A face that looks like mine

Engineering is a field that remains stubbornly white and male. NextProf is designed to change that.

Engineering is a field that remains stubbornly white and male. NextProf is designed to change that.

Imagine what story the 13 pictures hanging on the fourth floor wall of the Robert H. Lurie Engineering Center tell.

Thirteen portraits of 13 faces. Each one, a dean who has led the University of Michigan’s College of Engineering at one stage, starting from its creation 165 years ago to modern times.

It could read as a story of achievement – of humble beginnings for a school that has grown and risen to become a college of international prominence. It could even be a story of changing fashion styles over more than a century and a half.

Look a bit closer at what’s on the wall. Thirteen men. More specifically, 13 white men.

Now imagine what the story might be to a slightly younger version of Naomi Mburu. Her parents were immigrants from Nigeria. She’s currently a PhD student at Oxford in nuclear engineering. Would the wall serve as an invitation to join the field?

“Growing up in Baltimore, I didn’t know any engineers. It just wasn’t a common career in the area I was living in,” she said. “My father even had a degree in engineering but, as an immigrant, he was never able to get a job in the field. So, early on, I never really thought about being in engineering. ”

The faces we see often act as a subconscious indicator of whether we belong. Engineering, to many, can be a forbidding room filled with unfamiliar faces. For all its glorious accomplishments, the field, both in academia and the commercial sector, remains stubbornly monochromatic and male.

Lack of diversity among faculty is a problem that NextProf, a program at Michigan Engineering, has been striving to counter since 2012. Created to bolster the number of underrepresented minority groups, it eventually expanded to address women as well.

Twice a year, NextProf draws graduate students from U-M and institutions around the country, connecting them with accomplished engineering professors. It’s meant to highlight the benefits of academic positions and offer insights on how to get them. Mburu is among those NextProf hopes to influence.

By increasing diversity among the ranks of professors, U-M officials hope engineering will become a more welcoming field for those who fall outside the white male demographic.

“Diverse teams, if managed properly, yield superior outcomes,” said Alec D. Gallimore, the Robert J. Vlasic Dean of Engineering at U-M and a NextProf co-founder. “What we’re trying to do with NextProf is diversify the engineering field. By having a more diverse collection of professors, we believe we will have more diverse and, frankly, better overall engineering students.”

Nationally, however, it’s an effort that has proven every bit as difficult as you would imagine.

“In recent years, we’ve seen only a slow increase in women nationally,” said Robert Scott, director of diversity initiatives for Michigan Engineering, who has shepherded NextProf since inception. “And the percentage of underrepresented minorities in faculty positions is on a flatline that’s been in place for 15 or 20 years.”

U-M has been joined in its efforts recently* by two more engineering heavyweights: the University of California, Berkeley and the Georgia Institute of Technology. It’s a partnership with great potential due to the institutions’ reach and prominence.

But the challenge remains – like some immovable object – begging the question: Can engineering fix itself?

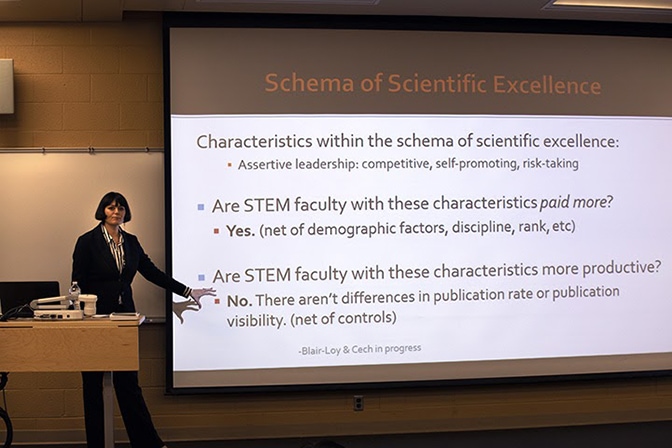

“It’s not a single problem – if it was, we’d have solved it already,” says Erin Cech, a U-M associate professor of sociology, addressing engineering’s lack of diversity among faculty. Her research tackles inequality in STEM education. “Some of this is structural. Some of this is about who has access to the kind of K-12 education that will give them the college prerequisites to be competitive as undergraduates.

“If you want to go on to graduate school, you have to have come from the right kind of undergraduate program. And if you want to wind up in a tenure-track position, you typically have to come out of a particular kind of graduate program.

“So there are structural constraints in terms of who has what resources, built around historical patterns of oppression that operate not only for gender, but race and class as well.”

So many of the factors that Cech listed that work against underrepresented minorities worked against Alexander Alvara.

Among them: one of eight siblings. Never knew his father while his mother worked multiple jobs to provide. Grew up in a host of poor neighborhoods – California’s Los Angeles and Riverside counties mostly, places with more than their share of gangs and drugs. Occasional stretches of homelessness.

“We’d barely have enough money to move into a place and then, you know, one little setback…,” Alvara said. “We’d get kicked out, and everyone would have to go and live with different people, family or friends.

“Then, when we could, we’d start over somewhere else and the cycle would inevitably begin again.”

Along the way, friends wound up in jail. Another suffered a far worse fate, dying from a drug overdose.

Despite these challenges, Alvara earned three bachelor’s degrees in engineering from the University of California, Irvine. He’s an example of the talent that can be left untapped in minority groups. He attended U-M Engineering’s NextProf Pathfinder program in September in Ann Arbor.

“There’s a lot to learn here – things I didn’t know,” he said during a break in the program. “Like research is important, but so is service in teaching. I always thought you’re a wonderful researcher and, one day, you become a faculty member – you just apply.

“But it’s a little more complicated than that, I’m learning.”

In a few years, Alvara will wrap up work on his PhD in mechanical engineering. It’s a great story of obstacles overcome, but it fails to take into account one of the biggest factors working against Alvara – his Latino heritage.

Hispanics account for only 11% of bachelor’s degrees awarded in engineering in 2017, and just over 6% of doctoral degrees.

There’s an open bar and plenty of snacks on hand – egg rolls, mini-meatballs, tiny pizzas – as graduate students in engineering start rolling in to a medium-sized conference room at the Kensington Hotel.

It’s 5 p.m. on Sept. 18, the opening night mixer for NextProf Pathfinder, and the mixing begins immediately. Conversations begin in earnest about hometowns, universities, areas of research. It’s a purposely diverse group, but there is plenty to bond over. Everyone here has already achieved some level of academic success. There’s no dumbing down of the subject matter. It’s freeing.

Pathfinder targets those in the first or second year of their PhD studies. Over the next three days, the 33 on hand will hear from roughly 20 current U-M engineering faculty members.

Subjects range from “Life in Academia” and “How to Get the Most Out of Your Lab” to “Time Management in the World of Research.”

Alvara is among those in attendance. So is Mburu. One of the first people they’ll hear from is Lola Eniola-Adefeso, a U-M professor of chemical engineering and a University Diversity and Social Transformation Professor. Her talk is direct, punctuated by key statistics. She exudes a level of confidence she says she didn’t always possess.

Eniola-Adefeso’s career path split on the thinnest of margins. Her first exam in chemical engineering at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County was a “complete failure.” That result, she believed at the time, told her all she needed to know about her future as an engineer.

“I was not even on the chart,” she recalled. “I remember going in to my professor the next morning and saying, “Hey, I’m just letting you know that I’m going to go and change

my major. Clearly, I can’t be an engineer if I can’t even pass this test.”

That pivotal moment for Eniola-Adefeso hinged on the person sitting across from her. Julia Ross, a UMBC professor at the time who is now Dean of Engineering at Virginia Tech, stopped Eniola-Adefeso in her tracks.

“She just laughed and said, “Sure you can do this. You’ve got to be an engineer,’” Eniola-Adefeso recalled.

But there is a disturbing aspect to the tale as well, one that’s not lost on the teller. It’s one of the reasons she’s part of the NextProf program.

“I don’t know that I would have ever gone to have that conversation if she was a man,” Eniola-Adefeso said.

In 2017, women made up less than 13 percent of the engineering workforce, up only slightly from 10% in 2003. There is a greater loss behind those statistics than one might realize.

“Women who leave engineering tend to have a higher GPA on average than the men who stay,” Cech explains. “So it’s not an issue of them not being able to do it, or being unable to perform at the same level as men. But there is a sense of not feeling that they belong in that space.”

Eniola-Adefeso is determined to be the same kind of mentor Ross was for her.

“I did research with her in my graduate career when Julia said to me, ‘You should consider being a faculty member,’” Eniola-Adefeso told her audience. “I did not blink. Why? I knew I could be a faculty member because I’d seen someone that looks like me be a faculty member.”

There is a responsibility that comes with being among the first, or being a rarity in your field or one of only a handful. People often look to you to be the spokesperson for an entire demographic group. It can be exhausting.

Yet here Austin Wadle sits, answering any and all questions and serving as a mentor during the Pathfinder program.

“I’m an environmental engineer, as far as what’s most relevant to this program,” Wadle said. “But I’m also transgender. I use the they, them pronouns and I’m non-binary.

“Every day I sort of move through a world in which people like me weren’t ever really imagined. “

Focus solely on Wadle’s gender and you’ll miss quite a bit. The Miami native attended middle and high schools centered on the arts, emerging as a classically trained tenor. The liberal arts college they attended as an undergrad didn’t have an engineering program.

Now Wadle is one year into a doctoral program at Duke University focusing on environmental health engineering. It’s not the typical background of most of the people at Pathfinder, but variety in math and science is a good thing.

To back that up, Wadle cites a 2011 research paper titled “Expanding Underrepresented Minority Participation: America’s Science and Technology Talent at the Crossroads.” The paper, produced by the National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering and Institute of Medicine, tackles what’s at stake for the U.S.

“Yet, while our (science and engineering) capability is as strong as ever, the dominance of the United States in these fields has lessened as the rest of the world has invested in and grown their research and education capacities,” the report reads. “…America faces a demographic challenge with regard to its science and engineering workforce: minorities are seriously underrepresented…yet they are also the most rapidly growing segment of the population.”

Expanding participation in science and engineering, they argued, is key for three reasons:

Wadle, whose research focuses on mercury biogeochemistry, sees efforts being made by the federal government to broaden STEM participation, but notes even those are bound by a traditional idea of what underrepresented minority groups mean.

“One of the really fortunate things about Pathfinder is, because it’s sort of run independently through the University of Michigan, they are able to tackle other diversity issues, including first-generation status, disability status…,” they said. “Also queer students, including students like myself, who are transgender.

“The fact that (diversity efforts are) often determined by federal dollars does limit a lot of diversity program impacts.”

Those limits, along with societal practices that push children into outdated gender roles, are what Wadle refers to as “filters.”

“Part of the point of NextProf is removing those filters so that more people like me and our other participants can make it through to the faculty levels so we have the power and agency to remove those filters at every institution we’re at.”

Given the number of advanced degrees in the room, it’s hard to imagine that impostor syndrome would find much traction among the crowd at NextProf Nexus in Atlanta. And yet it’s a subject that comes up repeatedly.

Defined as a “persistent inability to believe that one’s success is deserved or has been legitimately achieved as a result of one’s own efforts or skills,” impostor syndrome is common among underrepresented minorities in academia.

So it’s both comfort and inspiration to many on hand Oct. 3 when Rafael Bras takes the stage. The provost here at Georgia Tech, he speaks quietly and evenly, with the accent of his native Puerto Rico. And the 72 graduate students in his audience hang on every word.

He tells them of his youth on the island and the limits his language and lower-middle class upbringing seemed to place on what he thought he was capable of. It’s a powerful lesson in what’s possible.

“A lot of opportunities are the result of chance, but a lot of opportunities do not occur unless you take action to make sure that those opportunities could occur,” Bras says. “It’s that play between chance and necessity that dictates a lot of life.”

Georgia Tech is co-hosting Nexus – the NextProf’s program for 3rd- to 5th-year PhD students and recent doctoral graduates – for the first time, partnering with U-M and Berkeley. The three-day itinerary is crammed with speakers who have been through situations audience members are facing now.

Bras’ own path took him from his island home to the mainland and MIT. He’d been accepted at other prestigious institutions like Cornell and Georgia Tech – all without getting particularly high marks on the SAT.

“I got in because somebody in those institutions decided that I was worth the risk,” he said. “And, yes, somebody in those institutions decided that they wanted someone from Puerto Rico in there. And I’m not ashamed of that at all. I think it’s absolutely great.”

Near the end of his NextProf talk, Bras shares an anecdote from his past. It’s one that highlights the survival skills he wants graduate students to develop as underrepresented minorities in engineering.

At 32, Bras became director of an MIT lab – just after receiving tenure. He had about 20 people working under him, every one older. During his first faculty meeting, a colleague, speaking absentmindedly, said of Bras: “Well, we know how you got here.”

“I have to say, I’m pretty quick to respond most of the time, but this took me by surprise,” he said. “I stayed quiet for a little while, then I looked at him and said ‘Look, it doesn’t matter how I got here. I’m your boss.’

“That was the end of that. That level of self-awareness and self-confidence that you need to develop is so important.”

There are a host of reasons why graduate students veer off the path to academia, from the personal to the financial.

Jessica Eisma is on the verge of completing her PhD in civil engineering at Purdue University and is eyeing potential faculty positions – an upcoming decision that drew her to Nexus. Given the opportunity to question panel members, Eisma takes the microphone and asks how universities support female faculty with families.

Many female professors choose to either delay having children or forgo the option altogether in order to achieve tenure. For Eisma and other women in attendance, it’s a question of whether academia is compatible with wanting to have children earlier.

The issue is complex, but on stage is Susan Margulies, chair of Georgia Tech and Emory University’s Department of Biomedical Engineering. She’s been described as a “world leader in the biomechanics of head injury in infants,” but there are other factors that make her a perfect example of what’s possible in the right environment.

“I met my husband during freshman year in chemistry lab, so that means every one of my moves has been a dual career move…,” Marguiles tells the audience. “I had our first child when I was at a point in my postdoc at the Mayo Clinic School of Medicine. Our second child was actually born my first month as an assistant professor…

“It’s about being you and finding the best place for you.”

Despite Cech’s position as a sociologist, she can speak to other issues that derail women from academia in engineering from personal experience. In 2005, she had two paths before her after earning a pair of bachelor’s degrees from Montana State University in Bozeman – one in electrical engineering and another in sociology.

Engineering had a special pull because her grandmother was blind and Cech hoped to get involved with assistive technologies to help improve accessibility and equality. She would quiz her professors on possible applications, but the answers were never what she was looking for.

Other factors pushed her away from engineering. It was hard to avoid reminders that the field was male-dominated and there were few engineers who could understand her situation.

“As a student, I would go to professors’ office hours and I could tell they didn’t necessarily expect me to have a competent question to ask,” Cech said. “I interned at a public utility, designing power grids for subdivisions. I’d have to go to construction sites and wrangle contractors to do what was needed. The sexism on construction sites was a total nightmare.

“I guess I didn’t expect to find someone who looked just like me in engineering, but I really wanted somebody who believed in my capabilities. It’s part of that thing that makes you ask, ‘Do I belong here?’”

For still others, more immediate considerations rule the day. As Shelbie Prater prepared to leave Michigan in 2018 with a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering, she spent several weeks considering a doctorate.

But when push came to shove, circumstances made the call for her. She had grown up in a single-parent household, one of the oldest of eight children. So the need to support her family was top of mind.

“Frankly, first was just the money issue – I needed to start having a reliable source of income as soon as possible,” said Prater, who now works in Chicago at KPMG, the global accounting organization. “I felt that I had a calling when I first got to the University of Michigan to be a leader in this space, a leader for my peers and for my siblings. Those were two conflicting things, as it turned out.”

It didn’t take long for Patricia Yang to take notice after arriving in the U.S. from Taiwan for graduate school at Georgia Tech in 2012.

“When I walked into the graduate office, I realized, ‘I’m the only female,’” she recalled. “Later, I realized that I was the only one using the ladies restroom on my floor.”

Yang is now an award-winning post-doc researching fluid mechanics, and she participated in the Nexus program. She is the kind of engineer Gallimore had hoped to reach when he started NextProf in 2012. Her story is not unfamiliar to him.

“We had a retreat for the faculty, the leadership of the college, chairs, associates…,” said Gallimore, who in addition to dean is the Richard F. and Eleanor A. Towner Professor and an Arthur F. Thurnau Professor. “We had a break. And after the break, the women chairs and associate deans celebrated because there was a line to the ladies room. And that had never happened before at a retreat.”

On its own, U-M has had success in boosting female representation in engineering. In 2019, half of the College’s leadership positions were filled by women. But nationally, diversity in the field for underrepresented minorities continues to be a stubborn metric.

Gallimore is aware of all that works against what NextProf is trying to do. It’s one of the reasons that U-M aims to increase diversity at more than one stage. Where NextProf targets graduate students, programs like the Michigan Engineering Zone, the University’s Detroit-based robotics program, aim to get high schoolers interested in science and math.

Getting more students into such activities early on creates a larger potential pool of candidates to join engineering’s academic ranks.

“It’s an enormous endeavor,” he said. “We’re trying to harness the incredible engine we have for bringing students into the pipeline of STEM fields in a more systematic way.”

Can engineering fix itself? If you look closely enough, there’s reason to believe it can.

You could look at NextProf’s partnerships with Georgia Tech and University of California, Berkeley. You could talk with all of the former program participants who choose to return as mentors.

You could also look at the chairs of U-M’s 13 academic departments, six of which are currently held by women.

Or you could keep an eye on that wall in the Lurie Building, photos of everyone who has led the College since it began back in 1855. True, every face is white and male.

That wall will soon welcome another new face, Gallimore’s own – the first African-American dean in the College’s history. Another small sign of what, it is hoped, is a shifting tide.

*NextProf was founded in 2012, and has since expanded to three workshops. NextProf Engineering, founded in 2015, is held every spring and is open to all U-M students and postdocs. NextProf Pathfinder, founded in 2018, is open to first- and second- year PhD students and Master’s students considering a PhD. NextProf Nexus, the original NextProf workshop, began in 2018 when the University of California, Berkeley joined U-M as a partner and sponsoring institution; the Georgia Institute of Technology joined as a partner and sponsoring institution the following year. Now, the three universities jointly and equally put on NextProf Nexus, taking turns hosting it on each of the three campuses.