Europa’s ocean: New evidence from an old mission

An image from Hubble and data from Galileo support the theory that this moon is home to global body of water.

An image from Hubble and data from Galileo support the theory that this moon is home to global body of water.

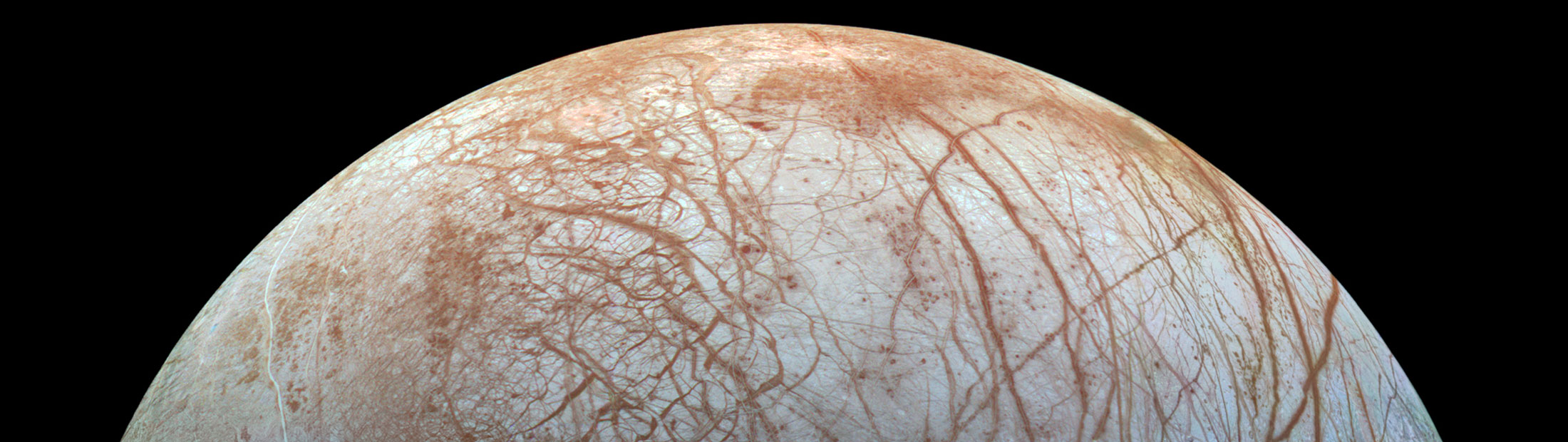

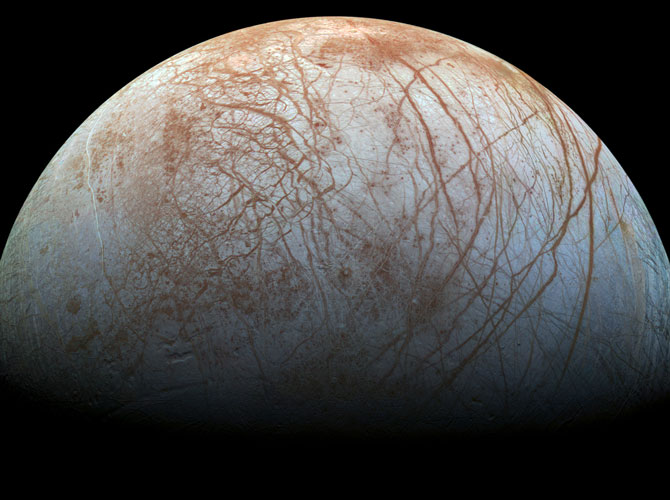

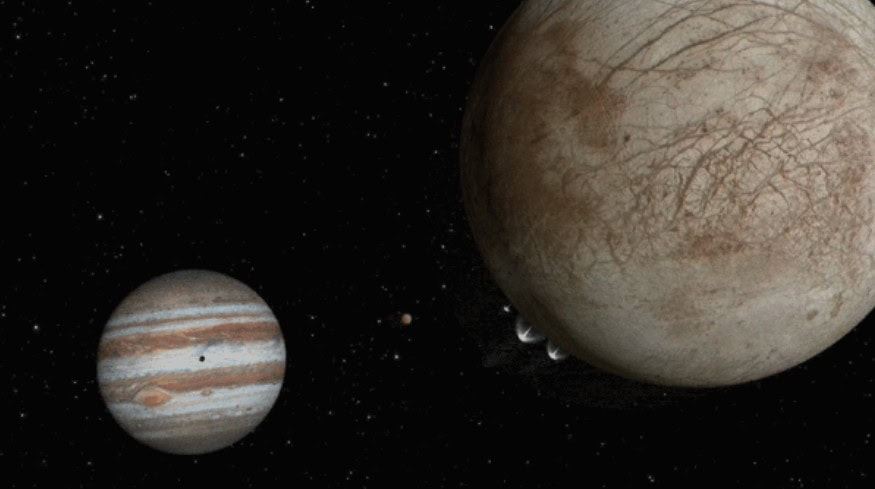

Europa, a moon of Jupiter, has long been suspected of hiding a global ocean beneath its icy surface, and University of Michigan researchers have now found the strongest evidence yet to suggest it has plumes ejecting water from its subsurface into space.

The researchers conducted a new analysis of old data—information captured by NASA’s Galileo mission in the late 1990s. Paired with images of Europa captured by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, the findings provide a boost to the idea liquid water is present in the shallow subsurface and that it occasionally bursts through the moon’s ice layer into space as plumes. A paper on the research is published today in Nature Astronomy.

Led by Xianzhe Jia, associate professor in the U-M Department of Climate and Space Sciences and Engineering, the researchers reexamined readings captured by Galileo as it flew through an area later seen to have suspected plume activity. They found that the probe measured a rotation of the magnetic field and plasma activity consistent with a plume similar to those seen by Hubble.

The numbers appeared abruptly during a roughly three-minute stretch of a single low-altitude pass. And then they disappeared just as quickly – as if Galileo had passed through something ejected from the surface.

“In that three minutes, we saw the magnetic field change strength by an order of about 200 nanoteslas,” Jia said. “It was a very big, very peculiar change.”

A nanotesla is a measure of the strength of a magnetic field.

In 2012, Hubble captured ultraviolet data of Europa showing what many scientists consider strong evidence of a water plume ejected from beneath the moon’s surface. But the grainy quality of the image is far from definitive and there have previously been little direct data to confirm what it shows.

“Hubble’s was a remote detection,” Jia said. “You see from far away this anomalous feature on the disc of an image, and you’re trying to persuade people it was a plume.”

This one (Galileo) flyby was the closest one of the mission and just happened to be in the right region.

Xianzhe Jia, associate professor in the U-M Department of Climate and Space Sciences and Engineering

Additional images of suspected plumes were captured in 2014 and 2016 but provided no greater degree of certainty. Evidence from the source is needed to support the claim—something that’s difficult to come by when the research subject is 390 million miles away.

But in 2017, Jia and Margaret Kivelson, a U-M research professor who also holds an appointment at UCLA, realized that evidence may already exist in the form of data collected by Galileo years earlier. Kivelson had been the principal investigator for the magnetometer on that mission, which included 11 flybys of Europa during its extended trip to Jupiter.

REUTERS

MAY 15, 2018

Europa’s plumes make Jupiter moon a prime candidate for life

NEW SCIENTIST

MAY 14, 2018

Probe saw plumes on Europa 20 years ago – we just didn’t notice

DAILY MAIL

MAY 14, 2018

POPULAR MECHANICS

MAY 14, 2018

NASA Spacecraft Likely Flew Though a Europa Water Plume in 1997

MASHABLE

MAY 14, 2018

A new study just inched us closer to understanding if Jupiter’s moon Europa could host alien life

CNET

MAY 14, 2018

NEWSWEEK

MAY 14, 2018

Potentially habitable Europa has plumes that could reshape hunt for alien life

Their hunch was that if the Hubble images did indeed show plumes, Galileo may have passed near one of them. And the hunch proved to be correct.

“I do feel we were lucky—maybe fortuitous is a better word,” Jia said. “The pass not only had to be close to the surface, but it had to be in the right region in order to see a plume like this. This one flyby was the closest one of the mission and just happened to be in the right region.”

William Kurth, a University of Iowa physicist and co-author on the study, helped re-examined data gathered from the Galileo mission.

“We’ve taken a new look at old data that gave us a surprise about Europa,” Kurth said. “The simulations allow us to use the Galileo plasma wave and magnetic field observations to conclude that there was, indeed, a plume on Europa during Galileo’s Europa 12 flyby.”

When NASA’s Europa Clipper mission launches, possibly as early as 2022, Jia and Kivelson will team with James Slavin, chair of U-M’s Department of Climate and Space Sciences, and Justin Kasper, associate professor in the Climate and Space department, as co-investigators. That project will provide another opportunity to gain a better understanding of the moon.

“The discovery of the signatures of a plume at Europa in magnetic field and plasma wave data acquired more than 20 years earlier reflects the long horizons required in the study of planetary environments,” Kivelson said. “Looking into the future, we are pleased that the new interpretation of Galileo data will influence plans for the Europa Clipper.”

The paper is titled, Evidence of a plume on Europa from Galileo magnetic and plasma wave signatures (http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41550-018-0450-z) . The research was funded by NASA.