Engineering tough

Michigan engineering alum Linda Zhang has the daunting task of bringing America’s bestselling vehicle into the electric age.

Written by:

Photos by Levi Hutmacher and Brenda Ahearn

No pressure here, but imagine for a moment that national and global media were constantly tracking and reporting on your latest work project and describing it in any of the following ways:

“… as important a release as the Model T was back in 1908.”

-Yahoo Finance

“… will strike down social barriers.”

-InsideSources

“… it could accelerate the move toward electric vehicles, which scholars say is critical for the world to avoid the worst effects of climate change.”

-The New York Times

“… the future of mobility will meet America’s favorite ride—a momentous encounter … for all of us, whether we drive, bike or walk.”

–The New Yorker

That’s the special kind of weight on the shoulders of Michigan Engineering alum Linda Zhang. After years in development, the Ford Motor Co. brings its fully electric F-150 Lightning pickup—scion of the bestselling pickup in the United States for more than 40 years—to dealerships this spring.

Expectations are high from a crowd that includes everyone from Ford and pickup fanatics, to climate change activists and the electric vehicle industry. The Lightning is meant to be all manner of things, including Ford’s boldest foray yet into the quickly crowding electric vehicle market as well as one of the most important offerings to get the masses to embrace a technology that could save the planet.

Zhang’s metaphoric shoulders, however, seem built for the challenge. As chief nameplate engineer for the F-150 Lightning, her fingerprints are all over the design, development and delivery of the vehicle, the creation of its new manufacturing plant, and Ford’s marketing campaign. In addition, she’s playing a leading role as the Lightning’s marketing ambassador.

“She’s great to work with. She can obviously be the leader and drive results, but also be a caring mentor to the group. For her and the team to have brought me in and made me feel like a valued voice has really been incredible”

Anthony Magagnoli, Lightning’s off-road experience manager

Her time at the University of Michigan, which began as a 16-year old, first-year student, provided her with two degrees in engineering as well as an MBA. That means Zhang (BSE EE ’96, MSE CE ’98 (Dbn), MBA ’11) has the chops to design your next pickup, help create the plant to build it—and then sell it to you.

Last year Lisa Drake, Ford North America’s chief operating officer, credited Zhang with a “unique combination of engineering and business acumen.” And her team members offer similar praise for her skillset.

“The F-150 Lightning team has been incredible to work on and it really starts from Linda on down,” said Anthony Magagnoli, Lightning’s off-road experience manager. “She’s great to work with. She can obviously be the leader and drive results, but also be a caring mentor to the group. For her and the team to have brought me in and made me feel like a valued voice has really been incredible.”

Zhang’s starring role with the Lightning has made her something of a celebrity in the last two years. She is the project’s outward face—spending an afternoon with President Joe Biden, landing on the cover of Time magazine, appearing in front of cameras and microphones for countless media pieces on the pickup, and as a featured player in Ford’s own promotions.

She is not the only U-M alum contributing to Lightning’s design and rollout. In May 2021, Ford released a series of videos touting different aspects of the pickup featuring key contributors. A half dozen of those appearing on camera had U-M degrees, ranging from mechanical and electrical engineering, to MBAs, to one philosophy degree.

Chris Skaggs (MBA ’00), another Michigan Engineering alum with a key role on the Lightning’s production end, sees exactly what Zhang has taken on. “She’s got a very tough job, to both design the vehicle and launch it,” he said. “I’ve got a tough job to build it, but we work together well. And she’s a great person.”

In person, however, the tackler of tough jobs is without pretense. Zhang is accommodating, puts on zero airs, and is matter-of-fact about who she is and what she has accomplished. If she feels some sense of the moment—of pressure from her central role in all this—she offers no hints. What comes across, time and again, is quiet confidence. Call it an engineer’s belief in the product of her work.

“This truck is a better tool than we’ve ever made,” Zhang said.

Where we are

The move away from internal combustion engines (ICE) toward EVs has accelerated dramatically—driven by concerns over climate change and the role played by traditional auto emissions. It’s a trend approaching its crescendo right now with nearly every major carmaker on the planet having announced plans for hybrid or all-electric offerings. Some even have self-imposed deadlines for producing electric vehicles only.

Consumer interest in sedans has plummeted since the turn of the century. In 2021, Bloomberg delicately stated, “The death of the sedan is the biggest car trend of the decade.” In place of sedans, SUVs, crossovers and pickup trucks have benefitted from shifting driver preferences, with sales rising.

To this point, the bulk of EV offerings have been sedans; think the Toyota Prius, Nissan Leaf and various models of Teslas. But consumers’ growing aversion to sedans means many people have been waiting for a reliable electric pickup to reach the market before abandoning their traditional vehicles.

That’s why industry analysts have eyed an electrified F-Series pickup as a potential game changer. The series has been responsible for the bestselling trucks in the U.S. since the first days of the 1980s, with the F-150 leading the way.

And it’s far from a crowded market right now. At the start of 2022, someone shopping for an all-electric pickup had just two options: the Rivian R1T and GMC’s Hummer EV. In January, Tesla announced its love-it-or-hate-it Cybertruck would not arrive until 2023, while Chevrolet unveiled its Silverado EV, with a similar timeframe for delivery.

All this makes the timing of the Lightning’s arrival seem fortuitous. But make no mistake, the stakes for Ford are high.

The Blue Oval sells roughly 900,000 F-series trucks each year, to the tune of $40 billion. So tinkering with the formula for the U.S.’s favorite vehicle is not to be taken lightly. And introducing a new version while maintaining the connection with traditional ICE pickup owners is a knife-edge for Zhang and Ford officials to walk.

In May, analyst Joseph Spak of RBC Capital Markets wrote, “The F-150 is their Golden Goose. They have to protect that franchise. It’s imperative for Ford to gain that beachhead in electric pickups now to maintain their dominance.”

Linda (张宁宁)

“My dad always said I had just the craziest questions when I was little,” Zhang said in December. “I always wanted to know how things worked— how the clouds formed, why they were the shape they were or, you know, what was going on at the center of the Earth. Just crazy things I would ask in order for me to draw connections.

“My father promoted it, saying, ‘You’re always full of curiosity and you’re always coming up with crazy ideas of how to do things that are maybe different or better.’”

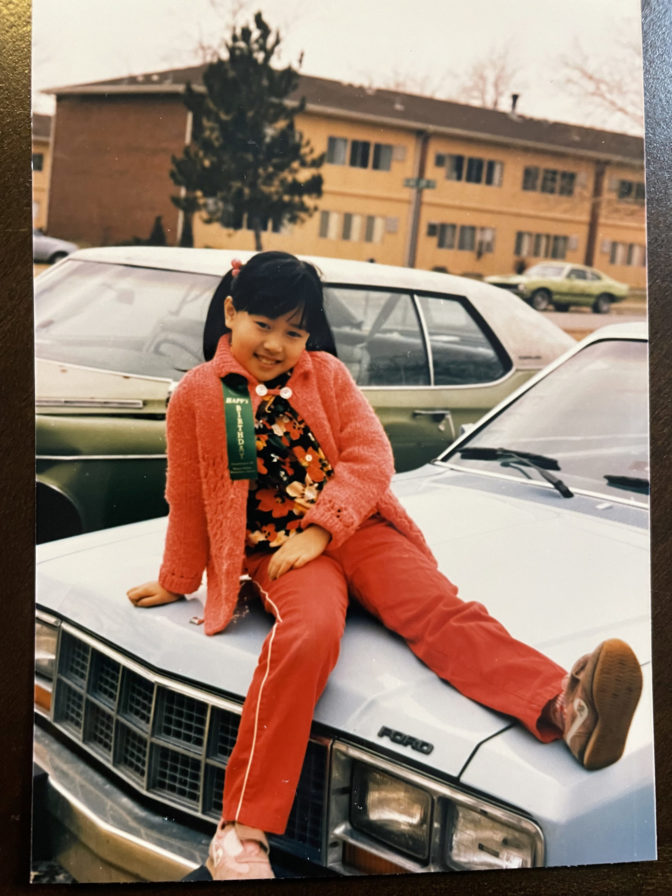

Given where we see her today, it’s an odd footnote that Zhang’s first ride in a car wasn’t until 1985, when she was 8 years old.

“Even on the eastern side of China, in the 1980s, there just weren’t that many cars,” she said.

That same day, she checked off her first airplane flight as well. A year earlier, her father, John Zhang, had entered a doctoral program at Purdue University. The car and plane brought Zhang and her mother, Mei, from their home in China’s port city of Ningbo to the American Midwest to join him.

“We were definitely on our own out here, the three of us,” she said. “Back home, there were always grandmas and grandpas and aunts and uncles. But, you know, we had a pretty nice community here in the U.S. too.”

They’d arrived at the tail end of the school year, giving Zhang just enough time to make a few friends before her first summer break.

“When you’re a kid and you don’t know the language, being with other kids is easy,” Zhang said. “They don’t need much to really hang out, to play or become friends. So the language barrier wasn’t really a big issue.”

The pace of her previous education in China put Zhang ahead of children her own age in the U.S. In third grade she was taking fifth- and sixth-grade math classes. With the encouragement of her parents, both engineers, she continued to move at her own pace, as if that first car ride gave her permission to accelerate.

“In school in China, we had these mandatory afternoon naps,” she said. “I hated that. When we moved to the U.S., no more mandatory naps. And I loved it.”

She arrived on campus in Ann Arbor the same year she became eligible for a driver’s license—a different experience than most, but one that Zhang embraced.

“I got to enjoy a lot of the college experience, but I was 16, so it’s not like you’re going to be able to get a fake ID and head out to the bar,” she said. “So maybe I missed out on some of that.”

Zhang came in with the goal of finishing her undergraduate degree in three years. She committed herself to her studies during the week to allow herself some latitude on the weekends. History shows that her early dedication to work-life balance paid off.

“I went to parties,” she remembered. “I actually met my husband my freshman year at a house party on Division Street. We were friends for a long time before we ever dated. We’ve known each other 29 years and have been married for almost 20.”

Zhang earned her bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering right on schedule. That same year, she started her Ford career at the age of 19. Two years later, she had her master’s degree in computer engineering from U-M Dearborn.

In 2002, she returned to U-M, entering the Stephen M. Ross School of Business for night classes. She would finish several years later with an MBA.

As Zhang’s profile has risen, she has often wound up as the subject of media coverage, with writers discussing her story through various prisms they bring with them.

Some have homed in on her immigrant background. A sub headline from The Drive read: “Zhang came to the U.S. when she was eight years old without knowing any English. Now she’s the brains behind the Ford F-150 Lightning.”

Others have combined her immigrant background with her gender. “Ford’s Chief F-150 Engineer is a Female Chinese Immigrant, and That’s Awesome” read an online headline from motor1.com.

And still other articles note how Zhang might be seen as an “unlikely” or “surprising” choice to lead Ford on this crucial project. That may be because Zhang does not fit the traditional white, male paradigm of an engineer in the auto industry. Women made up only 23.6% of workers in automotive manufacturing as recently as 2019.

For Zhang, if others choose to assign some deeper meaning to her story, so be it. She simply does what her parents encouraged her to do in pursuing knowledge on her own timeline.

Asked how she would encapsulate her own life, she said simply: “Just be who you are. Be yourself.”

Engineering tough

Certain crowds might give you the benefit of the doubt on a new product, but truck owners … not so much. A great deal of what Zhang and her Ford team have done with the Lightning has been centered on developing an electrified pickup that can go toe-to-toe with consumer expectations. In the pickup truck universe, that means a product that is “tough.”

“The electric pickup owner is going to want the same things as a regular truck owner does,” said Michelle Krebs, an executive analyst with Cox Automotive. “They’ll expect it to be able to go anywhere, be tough and durable and carry heavy loads.”

So that’s why, in the summer of 2019, Zhang could be found at a railyard surrounded by pickup trucks and train cars.

In a demonstration put on by Ford, a prototype F-150 Lightning pulled over 1 million pounds of double decker freight train cars for 1,000 feet, to the surprise and delight of a handful of older truck owners. And behind the wheel, Linda Zhang.

“No other truck has ever done this,” she tells the observers in the clip, “but we’re going to do it.”

Once completed, Ford loaded 42 F-150 trucks onto the freight cars and repeated the process with a total towing load of 1.25 million pounds

“When you think of EVs, you don’t typically think of tough, of capable,” Zhang said. “A lot of people immediately think of a vehicle like the early Prius models. To bring people out of that mindset, we really needed to be able to demonstrate that EVs can be tough and that electric power is just as powerful, if not more so, than mechanical power.”

“Tough” can mean all kinds of things. Essentially, today’s electric vehicles are batteries on wheels. To get to a typical range of 200 to 300 miles per charge, the onboard battery, usually lithium-ion, needs to pack in as many cells and modules as possible.

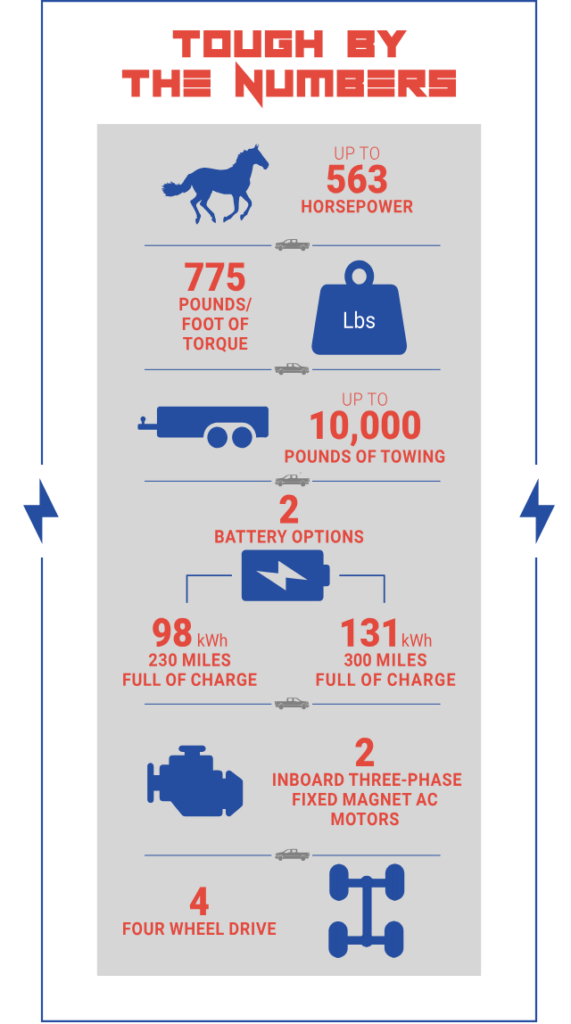

To accommodate that size, EV batteries typically cover most of the underside of the vehicle. And the Lightning is no different. It comes with two battery options: a 98 kWh model that gives a targeted 230 miles on a full charge, and a 131 kWh version offering a targeted 300 miles.

Both run from wheel to wheel along the bottom and weigh up to 1,800 pounds. Zhang and her team provided extra protection by creating a metal “exostructure” to house the battery and adding metal skid plates to the underbody.

One design change from traditional F-150s that Lightning owners will be able to feel can be found at the back axle. And this one leans more into the pickup’s new EV identity, and less into traditional truck toughness.

Typical pickups feature a live beam axle at the rear, a dependent suspension system where the two rear wheels are directly connected, and shocks from bumps are distributed to both sides. Those axles are normally paired with leaf springs. It’s a sturdy and relatively cheap combination that has been in use for years.

Lightning, however, features a rear independent suspension, allowing each rear wheel to react to bumps in the road differently and giving a smoother ride. Ford has added coil springs to the setup. It’s a more expensive choice made by Zhang and her team.

The reasoning behind it has to do with one of the major differences between Lightning and its F-150 predecessors: the location of motors on both the front and rear axle. That arrangement gives the truck the “tough” requirement of all-wheel drive, but necessitates rear independent suspension/coil springs setup.

“If we were simply providing front-wheel drive, where the back axle was simply following along behind the front, then we wouldn’t need this,” Zhang said. “Having a motor on the back axle, however, almost pushes us toward independent suspension.

“We also went this route to underscore one of the benefits of the electric vehicle experience: the quiet ride. To us, this felt like this was another way of providing that smooth, pleasant driving experience.”

Frunk

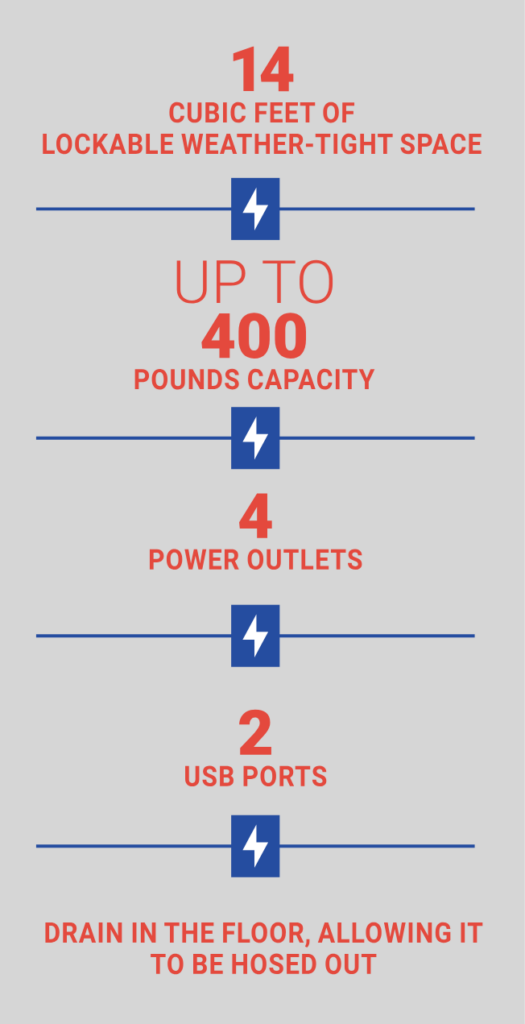

Oddly enough, the Lightning design feature that may be getting the most attention is, for lack of a better phrase, just a lot of empty space. With its dual motors affixed to the front and rear axles, there’s no longer anything “under the hood” on the pickup.

Zhang and Ford have embraced that space with their “Mega Power Frunk.” Now, to those old enough to have driven Volkswagen Beetles produced during most of the 20th century or, more recently, Tesla’s Model S, the front trunk isn’t anything new.

But the size of the compartment Lightning provides in this space is rare enough to make its frunk the subject of a slew of YouTube review videos. In one of those, produced last year by Roadshow, narrator Craig Cole said: “I know it sounds silly, but this is actually one of the truck’s coolest features …”

For her part, Zhang welcomes the interest the frunk has generated and noted that test groups played a large role in what customers will find in the Lightning.

“They told us, ‘If you put a drain in the bottom, I could put drinks in there,’ or, ‘I need an outlet here for when I’m working,’” she said. “But when we introduced the idea of a divider, a cargo management system, in there, they hated it. They wanted to be able to do whatever they wanted with it.

“They’d say, ‘Give me every ounce of space that you can give me in there and I will find something to do with it.’”

Manufacturing Lightning

Zhang’s introduction to the auto plant environment began long before she arrived for her first day as a Ford employee.

Her father worked for the automaker after the family moved to Michigan from West Lafayette. His practice of occasionally bringing his daughter to work helped draw her toward engineering and the auto industry.

“That’s how I got introduced to Ford for the first time, probably when I was 14 or 15 years old,” she said. “We would go to the plants and see what it was like. His work was centered around reducing the scrap rate of glass—improving the system to reduce losses during production.

“It was interesting to be in that environment and see, ‘Wow, this is what engineers do.’ It’s kind of what stirred my initial curiosity.”

Years later, when her role with the Lightning called on her to help design a state-of-the-art production facility, she had even more familiarity to draw on.

Ford’s Dearborn Assembly Plant cranked out cars from 1918 to 2004 before the bulk of the facility was eventually torn down. Zhang was among the hundreds of workers who built cars there in its closing years. That site is now home to the new plant she helped create for the Lightning.

“I actually used to work there when it was still a Mustang plant… that was in the body shop,” she recalled. That experience came from her participation in Ford’s College Graduate program—an in-house offering that exposed her to all facets of the automaker’s operation.

What she and Ford officials eventually came up with years later is the Rouge Electric Vehicle Center, a 506,000 square foot space—11.5 acres’ worth—mixing tried and true aspects of the traditional F-150 production with the latest technologies to produce the Lightning.

On the production floor, one of the first things you notice is the lack of clutter compared to a traditional plant. There is open space here and plenty of natural light. Conveyor belts and skillets have given way to automated guided vehicles that move components around by following a magnetic track in the floor.

“We had over 70 different items that our advanced manufacturing team put together to incorporate into the plant,” said Skaggs, who runs the plant’s day-to-day operations. “And they’re really doing two things for us: making us more efficient and improving our communication.”

At workstations spaced out across the massive floor, iPads are everywhere. They’ve allowed the plant to digitize countless processes that were still done via paper until just recently—shortening the feedback loop for those operations and moving tasks along more quickly.

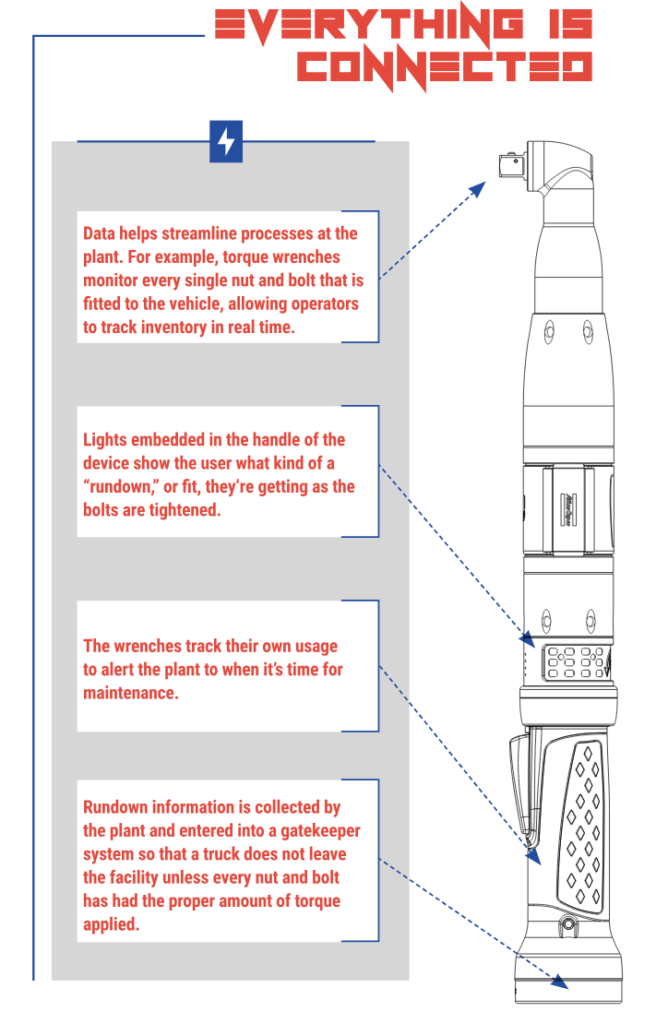

But it’s not just the speed of the data collected, it’s also the amount and kinds of data that can now be made instantly available to plant officials to streamline the processes.

An example is the pneumatic torque wrenches being used to tighten nuts, bolts and screws all over the Lightning. During operation, the “guns” track a host of things.

“Our Assembly Information Stations know how many bolts need to be shot, and it knows because it sees which specific truck is docked,” Skaggs said during a January tour. “It knows what the torque for each nut and bolt is and it knows which employee is doing the work.”

Zhang and her team used the blank slate of a new plant as an opportunity to test new technologies. An example is the headlamp aiming station, a standard part of any auto plant.

“We opted to put in two separate stations, one with the traditional equipment we’ve used for years, and a second one featuring new technology that had expected benefits,” Zhang said. “We wanted to make sure we had this new tech in-house, but also wanted to build in a safety net with the older equipment to ensure we can produce the vehicles while training the new station.”

The success of the new technology has Ford implementing it at both Rouge Electric Vehicle Center stations, as well as eyeing its use in other plants. And the addition of a second aiming station at the home of the Lightning now seems prescient, as demand for the electric pickup has soared.

All the automation and new technology has resulted in a new plant capable of producing an F-150 Lightning in roughly the same time it takes to make a regular F-150.

“From the moment they lay the pan down and begin sending it through the body shop, to screwing everything together, to going through the paint shop where it gets that beautiful finish,” Skaggs said, “you’re talking just a little over 24 hours.”

Selling Lightning

Many Michigan Engineering alumni were probably still hopeful and tuned in when—just over 3 minutes into Michigan’s national championship playoff with Georgia on New Year’s Eve—Ford hit you with its first Lightning ad of the night.

“We had to show the Lightning was durable and capable, that it can do everything your current truck can do, plus even more.”

Linda Zhang, Lightning’s Chief Engineer

Two commercial breaks later, when you were getting a sinking feeling about the Wolverines’ chances, they hit you with another. Each ad, though different, spent time focused on one of the pickup’s more intriguing features: its ability to act as a power source.

There’s the Lightning at a work site, providing the electricity for power tools. There it is again powering lights at a campsite.

But most eye-catching is the pickup shown providing the power needed to run a house in the event of an outage. It’s become a major talking point for the vehicle—perhaps offering a new version of what “tough” should mean in the EV era.

Like everything major automakers do, the imagery emphasized in marketing campaigns resulted from extensive market research. It’s another area where Zhang’s education choices helped put her in the middle of nearly every decision made on the Lightning’s journey.

After joining Ford in 1996, she pursued opportunities to diversify her expertise, jumping between engineering, manufacturing and finance. Her in-house experiences fed her interests in branching out.

“I wanted to learn more—I was getting fairly strong on the technical side of the business, but wanted to understand the business side of things,” Zhang said. “That was something I never really dealt with much during my undergraduate studies, but I recognized it was super-important.

“When I got to Ford, I was in the College Graduate program, which lets you rotate into new areas every three to six months to get different experiences. And what I learned was there was a lot I didn’t know.”

Seeking to bolster her understanding of the industry, Zhang spent eight years trekking out to Ann Arbor from Metro Detroit in pursuit of her Ross MBA. It gave her a toolkit she could dip into during the Lightning design process when analyzing the cost/benefits of features like the rear independent suspension.

But Ross also made clear that it’s not just how you build your project, but how you present it to the public. Zhang recalled early tests where subjects were asked to illustrate their idea of a gas truck driver versus an EV truck driver.

“Some of the things we saw were people saying, ‘Well, you know, the gas truck driver would be drinking beer,’ and having a big dog, while they pictured EV truck drivers drinking a martini and having a little dog,” she said. “There was a lot of skepticism and mindsets we had to overcome.”

Those kinds of stereotypes and tropes help explain the strategy behind Ford’s advertising choices.

“We really had to change hearts and minds,” she said. “We had to show the Lightning was durable and capable, that it can do everything your current truck can do, plus even more.”

What they’ve done seems to be working. Early in 2021, Ford planned to produce 75,000 to 80,000 Lightning vehicles per year. But as the months clicked by, reservations for the pickups climbed. By July, there were 100,000. Four months later, that number was 160,000. And in January that number passed the 200,000 mark, forcing Ford to announce it would double its annual production estimate to 150,000.

“I mean, the Lightning has just captured the imagination of a lot of people and it shows up in our data,” Krebs said in February. “We’re seeing people shopping for it and it’s not even out yet”

Electrification’s larger picture

U-M grads dot the automotive landscape around the world, particularly down the road from Ann Arbor in Detroit. Throughout the larger industry ecosystem, U-M alumni are involved in the move to electrification—quite possibly the biggest transition for automakers since adoption of assembly line production.

“It’s not surprising to me, but honestly it’s really great,” Zhang said. “U-M has always been a cornerstone, in a way, for providing talent for the industry. I’m on Ford’s recruiting team for U-M, partly because it’s such a great engineering school, but it also has a great business school and sciences.”

Electrification, however, means more than just the vehicles themselves. A whole world of issues are in play right now that will determine how quickly and effectively we move away from fossil fuel-based transportation.

Across North Campus, researchers and students investigate everything from extending battery life and boosting charging performance, to recycling EV materials and helping train the workforce for this new technology.

“Our university is at an EV inflection point, as are the auto industry and society at large as we prepare for major EV innovations,” said Alec D. Gallimore, the Robert J. Vlasic Dean of Engineering, Richard F. and Eleanor A. Towner Professor, Arthur F. Thurnau Professor, and professor of aerospace engineering. “We have faculty working to provide insight, guidance and thought leadership—before EVs become a majority of production models and society’s primary vehicle fleet.”

On an early morning in March, Gallimore and Mingyan Liu, the Peter and Evelyn Fuss Chair of Electrical and Computer Engineering, got a ride-along in a Lightning with Zhang behind the wheel, giving them an up-close look at where Zhang’s Michigan Engineering journey has taken her so far.

“We believe engineers must have technical aptitude. But they also must have a deep appreciation for how their field integrates with others and a well-honed ability to evaluate its impact on the world from multiple perspectives,” Gallimore said. “Linda is a great example of that people-first mindset in action.”