Her fight for your rights

Could censorship end the internet as we know it? Not if Roya Ensafi can help it.

Written by:

Story by Julie Halpert.

On a cold February day, Roya Ensafi is dressed casually in boots, jeans and a sweater. She’s hastily cleaning up her office following a marathon work session. There are reams of notes, along with an empty Cheetos bag, a Minute Maid juice bottle, coffee cups and a banana strewn on her desk. This is the place where in 2018, she founded the Censored Planet lab and, in the years since, has built it into a major player in the global computing community.

Between 2018 and 2020, Censored Planet uncovered a plan by the Kazakhstan government to monitor its citizens’ internet use and worked with Google and Mozilla to foil it. It monitored Saudi Arabia’s increased internet censorship in the wake of the killing of journalist Jamal Khashoggi. It uncovered key details about Sovereign Runet, a sweeping Russian censorship scheme that essentially lays a blueprint for countries with decentralized internet infrastructure (including the United States) to monitor and censor their citizens. And it worked with the Wall Street Journal to examine increased U.S. blocking of Hong Kong websites as the country adopts policies that align with mainland China.

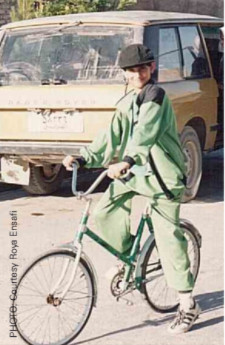

But Ensafi, who left her home country of Iran in 2008 and has never returned, has paid dearly for her success. As tears begin to stream down her face, she says, “I made a major sacrifice for this work.”

Ensafi left her home country in 2008 to pursue better opportunities in the U.S., buying credit cards on the Iranian black market to pay her school application fees. It was not an easy choice, as she knew she might never be able to return to her home country again. But she felt it was the only option.

Ensafi is grateful to have received a free undergraduate education in Iran, but she knew she couldn’t thrive in its gender-segregated system. There were vast restrictions on information from both the Iranian government and from the West, which blocks Iranians from accessing many educational resources.

“The world decides for you that you can’t reach your potential. I could not accept that,” she said. “Coming to the U.S. was my own dream. It’s a place of unparalleled freedom and opportunity and of course, the center of global science.”

The plethora of plants that line the ceiling and walls of her office date from the early, difficult days when she first arrived here. They became crucial companions when she left Iran to attend graduate school.

“I didn’t have anybody,” she said. “I basically had to have people to talk to and plants are the best.”

The greenery has become a central part of her work environment, though these days it takes on a different meaning. The plants surround an oriental rug and a comfy couch, creating a feel as cozy as a living room. It seems appropriate, since this has become a second home to her. She ensures her colleagues feel welcome by the food she often prepares.

Ensafi is grateful to her colleagues; aware that she has no family in the U.S., they have helped to fill that void and have become part of her community. She says cooking them food of her homeland is therapeutic and reminds her of her childhood. “Listening to traditional music while I am cooking creates a very calm and safe atmosphere for me,” she says.

“I love cooking and baking. Being a female and having cakes in your office is not a bad thing,” she says with a smile.

Ram Sundara Raman, a PhD student working on Censored Planet, agrees. “She cooks some amazing Persian food. I’ve had it several times.”

Ensafi brings a unique, non-Western vantage point to her pioneering work revealing internet censorship around the world. Her research shows that censorship doesn’t just happen from governments like Iran, but in unexpected ways and places, including the U.S. and Europe.

“Censorship can happen here too,” she says. Her mission is particularly important now, since she says censorship is proliferating, as it has become much less expensive to deploy filtering technologies that block internet access.

She explains that technical developments and policy changes in the U.S., such as the repeal of net neutrality, create an environment in which internet service providers can easily interfere with a citizen’s traffic. “This is an architecture for greater censorship and we should all be worried about heading down a slippery slope,” she says.

Ensafi was motivated to enter her area of study growing up in a country that routinely experienced censorship. “I was a student and avid swimmer and couldn’t watch the Olympics,” Ensafi said.

But this wasn’t due to the Iranian government blocking access. It was because Iran was the subject of geo-blocking, a phenomenon in which server operators prioritize the regions that are likely to generate the most advertising revenue, siphoning off bandwidth from other regions—like Iran—that may provide less revenue.

Ensafi initially planned to work on theoretical security research problems like discovering security bugs by formally verifying network protocols. But the first years of her PhD program coincided with momentous events: Iran’s Green Revolution—where protests erupted contesting the presidential election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad—and the Arab Spring.

She saw how internet connectivity plays a key role in supporting grassroots movements and felt a calling toward a project that could be deployed for the greater good, more “than just publishing a paper.”

She discovered that there were significant obstacles to learning about censorship, which has traditionally relied on volunteers within the country, usually activists, to collect this type of data. She felt there must be a way to monitor censorship without potentially putting people in danger.

“You shouldn’t ask volunteers to help when there’s a politically sensitive situation happening because they could be targeted by the government,” she said.

This is an architecture for greater censorship and we should all be worried about heading down a slippery slope”

Ensafi pondered how her research could be applied to the problem and assist in the remote collection of data on censorship. She saw the need to develop a rigorous system for acquiring objective, reliable data that would be both comprehensive and global and that wouldn’t require volunteers. What started as a germ of an idea during the time of Arab Spring continued throughout her academic trajectory.

“I didn’t give up on it,” she said. She discussed it with her adviser, Jed Crandall, at the University of New Mexico, then continued to work on the technical details when she headed to the University of California, Berkeley in June 2014 and then Princeton in January 2015.

Her idea eventually became Censored Planet, which relies on advanced network side channels to collect data from thousands of vantage points to determine when access to websites is being blocked across the globe.

Running from specially configured computers outside the country being studied, Censored Planet uses a variety of tools to scour the internet and find publicly available servers that can serve as “reflectors”—automated vantage points inside the country of interest. A good reflector is generally a public server that’s not owned by an individual—this ensures that there’s virtually no chance of it being traced back to any one person. In addition, it must follow current internet protocol, and be reliable and stable enough to be used for regularly monitoring censorship. Reflectors are often located at universities or run by the internet service providers that make up the backbone of the internet.

Once the system has established a network of reflectors—which can be done in a matter of hours—a measurement tool generates traffic which is directed at a list of selected web addresses. By analyzing the information that comes back, the tools can determine whether and how those addresses are being blocked.

“We designed a clever technique to be able to gain information from the path,” Ensafi said.

The goal is to ensure a more connected internet where all users have equal access to the information.

One of Censored Planet’s first successes was in Kazakhstan, where Ensafi’s research uncovered a “Man in the Middle” situation. Activists told her that the Kazakhstan government was sending text messages to the people in the region asking them to install a root certificate into all their devices that would allow the Kazakhstan government to intercept, decrypt and re-encrypt any traffic passing through their systems. This would then enable the government to read encrypted emails and social communications between citizens.

Censored Planet had tools and measurements in place to collect data from 6,000 vantage points in Kazakhstan and found that this interception was happening at around 600 of them. “We’re using the simple properties of the network to be able to gain information about deployed censorship,” she said.

Ensafi led a team to build a comprehensive report of the results, which was published and shared with the tech community, including Mozilla and Google Chrome, asking them to act. Chrome and Mozilla immediately responded, not only publicly condemning the network interception, but also pushing changes to all users’ browsers that prevented the government of Kazakhstan from continuing the practice.

Ensafi says that by providing data-driven reports on the details of the attack, she’s encouraging transparency about how the internet is operated. “We’re outing these harmful practices in a very positive, friendly, cooperative way.” She says public outcry is a huge positive motivator and she’s found that once the problem has been revealed, the response from operators has been positive.

Atul Prakash, a professor of computer science and engineering who shares a security lab with Ensafi, says Censored Planet played a crucial role in removing censorship in Kazakhstan.

“The government admitted the practice and stopped it, while companies like Google started deploying defense measures,” he said. “That’s what I admire about Ensafi. The problems she studies lead to active changes.”

Life, Engineered

She’s been called the hidden hand in the movement that enabled smartphones, PCs and the very fabric of Silicon Valley.

More stories from

The Michigan Engineer magazine

Ram Sundara Raman is one of three PhD students working on Censored Planet. When applying to graduate schools, he was drawn to the University of Michigan because of Ensafi’s research. “She’s really passionate about her work and believes it’s important to do that work,” he said. He has been working in the lab since August 2018. As a computer science and engineering student who completed an internship on internet measurement in 2017, he saw her lab as creating synergy in his area of study.

Raman is excited to be charting such new territory and working on something that hasn’t been undertaken before. And he says Ensafi has been an incredible mentor.

“She works through the problem with me if I’m stuck on it and helps me with the next steps to take,” he said. “She doesn’t just focus on the work, she provides suggestions on how to be a better researcher.”

Prakash says Ensafi is a magnet for students who are attracted to her research and that she goes to great lengths to recruit new students to the lab. “She’s a great citizen of the department.”

Ensafi is particularly gratified by her interactions with students. In Fall 2019, she taught the first class ever offered at U-M on privacy and censorship technology. In Fall 2020, she taught her first undergraduate class, an Introduction to Security class for 350 students. She’s fueled by their excitement and enthusiasm.

“You feel so much more responsible to be prepared,” she says, “because they’re genuinely grasping what you’re saying. You want to be the best you can be.”

Being a female in the male-dominated world of security brings significant challenges. “I have to go through a lot of steps to gain respect,” she says.

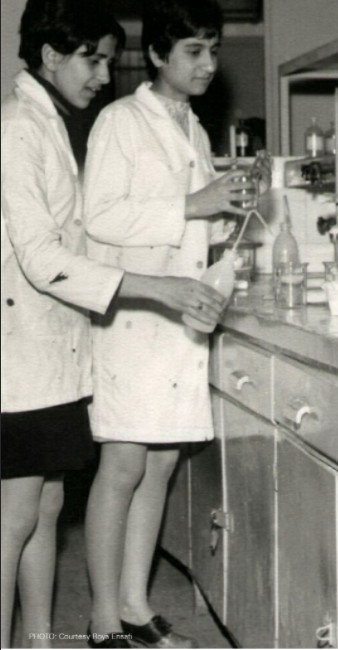

Ensafi’s mother, a chemistry teacher, continues to be an inspiration. Her mother’s dream was to earn a PhD and become a professor as well. But that dream came to a halt when she became pregnant the last year of her undergraduate education and began to start a family.

“She ended up with five kids and four doctorates,” Ensafi joked. “She told me that it’s okay to be emotional and still lead. You don’t need to be masculine or pretend to be strong emotionally to get things done.”

Ensafi has taken that advice to heart and tries to model this behavior. She doesn’t hesitate to show her emotion with students and colleagues when she’s feeling it. Incorporating female sensitivity to a fully male-dominated world, “that is not unprofessional. There’s a beauty in that,” she said. She urges her female colleagues to be their authentic selves instead of trying to mask their feminine characteristics.

She makes it a point to encourage more women to enter the male- dominated field of security and strives to be a role model for the many women who she says are eager to work with her. She believes there’s a shortage of females since they’re concerned about failing and “security requires you to fail a lot more.” She believes women can make valuable contributions to the complex field of security and that they provide a crucial diversity of thought.

“If you look at security problems, females are in a better position to solve them. They juggle so many different things,” she said. She’s observed that female researchers tend to approach problems with a broad perspective, rather than immediately pushing down one path to a solution. “In security, this helps make sure you don’t overlook vulnerabilities or miss an easier way to defend a system.”

The ability to multitask also allows women to successfully address several problems at once, a key asset, she said. She started Women in Security Research (WISER) last year as a way to further her goal to bring women into the field. She’s proud of the balance on her team, which includes five females and three males.

Though the demands of her job juggling many different types of projects are constant, Ensafi protects her time away from work. One day of the weekend, she takes a break from work and social media. “I completely sign off. I’m just not accessible.”

You don’t need to be masculine or pretend to be strong emotionally to get things done.”

While she’s clearly a leader in her field, Ensafi isn’t interested in becoming a figurehead and strongly resists attempts to portray her as a Middle Easterner fighting for internet freedom in her home region. She believes that censorship is a global phenomenon and that citizens everywhere should be united in fighting against threats to internet freedom.

“I want to be known for my work as a scientist, not for my life story,” she said. “Framing censorship as a product of specific governments detracts from the grim reality of its international spread.”

Pointing out that she’s spent over a decade researching and speaking about censorship through that lens, her solution to defending against global censorship is to use measurement to bring transparency “and to help improve censorship-resistance tools that work everywhere.”

Despite the atmosphere that forced her to leave Iran forever, she looks back on her native country fondly. “There are so many things that I love and miss about Iran,” she said. She marvels at its unique architecture and historical sites. “I miss walking through the streets of Yazd and Isfahan looking at the old houses and thinking about the people who used to live there.”

“Even now that I’m in the U.S., I have a love for Iran and I try my best to shed light on its beauty.”