U-M researchers to help unravel Mercury, solar system mysteries

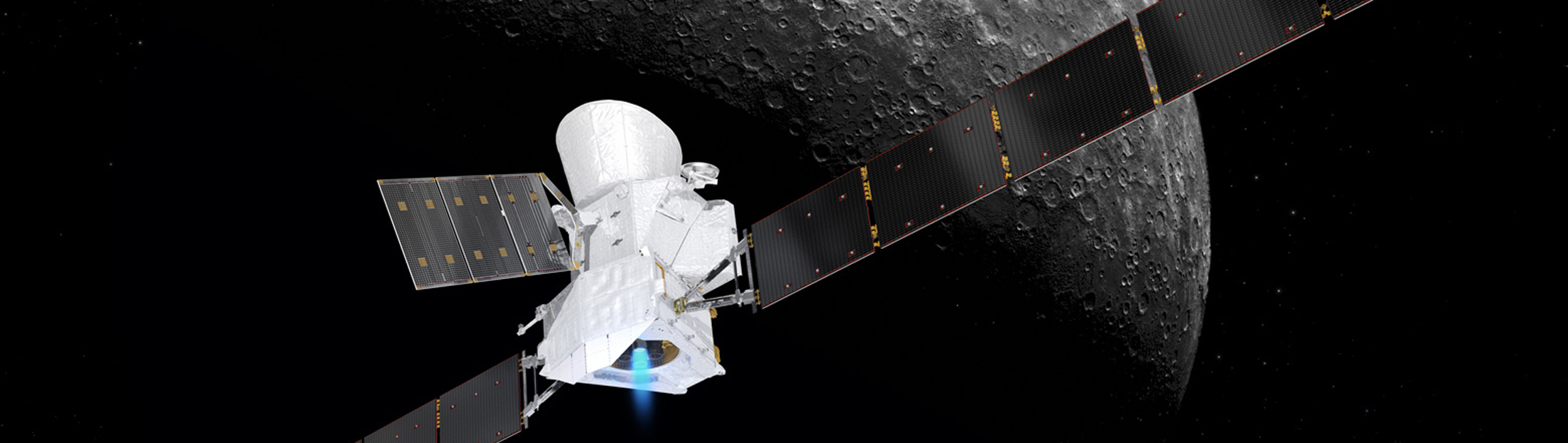

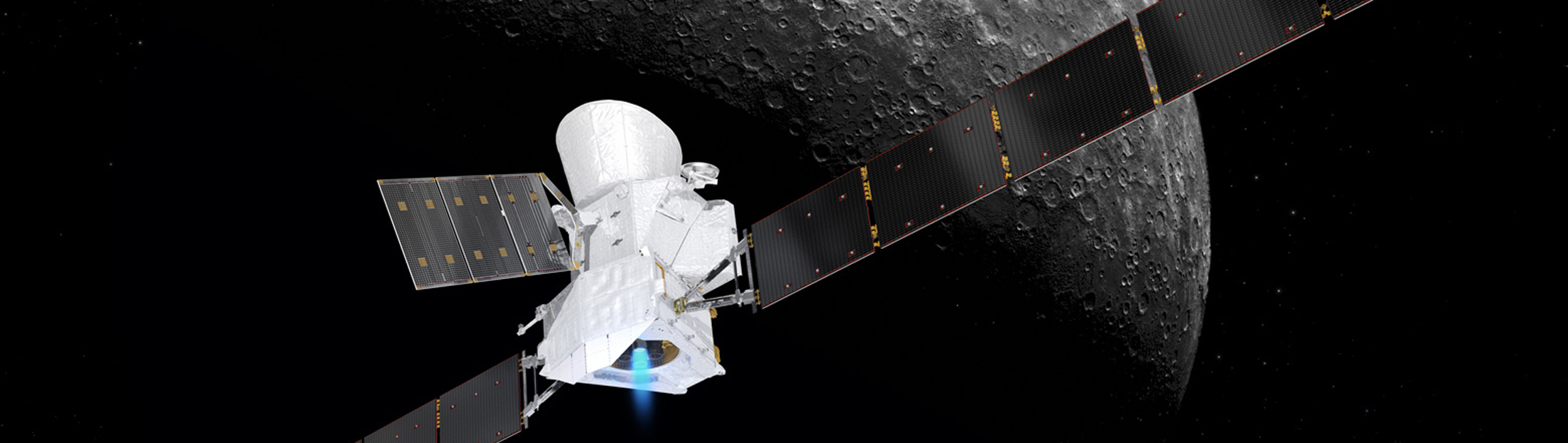

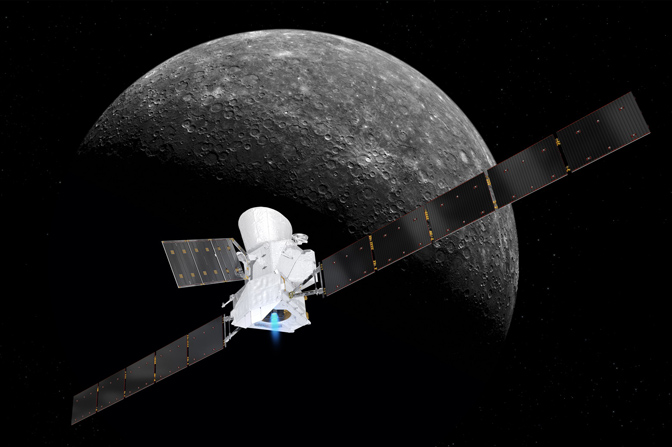

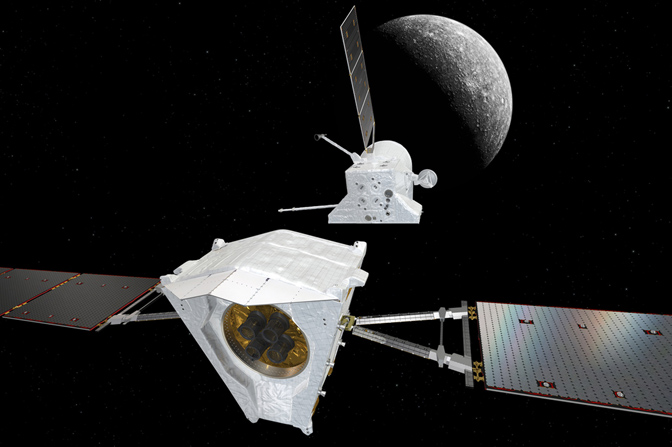

In ESA’s BepiColombo mission, an examination of the particles in Mercury’s upper atmosphere will shed light on what the planet is made of.

In ESA’s BepiColombo mission, an examination of the particles in Mercury’s upper atmosphere will shed light on what the planet is made of.

For only the third time in history, a spacecraft will visit Mercury to shed light not only on the planet’s own long-standing, fundamental mysteries, but on the formation and evolution of the solar system as well.

Two University of Michigan researchers are involved in the European Space Agency’s BepiColombo mission, charged with analyzing the chemical makeup of gases in Mercury’s outermost atmosphere. Stefano Livi, research professor of climate and space sciences and engineering is principal investigator on the spacecraft’s neutral particle spectrometer, which measures the composition of the upper-most atmosphere. James Slavin is a co-investigator on the same instrument. The spacecraft is scheduled to launch from French Guiana on Oct. 20.

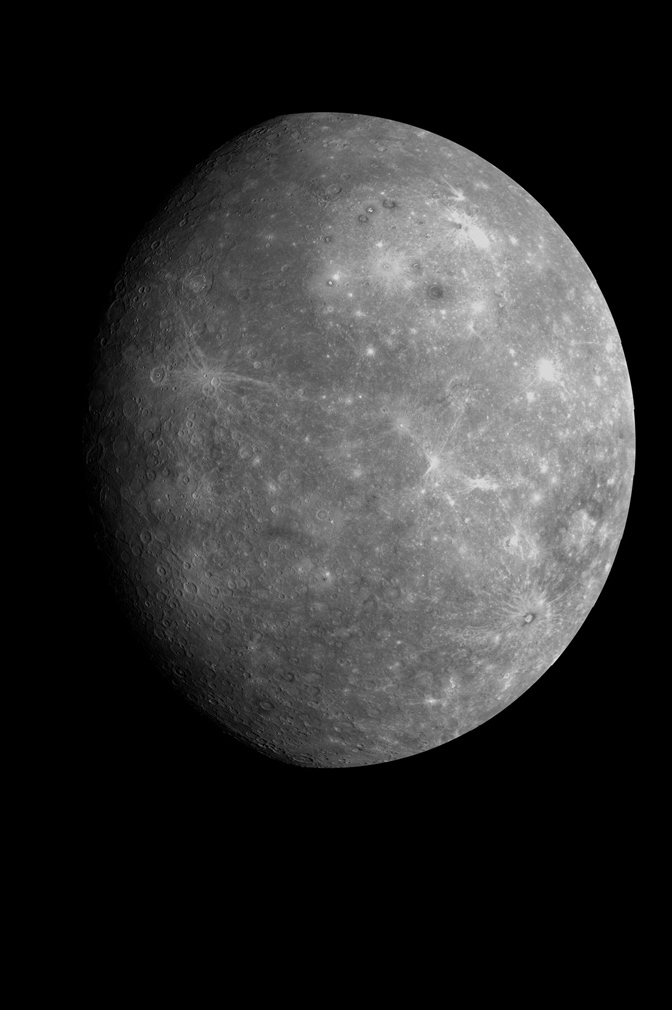

The mission will seek answers that have remained elusive through decades of space exploration that have left Mercury, first visited in the 1970s, the least explored terrestrial planet.

Is the planet’s core liquid or solid? Are the planet’s tectonic plates in motion? Why does Mercury—like Earth—have a magnetic field, while other planets don’t? What is the composition of Mercury’s tenuous atmosphere, and what processes create and destroy it? And are we 100 percent certain that’s water, frozen in the shadowed areas of craters at the poles?

The answers to these and other questions gleaned from BepiColombo should also help explain how the rest of the solar system developed—and what may lie ahead for it.

“As human beings, we all want to know how we came to be as a species on this planet and, eventually, what’s going to happen to us,” Slavin said. “It’s all ultimately about origins and destinies.”

As human beings, we all want to know how we came to be as a species on this planet and, eventually, what’s going to happen to us.

James Slavin, CLaSP professor

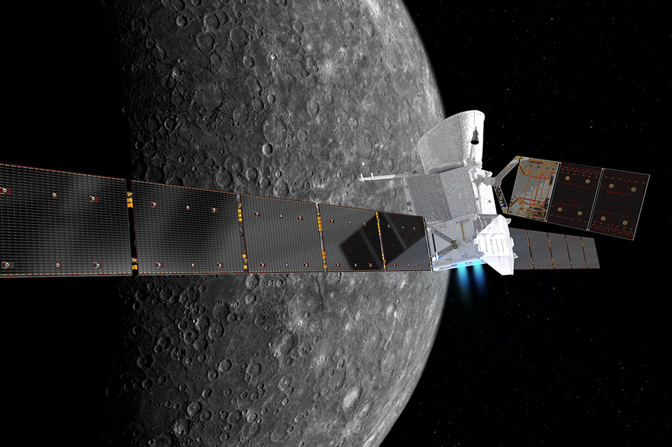

ESA’s first Mercury mission is being conducted in partnership with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency—with both agencies responsible for one of two satellites. ESA will operate the Mercury Planetary Orbiter to hover in close proximity to Mercury, while JAXA will oversee the Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter to study the interaction of Mercury with the solar wind.

Livi and Slavin’s involvement centers on the particle spectrometer, called Strofio, (from the greek work “strofi,” meaning to rotate). The instrument aims to determine the composition of Mercury’s outermost atmosphere.

The technology uses a rotating electric field paired to a time-of-flight system to measure the mass of particles in the upper layers of Mercury’s atmosphere. Gas first passes through Strofio’s extremely efficient ionization region, where neutral gas is ionized. Subsequently, a radio frequency electric field bends the trajectories of the ions so that each particle is essentially time-stamped. The ions are then detected by a 2D detector system.

Researchers can determine a particle’s mass and charge by how long it takes to travel from the electric field to the detector system. And that information will give researchers their best look to date at the makeup of Mercury itself.

“It is ironic that after 44 years of discovery of Mercury’s atmosphere, we still do not know what processes are responsible for continuously refilling this tenuous envelope,” Livi said. “Many theories have been developed, and they all make sense. But without measurements of what this gas is made of, how it reacts to external events, and how it is swept away from the planet, we are working almost completely in the blind.

“And it is not just curiosity: these phenomena have acted on the surface of Mercury and all other bodies in the solar system for billions of years. What we see today is as much the product of these changes as it is a track of the original composition of the planet. ”

Short of landing on the surface and drilling a hole to the core, researchers have four options for gathering information about a planet’s composition. Information can be gleaned from the time it takes a spacecraft to complete its orbit, pictures taken of the surface, analyzing the fluorescence created when X-rays and cosmic rays interact with the surface, and analyzing the atmosphere.

“A planet’s atmosphere comes from the surface—representing a mass transfer of particles to higher altitudes,” Slavin said. “With BepiColombo and Strofio, that’s the one material that we can actually physically touch to understand the planet’s makeup.”

Understanding what particles are in the atmosphere and how they’re impacted by proximity to the Sun will answer questions about Mercury’s magnetic field and how it interacts with the solar wind, a stream of charged particles emanating from the Sun.

Slavin has been connected with every mission to Mercury thus far. NASA’s Mariner 10 was the first spacecraft to fly by Mercury in 1974 and 1975, providing our earliest close-up understanding of Mercury and uncovering the existence of the atmosphere and of the magnetic field. As a graduate student at UCLA, Slavin used Mariner data to examine the the planet’s plasma processes and their interaction with the solar wind.

After lifting off from Cape Canaveral in August 2004, NASA’s MESSENGER travelled more than six years before its first rendezvous with Mercury. Slavin served as co-investigator for the mission’s magnetometer investigation.