Car country plugs in

The Midwest holds the greatest automotive workforce the world has ever known. With help from U-M’s new EV Center, it’s gearing up to power an electric future.

A 1965 Mustang convertible, “poppy red” with a white top, sits in the front bay at Illi’s Auto Service, two blocks west of downtown Ann Arbor. Owner Larry Young’s website highlights “classic car service” as just one of more than 20 auto repair jobs offered here. Nearby, a mechanic dives into the troubles of a late model Volvo, while a Saturn convertible quietly waits its turn in the corner.

Contents:

This place has been fixing cars of one sort or another since 1946, and clues to that long life are all around—the ornate brickwork atop the building, the 1980s-era Ford tow truck parked outside, the awnings out front, the old newspaper clippings tacked to the wall.

Illi’s is a survivor. It endured the widespread arrival of automatic transmissions in the late 1950s. It adapted to new emissions technologies in the 1970s. And it rolled with the introduction of onboard computers in the 1980s. As for what’s coming next … Illi’s may not survive that in its current form.

Electric vehicles (EVs) represent the largest auto industry shakeup since, perhaps, the introduction of the assembly line more than a century ago. Moving consumers from the internal combustion engines (ICE) that have powered their transportation since birth to something fundamentally different means major changes at all levels of the business.

Each new law designed to speed that transition, and each new pledge from automakers about how quickly they’ll reach EV-only status, ratchets up the pressure on the industry. And nowhere is that pressure felt more than in Michigan and the surrounding region.

For so long, this has been the center of the U.S. automotive industry. Detroit’s “Motor City’’ moniker is well-earned, and even as major U.S. auto manufacturers have diversified and spread their operational footprint around the globe, this part of the Midwest has remained the focal point.

But that dominance, along with the jobs and investment it brings to the region, has been increasingly under threat for more than a decade now. Tesla’s arrival as the earliest standard-bearer for EVs shifted much of the industry’s focus to Silicon Valley and Texas.

To shore up the Midwest’s standing and harness its expertise and infrastructure, a different workforce will be needed. New technologies and new training will be required to ensure that the region—with Michigan at its epicenter—can pivot its formidable automotive infrastructure to an EV-driven future.

“We need to secure the Michigan workforce not only for its own sake, but because it will cascade and accelerate the growth of the EV industry overall,” said Anna Stefanopoulou, the William Clay Ford Professor of Technology and a professor of mechanical engineering at U-M. “We have tremendous engineering and product development expertise in the auto sector here in Michigan. We need these powerful hands, minds, hearts and networks to boost the EV transition.”

An EV Center at U-M

In 2022, state lawmakers underscored that urgency by earmarking $130 million for the creation of the University of Michigan Electric Vehicle Center. It serves as the hub of the university’s workforce effort, and will be a home to its cutting-edge research into the vehicle technologies crucial to widespread EV adoption.

Alan Taub, a longtime auto industry executive and now the Robert H. Lurie Professor of Engineering and a professor of materials science and engineering at U-M, is the center’s director. The University, he said, offers expertise that goes beyond the three current drivers of mobility: connected vehicles, autonomous vehicles and electrification.

“We’re somewhat unique in that we have user centers where universities and industries come together to advance their technology and educate their workforce,” said Taub. “With the state’s $130 million grant, we’re bringing everything we have to offer on electrification. It’s not starting from scratch, it’s more pulling these things together and putting them on steroids.”

The EV Center’s mission features three tracks: technological innovation, workforce development and education, and new facilities to centralize and enhance U-M’s research and teaching.

Industry officials are helping to set priorities for the EV Center from the outset, Taub said, noting there are still questions surrounding what is most needed. How do we tap the expertise and infrastructure already available in Michigan, and where do we need to expand our capabilities to accelerate the transition for all?

For places like Illi’s and owners like Young, all this means hard choices are coming. In his early 60s, Young is still working to determine how much he’s willing to invest in an electric future.

“If we were to go forward, our plan would be to move more toward steering and suspension work,” Young said. “We’d probably leave alone the electronics that would require much more investment in training and tools. But we think we can find growth by offering electrification of classic cars.”

Jobs in ice-related auto parts manufacturing and repair

in the continental united states

Source: Anna Stefanopoulou

Planned Battery Plant Capacity in Gigawatt-Hours (GWh)

in the Continental U.S. by

136-98 GWh/Year

Georgia – Kentucky – Michigan

97-47 GWh/Year

California – Kansas – North Carolina – Ohio – Tennessee

46-31 GWh/Year

Nevada

30-4 GWh/Year

Alabama – Arizona – Colorado – Indiana – South Carolina – Texas

Under 4 GWh/Year

Florida – New York

Source: Argonne National Laboratory

View data visualization description

Overview

The data visualization is an outline of a map of the continental United States containing two different data sets and legends to highlight both the number of jobs in ICE-related auto parts manufacturing and repair per state and the planned battery plant capacity measured in gigawatt-hours per year, per state.

Values

View the full data set for jobs in ICE-related auto parts manufacturing and repair in the continental U.S and the data for planned battery plant capacity in the continental U.S. by state.

Presentation

The first data set is displayed by color coding states using a blue monochromatic scale of five numerical ranges to represent the number of jobs in ICE-related auto parts manufacturing and repair per state.

The highest number of jobs occurs in Michigan, Indiana, and Ohio, with anywhere from 20,001 to 40,000 workers. The second highest amount of jobs occur in California, North Carolina, and Texas, with 10,001 to 20,000 workers. The third highest amount of jobs occur in, with 10,001 to 20,000 workers. The least amount of workers (0 to 1,000 workers) is seen in the northwest and prairie regions of the United States.

The second data set is displayed on the map using varying battery charge levels to indicate one of five numerical ranges denoting the planned battery plant capacity in the continental U.S.measured in gigawatt-hours per year, per state. Data for seventeen of the forty-eight continental states is provided.

The highest amount of planned battery plant capacity is seen in Georgia, Kentucky, and Michigan, with 136 to 98 gigawatt-hours per year. The lowest amount of planned battery plant capacity is seen in Florida and New York with less than 4 gigawatt-hours per year.

[End of long description.]

A changing job market

To get a sense of the auto industry’s future landscape, it helps to crunch some numbers. Thankfully, Stefanopoulou has done just that. Early in 2022, she analyzed which areas of the industry are likely to be most impacted by the move to EVs, and where they’re located.

The assembly, automotive parts manufacturing and maintenance and repair of vehicles in the United States accounts for roughly 1.8 million jobs. Of those, Stefanopoulou determined, over 300,000 are tied directly to ICE-related parts and vehicles.

“We expect there will be a significant shift in the types of jobs and locations of jobs—even growth in parts manufacturing—in the auto industry as a result of the transition to EVs,” Stefanopoulou wrote last year. “Specifically, we expect ICE-related parts jobs to be lost and, in some cases, moved to large EV-parts manufacturing and material processing sites.”

On the assembly side, industry leaders assume EV powertrains, and specifically the battery-electric powertrains that are simpler than their ICE counterparts, could require up to 30% less assembly labor. That would result in 72,000 fewer U.S. assembly jobs.

But of all the auto jobs categories, Stefanopoulou found that ICE parts manufacturing positions are most vulnerable. Up to 146,000 of them are potentially on the chopping block if EV production and sales continue to increase. More than half of those at-risk posts are in Michigan, Ohio and Indiana. Repair jobs, like those at Illi’s, are the second-most vulnerable category nationwide.

Fortunately, Michigan also has expertise in the battery-based propulsion technologies crucial to the EV transition. And the state is expected to see some of the nation’s highest growth in battery manufacturing capabilities by 2030, according to an Argonne National Laboratory report that looked at where automakers and joint ventures are planning new facilities.

The new activity won’t automatically offset ICE-related jobs lost. But with the right training, workers displaced from fossil fuel-dependent industries could be a wellspring for the workforce needed to staff new plants according to a 2023 report by Li-Bridge, a public-private consortium launched by the U.S. Department of Energy. The report adds that reskilling should be prioritized to reduce impacts on communities and people.

The nation needs to dramatically scale up battery manufacturing to meet future vehicle demand. On top of that, advancing battery technology—longer ranges, lower costs and faster recharging—is key to selling the public on EVs.

“Right now, we’re working to understand what the relevant courses are for these needs and how best to organize them around two areas: master’s level course offerings to help address the worker pipeline for new hires and retraining or upskilling for the current workforce,” said Jason Siegel, a U-M associate research scientist and the EV Center’s director of education. Everything is on the table, from curriculum guidance for educators at multiple levels to creating a fast-track master’s engineering program.

For the state and region, there is plenty of knowledge to draw from. As the Michigan Economic Development Corporation stated in 2023, “Michigan is home to the fifth-largest advanced manufacturing workforce in the country, with the highest volume of mechanical and industrial engineers in the U.S. The state’s research and development capacity is second to none. In 2022 alone, Team Michigan attracted more than $14 billion in electric vehicle and battery investment.”

Statistics compiled by the nonprofit Environmental Defense Fund in 2023 showed Michigan ranking first among states for EV investments and third for new EV-related jobs.

At the head of the EV Center’s workforce retraining efforts is Ashlee Breitner, managing director at U-M’s Economic Growth Institute and lecturer for Michigan Engineering’s Center for Entrepreneurship.

“There is so much going on right now across the state regarding workforce development—new program development, collaboration across current offerings,” she said. “We want the EV Center to be the focal point for making sure those efforts truly create an effective talent network. And where there are gaps, we want to ensure we’re helping to fill them to meet employers’ needs.”

Challenges will be different depending on your place in the U.S. automotive ecosystem—whether you’re one of Detroit’s “Big Three” automakers, a major parts supplier or a repair shop owner like Young.

What follows is a look at the EV transition through the eyes of people at different levels of the industry—what they expect for themselves and the industry, as well as what they need from state officials and U-M to prepare for it.

The major automaker

One building—actually, one seven-structure complex—dominates Detroit’s skyline. And for nearly three decades, the Renaissance Center has been a home to General Motors, giving the largest U.S. automaker a top vantage point on the comings and goings of the Motor City.

Fittingly, it’s a broader perspective GM officials are after these days as they look to mold their workforce into one that can handle the demands of electrification. Workers with specialized expertise remain valuable, but those who understand the wider EV picture and how their work fits into it are prized.

“We have people that had focused on the thermal modeling of combustion,” said Paul Krajewski (BSE MSE ’89, MSE ’91, PhD ’94), director of the Vehicle Systems Research Lab at GM’s Global Research and Development Center in Warren, Michigan. “These skills can apply to thermal management in electronic systems or battery systems in vehicles. So it can be about using your fundamental skills in a different way.

“But I think overall training for the EV future needs to be focused on a systems level. While it may be great to have very specific domain knowledge, say in battery chemistry or electrodes, it’s all controlled by electronics and software and, in some cases, leverages machine learning.”

Michigan Engineering has offered its ME 565 course—Battery Systems and Control—since 2011. More than 50 engineers from GM have taken the course since then, along with another 500 Michigan Engineers.

“The ability to integrate and apply those to new problems and think about things more holistically is a skill that I think is really important to develop,” Krajewski said.

We need [Michigan’s] powerful hands, minds, hearts and networks to boost the EV transition.”

If only those kinds of workers were more plentiful. With the push toward electrification and autonomous driving, the industry has been battling over engineering talent for 15 years. Relative newcomers, like Tesla, and Waymo in Silicon Valley, have also siphoned off capable workers from Michigan and the Midwest.

Sanjeev Naik (MSE EE ’88), director of GM’s Propulsion Systems Research Lab, said the company utilizes a two-tiered approach to developing its EV workforce.

“We want to bring along the workers that we already have and retrain them,” he said. “There are lots of fungible skills across the organization, lots of strengths which can translate and grow and retrain into the EV space. Secondly, we look at hiring in new people with specific skill sets which we need to complement our retraining of the existing workforce.”

U-M and GM have a long history of collaborating on workforce training. In 2005, for example, they launched the Global Automotive and Manufacturing Engineering master’s degree—a multidisciplinary online program customized for the company, but open to others. To date, hundreds of GM engineers around the world have been through it.

It’s one of the ways Michigan Engineering partners with companies on continuing education and professional development. The College has delivered 85 custom courses, including many based on its three-day short course on vehicle electrification and four-day workshop on battery manufacturing.

Earn your graduate degree at Michigan Engineering

Michigan Engineering is home to top-ranked graduate programs—on campus and online. We’re building off the University of Michigan’s greatest strengths to reimagine what engineering can be, close societal gaps and serve all people.

The education and support goes both ways. Industry leaders sponsor many of Michigan Engineering’s EV-related student teams. GM is a platinum sponsor of the MRacing formula SAE team, which pivoted from ICE to electric in 2022, and a silver sponsor of the Solar Car Team. Ford is a top sponsor of those teams, as well as the SPARK electric motorcycle team.

Leo Lavigne, former SPARK president who graduated with a mechanical engineering degree this spring, landed a position in the Ford College Graduate Program. He’s cycling through the company and the country in different roles. Lavigne knew his work on SPARK would prepare him for the future.

“All the jobs that these students apply to, they have the opportunity to show their work and show that they’ve worked on vehicles at a very high caliber,” he said last spring at his final SPARK competition. “We’re doing things that very very few schools are doing and people just really like to see that.”

Video transcript

[On screen text]

A University of Michigan student team built an electric motorcycle and hired a professional rider. Now they race against professional motorcycles.

Peter Jaskoski

It’s not for the faint of heart, but it’s for people who like a challenge.

[On screen text]

The students traveled with their bike to South Carolina.

Leo Lavigne

So today we unpacked our trailer, got the bike ready to go. We’re just excited to be out here and racing and hopefully get a win today.

…

Atlas is a 120 volt, 800 amp motorcycle. It boasts top speeds of 150 miles an hour. It’s got about 110 horsepower. We work with software, electrical mechanical, and we’ve got a business team as well. We’re one of the few teams at the University that actually competes against manufacturers. So there are no colleges here today and what we do is we race against Honda, Kawasaki, Ducati, and what it may be and we just are really pushed and driven to compete at a high level with those companies that have millions and millions of dollars to spend on it.

Peter Jaskoski

Being on a team like this, it’s incredibly invaluable. I’d say if you are an engineering student or any student at the University of Michigan for that matter, there’s nothing more immersive than being on a team like this.

Asha Rajagopal

Electric vehicles are like one of the fastest growing fields for software and then having the ability to say that I like yeah no I was the one writing all this code I was the one doing all this work will make a huge difference. Being on this team has given me such a valuable part of what you need in order to get a job and excel in a computer science field.

Peter Jaskoski

Just from my experience I’ve gotten exposed to technologies and research and parts and supply chains and like the whole world of developing a product from design to actually getting it built in real life. Something that’s also incredible is working with sponsors you know having meetings with CEOs and VPs of companies, you know pleading your case for a sponsorship, working with really cutting-edge companies on developing stuff — it’s incredible. It’s personally how I got a job in my interview and I feel like it’s how many others have and will.

…

Well we just got back from the first Spark race ever where we finished completely without any glitches. We turned in some serious lap times and we’re all ecstatic.

Asha Rajagopal

It went really well. I mean yeah man we got personal records on like almost every lap and there was no glitches with any of the software and like everyone’s just really happy.

[On screen text]

The team will attempt to push the bike even further.

Leo Lavigne

Yeah so this morning we came here after winning last night and uh everything was in accordance to plan. The bike functioned really well yesterday, we sorted all of the issues out. Went out for the race. Was looking really good. He was getting some of his fastest lap times of the weekend.

Peter Jaskoski

We slide off the track. It honestly it doesn’t look too bad. We’re happy he’s okay, first thing. He’s walking around. I can tell he’s probably just more mad that he crashed it and he probably feels really bad for us. Honestly, we don’t want him to feel bad. We’re happy he’s okay. The bike is, looks… I mean it’s not on fire so for an electric bike like that’s okay. Spirits are high here he did turn to the fastest lap we’ve had all weekend today.

Leo Lavigne

On the last turn, on lap three or four, the rear set, the foot peg dragged and caused the rear tire to give out and the bike slid into the grass. David got up. Everything was good, but you know we’re disappointed to see the crash.

David McPherson

I just pitched it in and the peg hit the ground and when the peg hits the ground it picks the front wheel up off the ground and then you go by. Do I guess we figured out the limitations of the lean angle

and we’ll make some adjustments, you know, move my pegs up and farther and hopefully we won’t have that issue anymore, but I guess you got to go past the limit to find out what the limit is and man I feel bad.

Leo Lavigne

We’ll come out of this with a positive. We got a win yesterday and although we did have a crash, the bike’s good and we’re looking forward to the next one.

Manasvini Nannapuraju

Now it has battle scars but it looks cool, it adds character to the bike.

Leo Lavigne

Right now the ceiling for battery technology and motors is unknown and we think it’s much higher than where we are right now. All the jobs that these students apply to, they have the opportunity to show their work and show that they’ve worked on vehicles at a very high caliber and so we’re doing things that very very few schools are doing and people just really like to see that. The team will be back and we’ll be hungrier than ever.

The line workers

On May 31, 2023, Mike Booth stepped before the camera and delivered some hard truths to his audience—the membership of the United Auto Workers (UAW). As the union’s vice president, he’d been tasked with addressing the industry-wide move toward EVs.

First, he somberly noted the “gut-wrenching plant closures’’ of the last few years and criticized Detroit’s Big Three automakers for shifting jobs overseas despite record profits. It’s messaging that’s not uncommon from the UAW, which counts more than 383,000 active members.

Yet it now has a heightened sense of urgency due to EVs. Not only is there concern about offshoring, but other—largely non-union—states are wooing auto companies as they pivot. And while UAW leadership supports the EV transition that’s already underway, their concerns over ensuring what they consider a “just” transition are palpable.

“These must not only be union jobs, but they must be jobs that maintain the wages, benefits and health and safety standards that generations of UAW members have fought for,” Booth said. “We must also make sure that any of the workers who lose their jobs as a result of the shift to electric vehicles have a place to land. That means a right to the jobs that are being created and a right to the proper training.”

Kevin Gotinksy, the UAW’s director of EV strategy, detailed the training and safety concerns of rank and file workers, using changes in battery manufacturing as an example.

“EV battery work is different from any normal auto industry job—a lot of high skillset jobs, tons of chemicals we don’t normally come across in a regular manufacturing facility, the exposure to the higher voltages that ICE workers would not see. So learning that aspect of it, the risks and dangers and getting the necessary training to work in those areas is key.”

At the same time, the battery industry is in “desperate need” of trained workers, according to a 2021 survey by advanced battery trade association NAATBatt. When it comes to skills on or near the manufacturing floor, the biggest voids identified in the survey align pretty well with Gotinsky’s list—high voltage electrical skills, fire response, battery testing, assembly and recycling. These skills should be taught at trade schools and in-house programs, respondents said.

Stefanopoulou is working with Macomb Community College’s Center for Advanced Automotive Technology to co-develop the curriculum and hands-on lab modules for an associate’s-degree EV technician and fleet operator specialization. More programs like it are on the horizon through the EV Center, working closely with the state of Michigan’s EV Jobs Academy, its Talent Action Network and its Sixty by 30 goal—for 60% of adults to have a postsecondary credential by 2030.

“We have a tremendous opportunity to leverage the access we have at U-M to tech-based educational tools and pair it with investment in the EV Center to create retraining solutions,” Breitner said. “These solutions can be experiential in a way that gives our current workforce the hands-on experiences they need to be resilient in the future of EV manufacturing.”

The parts manufacturer

Things could be worse, a lot worse, for Eric Partington and Lear Corporation right now. Parts suppliers are expected to see the biggest impact from the EV shift, thanks in part to the fact that EVs have fewer moving pieces. And many companies with ICE-specific product lines are having to redefine themselves to stay relevant.

“There’s such massive change going on in the industry, no question,” said Partington (BS ME ’95), Lear’s vice president of e-systems global strategy and product management. “Many of our competitors’ current products are heavily reliant on ICE.”

But Lear, known for its expertise in automotive seating and electrical systems, appears well positioned to move ahead based on what it already has in place.

“Essentially, 100% of our products at Lear are ambivalent to what the vehicle’s drive train is,” said Partington. “We have upsides right now in our ecosystems and electronics businesses, and there are avenues for increasing our products through contributions for the electric powertrain.”

Other parts companies, like Auburn Hills-based BorgWarner, are expanding product lines through acquisitions.

“[BorgWarner] has a long history of producing parts for petrol-powered vehicles,” stated the Financial Times in September 2022. “It generated 19% of its revenue last year from selling turbochargers, which use exhaust from combustion engines to rotate a turbine and boost power.”

To diversify its portfolio, BorgWarner has been purchasing companies with EV-related products and services—a means of expanding its footprint in the game.

“Acquisitions are part of BorgWarner’s plans to refashion itself for the electric era,” the article continued. “… Dealmaking can bring companies new technologies to sell to their current customer base. According to Dealogic, the number of deals in the U.S. auto supply chain as of September 2022 was 72, increasing from 49 for the same period two years ago.”

Lear has made its own acquisitions over several decades in preparation for the future. Most recently, the company finalized acquisition of Germany’s I.G. Bauerhin in early 2023 and, in 2022, it purchased Kongsberg Automotive’s Interior Comfort Systems. Both moves bolstered Lear’s Thermal Comfort Systems division.

The company’s expanded portfolio allows it to combine different areas of its operation—heating efficiency, ventilation and active cooling, and lumbar support and massage—in the design of automotive seating. With it all under one roof, Lear can introduce new technologies while controlling the weight of the seats.

Five years ago, I wasn’t even worried about [EVs]. But if we don’t go that route, we’re going to shrink.”

“Seats are a large component in any vehicle, and our ability to reduce their weight can really impact and help extend the range when it comes to EVs,” Partington said.

So what does a company like Lear need from the workforce at this point? To explain, Partington pointed to a key EV component, the battery’s emergency shut-off system, used to control voltage in case of emergency or accident.

In the ICE age, batteries ranged from 12 volts to 14 volts—all that was necessary to spark the ignition and run your lights, radio and clock. EVs now coming off the line feature batteries that can go up to 800 volts.

“Technical talent across the engineering spectrum is really critical,” he said. “For example, we need mechanical engineers who can work on electrical systems because of the high voltages and the resulting heat transfer. Mechanical engineers in those areas are in short supply and very critical.”

That sort of interdisciplinary breadth is part of the EV Center’s DNA. An example is Mechanical Engineering’s ME 599 “Lithium Battery Ecosystem and Life Management,” being offered for the first time in fall 2023 to engineering students as well as those in U-M’s School for Environment and Sustainability. While many details are yet to be hammered out, additional new courses and degree programs in the works will bring different fields under the same umbrella.

The mom and pop garage

Three miles south of Illi’s, just off Industrial Highway, you’ll find Ron’s Garage—a newer repair shop, if you can call a 40-year-old business new. Amid a bustle of post-lunchtime activity in May 2023, owner Ron Cowen struck a note of certainty about the future of his business in the EV era.

“Five years ago, I wasn’t even worried about [EVs]. But if we don’t go that route, we’re going to shrink,” Cowen said. “It creates a new opportunity for us. People ask me all the time ‘What are you going to do when the cars are electric?’ I say, ‘I’m going to fix electric cars.’ Everything that moves eventually fails. It’s just going to be a different type of repair in my eyes.”

Cowen has seen the demands on his garage change before. Two decades ago, engine repair made up a far larger portion of the work his mechanics did. Now, it’s mostly routine maintenance like oil changes.

Hybrids, with their internal combustion engines paired with electric motors, will continue to need occasional oil changes. EVs will not—automakers tout their lower maintenance requirements as a key selling point. But Cowen sees plenty of future need for work on cooling and electrical systems, suspension and steering. At this point, the issue for Ron’s Garage is the training of its mechanics and technicians.

“We’re not part of the factory, so we don’t get our training from the manufacturers but through factory manuals,” Cowen said. “In Michigan, there’s no EV certification yet.”

The state of Michigan currently offers seven different certifications for different aspects of a vehicle’s operation, plus a master certification for those who complete all of the individual programs.

In the early stages of EV introduction, however, companies like Tesla have often kept information about their vehicles close to the vest. And that can be a problem when working on cars that utilize hundreds of volts. In 2022, The Verge reported that “the vast majority of auto repair professionals do not have the training or equipment to repair EVs.”

“We need for the information to be out there, to make sure we have access to it,” Cowen said.

“If it’s available to the aftermarket, then trainers will eventually get to it and make a curriculum with it.”

Li-Bridge, the DoE-organized group, calls out maintenance and repair as a future workforce gap that’s exacerbated because “the U.S. lacks nationally recognized curricula or accredited training standards and certifications to offer a clear path for these next waves of prospective workers.”

Breitner said collaboration will be essential.

“It is critical that we leverage partnerships to train educational providers—whether they are at a community college or at an employer—to ensure that, as information becomes available, we have an activated network to quickly disseminate that information to the current and future workforce,” she said.

U-M labs keep rolling

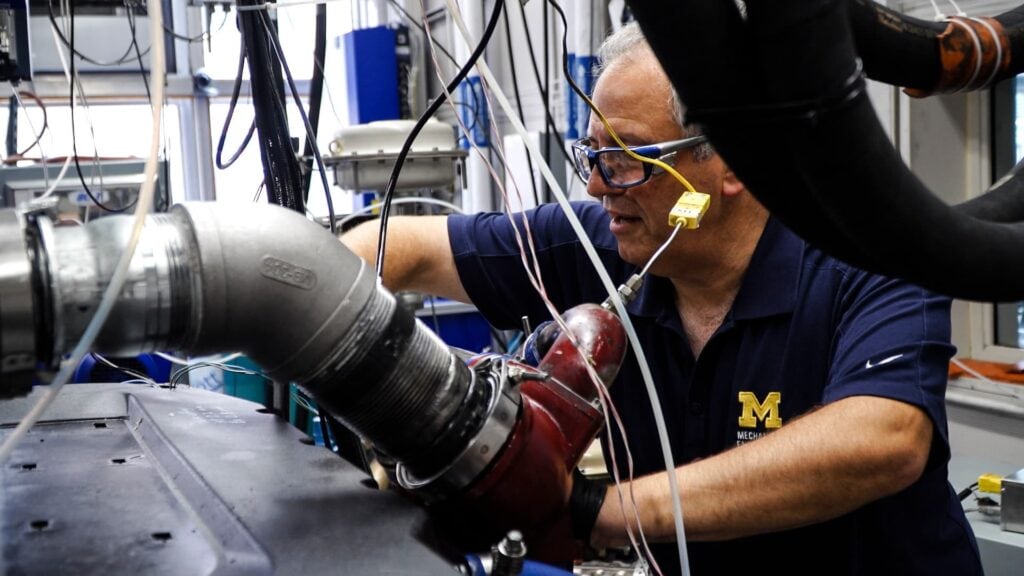

The Walter E. Lay Automotive Engineering Laboratory, also called the Auto Lab, is a microcosm of the shift underway around it. First opened in 1957, it has served as both launching pad and proving ground for ICE-related technologies ranging from controls and combustion to thermodynamics and fuel efficiency. In recent years, it has pivoted to prioritize technologies that will aid in the EV transition.

André Boehman, a U-M professor of mechanical engineering and the lab’s director, has long worked on biofuels. He says the lab’s work on engine efficiency, hybrid powertrains and low-carbon fuels won’t stop. It can’t. They’ll play essential roles in the shift to a more sustainable mobility system.

But the lab is undergoing a major renovation that will make batteries a focal point. Soon, researchers will be able to explore how to boost batteries’ performance and stretch their lives with embedded intelligence that will assess their state of safety for re-use or recycling.

“We want to create, at the module and pack-scale level, a battery safety laboratory where we develop innovative techniques for sensing how they fail and how to manage that risk,” Boehman said.

Education has always been as much a part of the Auto Lab as research. The lab recently collaborated with the EV Center to host a battery boot camp for community college instructors across Michigan—one example of how the facility can support learners in the wider community.

Just across the Lurie Fountain from the Auto Lab, on any given work day, the U-M Battery Lab bustles at maximum capacity. Inside is one of only a few university-based battery pilot lines in the nation, and the only one in the heart of the auto industry. Academic and industry researchers from around the world build and test battery concepts there.

The plan is for the Battery Lab to expand into a new EV Center facility on North Campus, and add a teaching line where students can learn, hands-on, how to make and test batteries with the tools used in industry. But facilities take years to get approved and built, and the College understands there’s a need right now. So the lab has leased an 8,000-square-foot facility off campus as a temporary home for a second pilot line slated to open in early 2024.

One hundred and twenty years ago, when assembly lines first began churning out vehicles, the auto industry showed how Michigan’s ideas, people and materials could literally change the world. And with electrification ramping up, the state and U-M are marshaling the resources to do it again.