids, vaccines and blood from freezing. They could also lead to better cryopreservation of human tissues, making fertility treatments and tissue and organ transplants more widely available and effective.

“Sugar, sugar alcohol and amino acids are natural things that people eat every day, so in a sense they’ve already been tested across lots of different conditions,” Hubel said.

NADES also have potential for nontoxic and environmentally-friendly deicing solutions for aircraft and roads.

A WINDSHIELD THAT SCRAPES ITSELF?

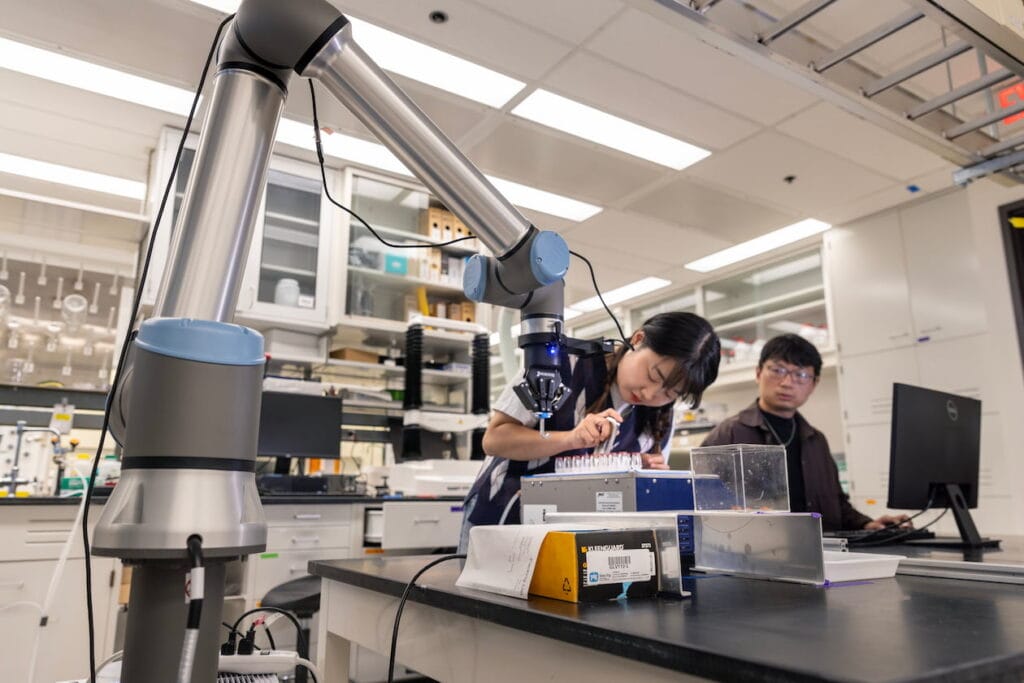

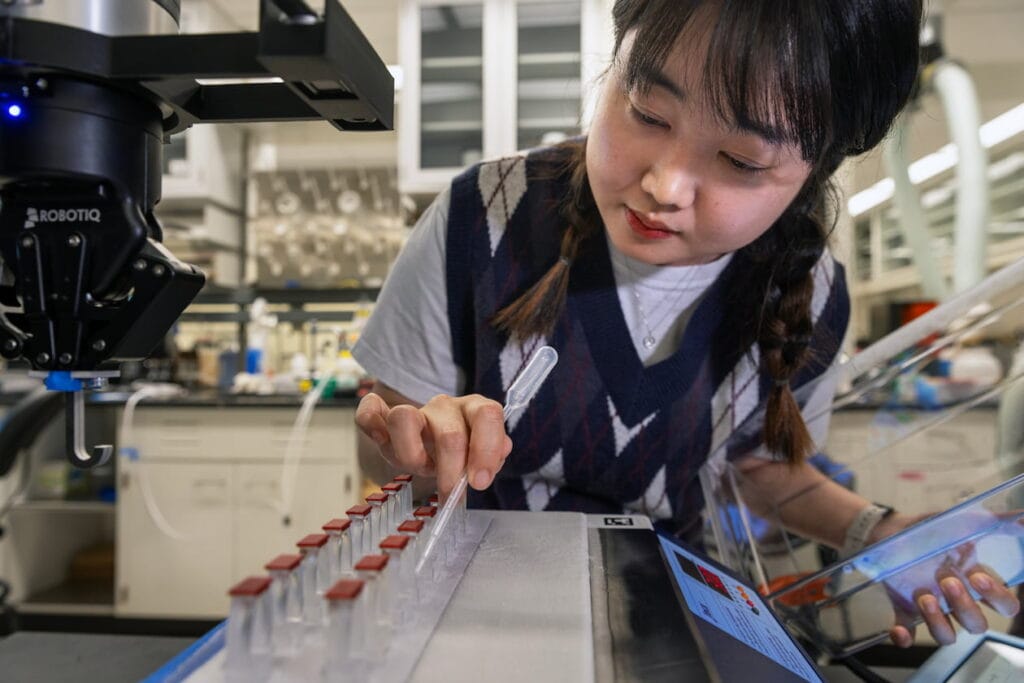

An elevator ride up from the droplet testing lab is Pena-Francesch’s Bioinspired Materials Laboratory, where IceCycle researchers are working with a family of robotic arms. Some are simple pushers mounted on workbenches, held in place by Erector Set-like arrangements of aluminum beams. The most elaborate arm looks more human—satin silver with a graphite-colored shoulder, arm and wrist, cabled to a laptop that feeds it data.

The arms have one job: to dislodge centimeter-square chunks of ice, called cubits, from the temperature-controlled metal plates to which they are frozen. The exact method with which the cubits are detached varies—some are pushed, some pulled, some twisted. The robots measure the force required to remove each cubit in Newton-meters. The action happens over and over again as graduate students and postdocs ready the next round of cubits, pipetting squirts of water into clear plastic cubes to freeze.

The team is gathering data that will inform their efforts to control ice adhesion. For the military, a coating that keeps surfaces ice-free could help ships navigate Arctic areas more safely and prevent frost from damaging equipment. Beyond the military, reducing the burden of ice accumulation could make life in the cold easier and safer, and make many of the machines that power modern life more sustainable.

A major impact could come from more efficient refrigerators and air conditioners, which today consume some 20% of the world’s electricity, according to a 2019 report from the International Institute of Refrigeration. Tuteja explains that the evaporator coils in today’s cooling equipment are prone to freezing up, sapping their efficiency. A coating that could prevent freezing could make future devices up to 30% more efficient. It could also improve the heat pumps that are increasingly replacing fossil fuel-burning furnaces in homes and businesses.

In addition, ice-free cargo ships would use less fuel. Solar panels and wind turbines could produce more power. Power lines could be more reliable and less costly to maintain. And, yes, ice could one day slide off your car windshield under its own weight as you pour your morning coffee.

The technology that could make it happen is based on what are called “zwitterionic molecules.” They’re found in Arctic salmon, as well as other fish and shellfish like lobster, squid and crab. The molecules protect underwater life from the ocean’s crushing water pressure, and in cold waters, they also slow down the freezing process.

“We haven’t been looking at what’s right in front of our faces. DARPA is changing that.”

The key to the non-toxic molecules’ unique properties is their weak electrical charges, which interact with the molecules in water. Water molecules need to move into a specific orientation in order to freeze; they drift into this formation as the temperature drops. But the gentle tug of the zwitterionic molecules’ charges makes water molecules less mobile, lowering their freezing point.

“A large surface coated with zwitterionic molecules can create a thin layer of unfreezable water that prevents ice from sticking directly to the surface,” Pena-Francesch said. “That water also acts as a lubricant that causes any ice that does form to slide off.”

Zwitterionic coatings can also discourage frost on cold surfaces by forcing tiny droplets of condensed water to remain in liquid form, causing them to evaporate rather than freeze and stick.

While NADES’ superpower is their biocompatibility, the zwitterionic molecules developed at U-M shine in their durability. The IceCycle team is working to design a library of zwitterionic molecules and combine them with polymers to make a thin, durable, clear and non-toxic coating.

Ice adhesion is familiar territory for Tuteja. He has dedicated years of research to developing coatings that prevent things from sticking to other things, and perhaps no other substance has been as enticing or as vexing as ice.

Dislodging ice presents a maddening array of variables, he explains, and substrate and ambient temperature are just the beginning. Causing ice to slide off requires a completely different amount of force than popping it off, for example. Large areas require a different strategy than small areas. And snow? Don’t even get him started.

This is why IceCycle’s ice-adhesion work, as well as the rest of the project’s research, is after not one-off molecules, but rather a “library of properties”—a set of variables that quantifies specific properties of ice behavior, along with an arsenal of ways to control it.

It’s an approach that requires an entirely new scientific vocabulary. Tuteja explains, for example, that no standardized system exists to measure how ice sticks to a surface. But the data the robot arms gather as they pop off cubits could inform the foundation of such a system. Their data could be parsed into technical requirements for a given application, and those requirements could, in turn, be matched up with the ice-influencing characteristics of a given molecular cocktail.

“There needs to be an understanding of the physics behind the problem, the mechanics of what is happening. Why is the material showing the property that it’s showing?” Tuteja said. “If we can understand that, we can work to improve the properties we want, or we can find other materials that are likely to produce similar results.”

SPRAY-ON ROADS, CAVES OF ICE

At a third IceCycle lab, an electric hum emanates from a silver walk-in freezer. Inside, visible through a small window, is a sprinkler that sprays water onto a series of beams and curtains. Days of frozen spray have manifested a phone-booth-sized landscape of ice and snow.

Here they’re testing proteins that encourage freezing, perhaps the most daunting variable IceCycle is studying. By inducing water to freeze at higher temperatures, the project aims to enable humans to use ice as a building material. Researchers envision powders that a soldier or a hiker could use to turn packed snow into an ice cave, and sprays that could convert mud into an ice road capable of supporting heavy vehicles.

Such products could also buy time for cold-weather communities to adapt to climate change by firming up the frozen lakes and ice roads that form integral parts of transportation networks.

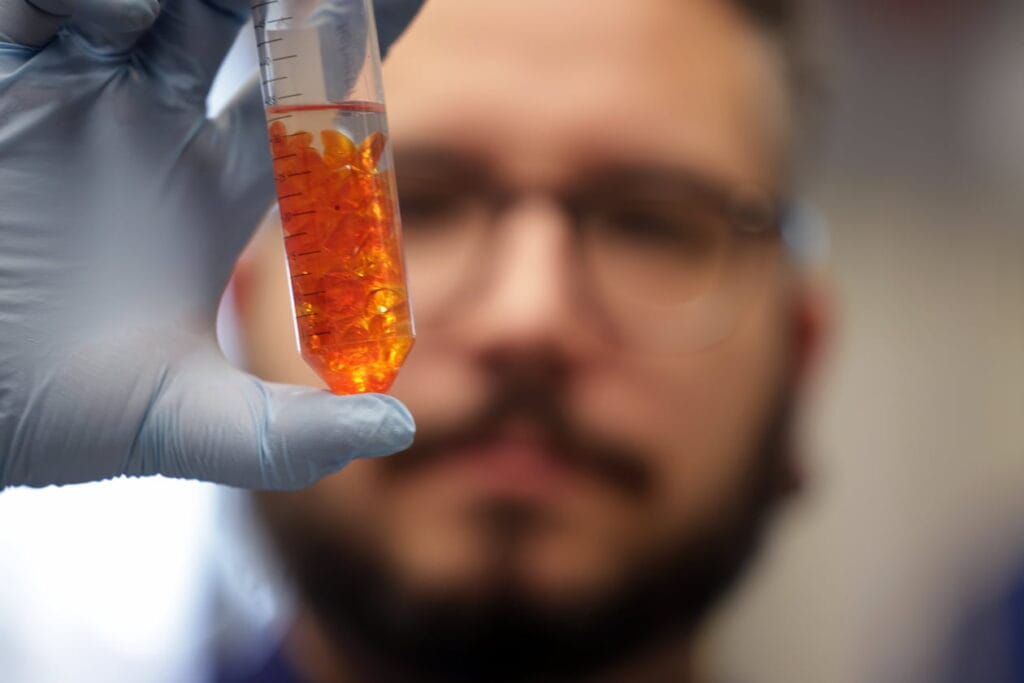

The proteins that could make it possible have been observed in a variety of Arctic bacteria and animals including the garden centipede, found mostly in North America and Europe. Bryan Bartley, a scientist at RTX BBN Technologies, explains that the insects use ice-nucleating proteins to cause freezing in parts of their bodies where it will do little harm. This controlled freezing creates barriers that protect more vulnerable areas while they wait for warmer weather, or until they can generate anti-freeze agents like NADES.

The proteins take advantage of the same intricacy in the freezing process as zwitterionic polymers—the need for water molecules to orient themselves in a particular way to solidify. But instead of slowing down this process, ice-nucleating proteins accelerate it. Their orderly lattice structures (called motifs) mimic the arrangement of frozen water molecules. This helps nudge liquid molecules into freezing position, raising the temperature at which they’ll turn to ice.

Ski resorts already use ice-nucleating proteins to boost the volume and longevity of the snow that billows from their artificial snowmaking equipment. But IceCycle aims to make products that are many times more potent by identifying new strains of ice-nucleating bacteria and testing them in thousands of different combinations.

The synthetic biology lab at RTX BBN is developing a database of proteins that are likely to cause ice nucleation. Some are already known, while others have only been theorized based on observations in bacteria.

“It’s very exciting science, and we’ve never had this level of resources to be able to explore it. There will be a lot of new learning.”

Bartley’s team plans to produce thousands of the proteins at RTX BBN’s Seattle lab and ship them to North Campus for testing. There, Tuteja’s team will use the droplet chamber in Building 28 to identify the most promising candidates, then do more exhaustive testing on the finalists in the freeze chamber.

“You can imagine that if you have two proteins from two evolutionarily distant species, their structural motifs are going to be very different—they’re achieving ice nucleation in very different ways,” Bartley said. “But if we put them together, they could have a synergistic effect, nucleating ice in multiple directions at once. It’s not rocket science, it’s just that nobody has done it before.”

Like Bartley, Tuteja draws inspiration from the molecular jiu jitsu that enables Arctic organisms to turn freezing from a danger into a tool—to thrive in their surroundings while also being in harmony with them.

IceCycle aims to take a page from that playbook, enabling humans to both adapt to cold places and to reduce their impact on those places. The work begins with noticing what has been in front of us all along.

“There’s so much that we have learned from nature,” Tuteja said.

“It’s very exciting science, and we’ve never had this level of resources to be able to explore it. There will be a lot of new learning.”