Ed Lesher: Aircraft Hall of Famer

This aeronautics professor taught students in mid-air and flew into record books.

This aeronautics professor taught students in mid-air and flew into record books.

Edgar J. Lesher stayed with his sister in Florida for five straight summers, waiting for the perfect day. He was looking for a clear path of good weather from St. Augustine, Florida, all the way to Tucson, Arizona.

The first three summers, Lesher was too anxious to sleep, forfeiting a number of opportunities. He reached out to Jack Lousma (BSE Aero ‘59), who told him astronauts often took medication. The next two summers, Lesher got enough sleep, but the weather didn’t hold.

Finally, at 3:00 AM on July 2, 1975, Lesher rose from his bed and headed to the airport for what would become his seventh and final world record-breaking flight in the Teal, an airplane he built himself.

Lesher, who would tell you to call him “Ed” once he got to know you, was different things to different people. He was a husband to Margaret and a father to ten children, including four sets of twins, though one child passed away at birth.

Lesher also was a professor of aeronautical engineering at the University of Michigan. After earning a bachelor’s degree in mathematics at Ohio State University in 1938 and a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering at Michigan in 1940, Lesher left Ann Arbor to work at the Douglas Aircraft Company in California. About a year later, he went on to Texas A&M College, where he helped with the Civilian Pilot Training Program and earned a pilot’s license. In 1942, he returned to Michigan as a professor.

And within this personal and academic mix was his acclaim as an aircraft homebuilder. A member of the Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA), Lesher built two impressive planes, and had plans for a third. The first was the Nomad, a two place, aluminum, semi-monocoque recreational craft. The second was the Teal, a sleeker, single place version of the Nomad, designed specifically to break world records. And both were pushers, which meant the propeller was in the back.

University Life

Before Lesher started building his own aircraft, he taught aeronautics at Michigan, and would continue to do so until his retirement in 1985.

Most students who closely interacted with Professor Lesher came away much more inspired than those who only knew him as a lecturer. In large classes Lesher would face the blackboard and fill it with equations, explaining everything as he went but never facing the class.

“I think I learned more from Professor Lesher in casual conversations in the hallway than I learned from any of my other professors in full courses,” said Barnaby Wainfan (MSE Aero ‘78).

“He wasn’t a passionate and inspiring lecturer, by any means. But he had an almost infinite willingness to share information and help you learn. And once he decided you were somebody who cared about it, he was always available, always interested in talking,” said Wainfan.

Lesher taught one popular class, in flight dynamics, where he would pilot a Cessna and take three students with him in the air. Students would record measurements and perform tests to determine the plane’s performance, stability and control.

You could tell he liked the hands-on part of his job,” said Thomas Galloway (BSE Aero ‘62). “It was kind of like he was one of the group, you know? He didn’t act like he was any better than the students.”

“He just loved airplanes, it was very clear,” said Wainfan.

The Nomad

Early in his professorship, Lesher took another short leave to work for the Stinson Aircraft Company, a division of Convair, in nearby Wayne County. One project that he spent quite a bit of time on was a four place light aircraft, the Convair Model 106 Skycoach. It was a pusher, which continued to intrigue Lesher, even after the project was abandoned and he had returned to Michigan.

It took more than ten years for him to revisit the idea, but in August 1958, Lesher attended one of the early EAA fly-ins in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where like-minded aircraft enthusiasts came together to show off their homebuilt planes. Lesher returned to Ann Arbor inspired to build his own. And it would be a pusher.

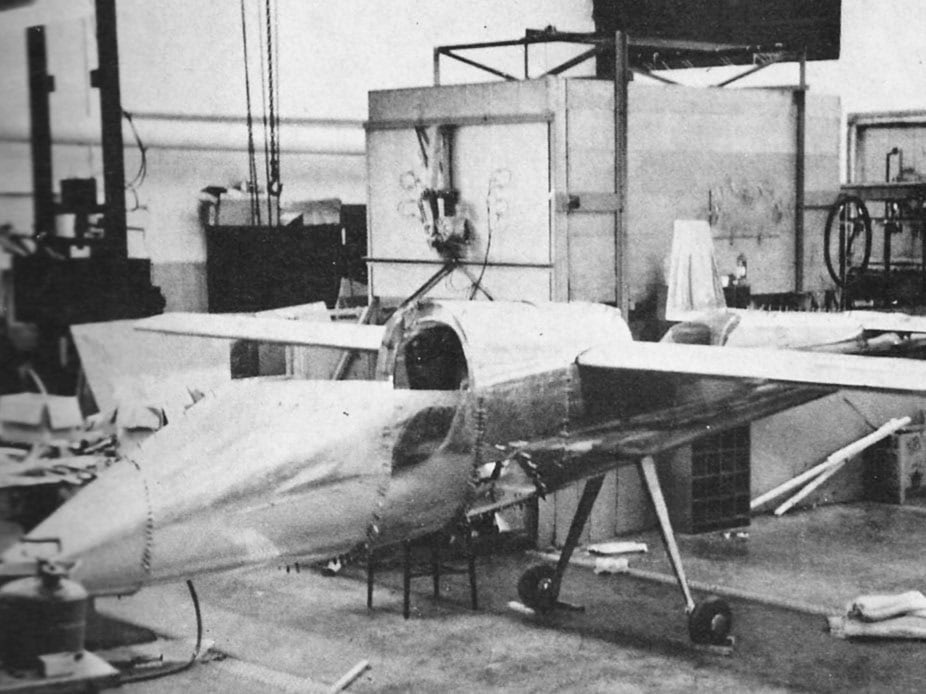

Construction of the Nomad began in February 1959. Lesher called it a personal project, as it was separate from his responsibilities as a professor. But that didn’t seem to prevent him from building it on campus. And students noticed.

“Early on, I found out about the Nomad, which he was already building in the basement of the East Engineering building,” said Malcolm Monroe, an undergraduate aeronautics student at the time. “I was able to finagle some shop privileges there.”

“They were very protective of the plane, and did not want students around it, but I did manage to touch it a few times, and help just a bit with the construction,” said Monroe.

“We felt it was pretty unique,” said Galloway. “It was nice being able to see what was possible when you had a passion for certain things.”

Lesher embraced the interest of his students, and assigned problems in his courses that helped to produce data points to better predict the performance of the Nomad.

Beyond giving his students real-world practice problems, Lesher also exposed them to one of the more significant design challenges of building a pusher.

“A major concern of his was vibration in the drive shaft of the propeller,” said Galloway.

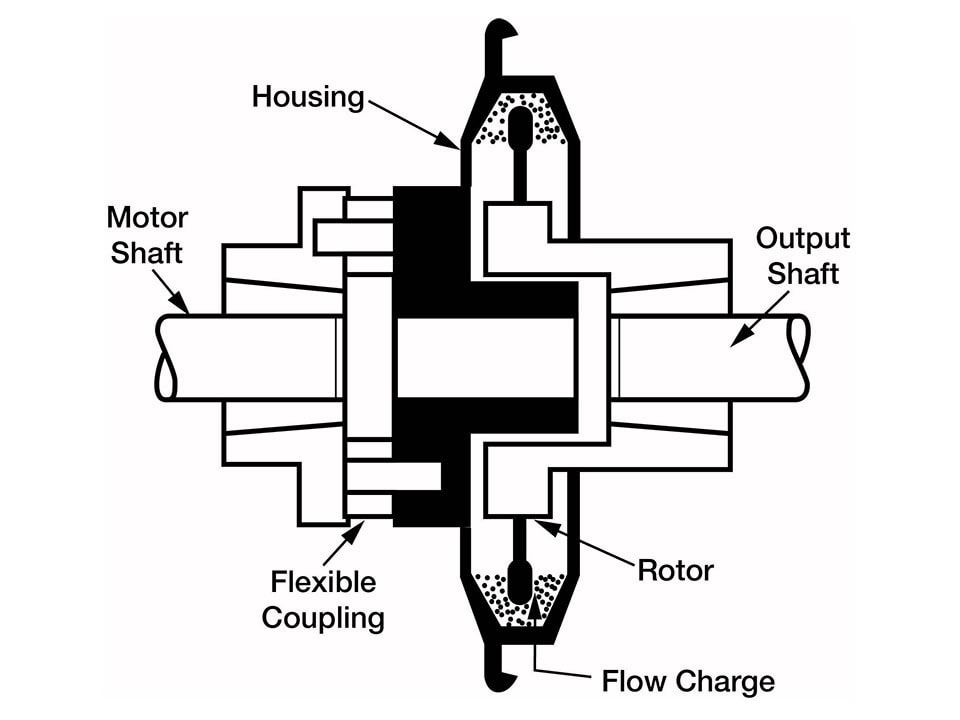

The engine in the Nomad, a 100 horsepower 0-200A Continental, sat right at the center of the plane, behind the cockpit. The propeller, however, was more than eight feet away, at the rear of the aircraft. An extension shaft was needed to connect the two, but a shaft that long would create a lot of vibration due to the starting torque.

“So Ed contacted Molt Taylor,” said Robert F. Pauley, a fellow EAA member who documented much of Lesher’s work. “He designed the Aerocar, which was a so-called ‘roadable’ airplane. And he used an extension shaft in that.”

After conferring with Taylor and a few other colleagues, Lesher went with the Dodge Flexidyne 9C dry fluid coupling, which he installed between the engine and the shaft. The coupling would ease the acceleration of the extension shaft and reduce the starting torque.

Once construction was complete, Lesher moved everything to Willow Run Airport in nearby Ypsilanti to do the final assembly and prepare for flight. And in October 1961, after 5,000 hours of construction, the Nomad flew.

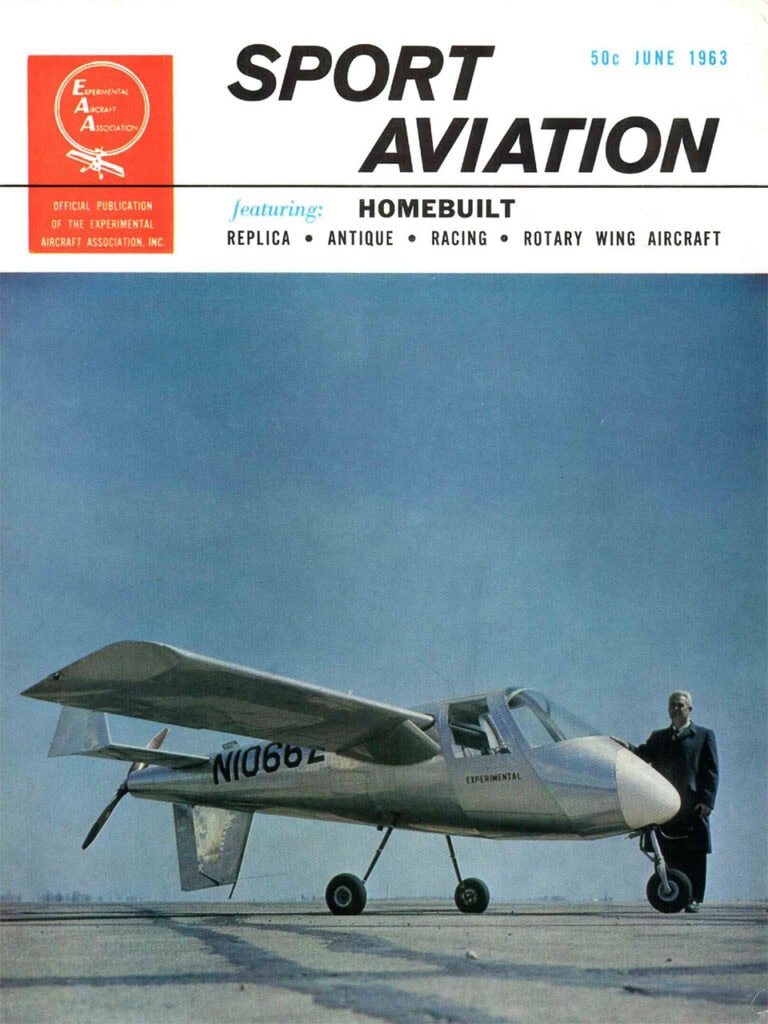

“This was a refreshing experience,” wrote Pauley in EAA’s Sport Aviation Magazine in June 1963, after getting a chance to fly in the Nomad with Lesher.

“The low-set instrument panel, below knee level, allows an excellent view forward and down, rivaling the view from a helicopter. Having once become accustomed to the ‘Nomad’s’ most outstanding feature, one can sit back and relax in the roomy cabin, enjoy the view and appreciate the plane’s other virtues.”

In 1962, Lesher flew the Nomad to the EAA fly-in, which had moved to Rockford, IL.

“By weeks end, the grass around Nomad had been worn by the shoes of thousands who had inspected the ‘funny looking little plane,’” wrote Ann Pellegreno in the Summer 1970 issue of Air Trails: Homebuilt Aircraft.

Also at the fly-in was Lesher’s friend, Leeon Davis, a fellow homebuilder who had brought his DA-1 airplane to the event back in 1958.

While the two were talking, Davis revealed to Lesher that he was thinking about going for distance records with his next airplane, the DA-2. Specifically, he was interested in records for the 500 kilogram class of aircraft as classified by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI), the international organization that certifies world aviation records.

Lesher needed a new project, so he stole the idea.

The Teal

Immediately upon returning home, Lesher wrote to the National Aeronautic Association, which represents the FAI in the U.S., asking for more information. After learning about the number of available records for a plane in the 500 kilogram class, Lesher’s ambition became designing one that would set as many records as possible. He would call it the Teal.

Lesher had his work ahead of him, as there were a number of trade-offs to consider when designing a world record-breaking aircraft. He first figured that a 50 horsepower engine would be ideal for the Teal, but he couldn’t find one with the right specifications. Instead, he decided on 100 horsepower, and later opted to pull his Continental out of the Nomad.

The next decision was whether to go with the pusher concept again. Lesher calculated that the extension shaft and Flexidyne coupling would add an extra 50 pounds compared to a tractor design (in which the propeller is at the front). Despite the weight penalty, Lesher committed to building another pusher, expecting it to “make a good showing.”

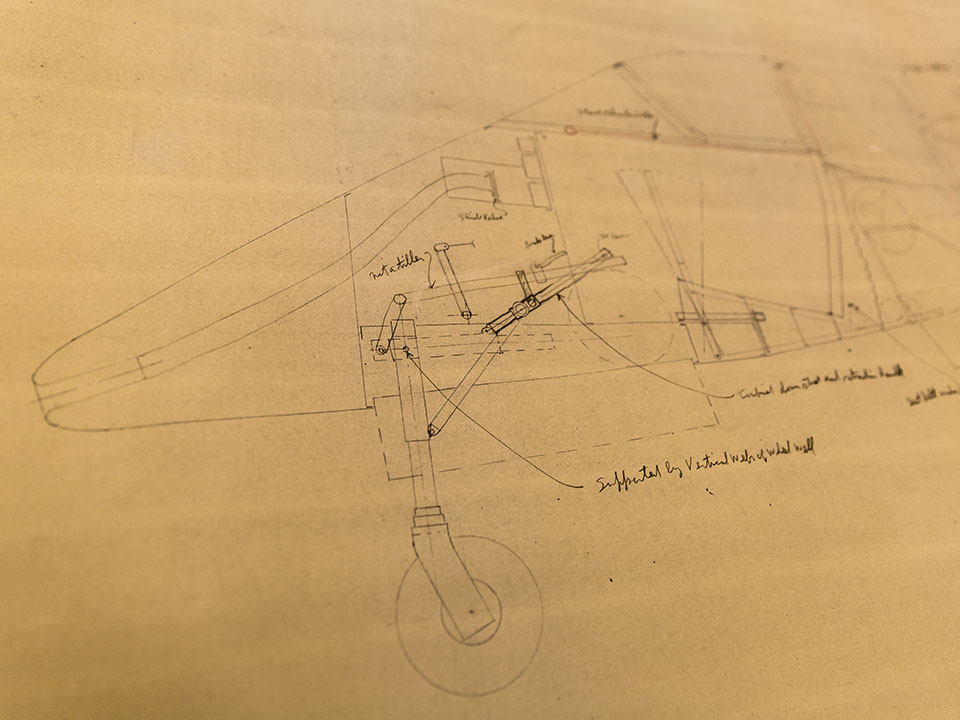

Most of the difficult design decisions for the Teal were related to weight and aerodynamics. Lesher knew that, unlike the Nomad, he would have to implement a retractable landing gear to greatly lower the drag. But that would add weight. So he designed the simplest landing gear he could devise, which would require eighteen separate operations and take about two minutes to fully retract.

Lesher also seriously considered not adding brakes to the Teal, just to save weight. Other record-breaking planes did this, but after researching runway lengths and calculating the required stopping distance, he drew in a small brake for the nose wheel.

The final design decision Lesher made concerned not the Teal’s form but his own — which he described in the March 1968 edition of Sport Aviation:

“My first idea was to use a jockey pilot, as my weight was well over 200 lbs. But this would forfeit the best part. I decided that this was the perfect incentive to lose weight, and this is a continuing feature of the project.”

Just two months after his conversation with Davis in Rockford, Lesher had completed the preliminary design and was ready to begin building the Teal. And like the Nomad, Lesher built it on campus, with students helping with performance calculations and some of the assembly.

On April 28, 1965, construction was complete and the Teal was ready for flight. Lesher took off from Willow Run Airport and made two laps, which lasted about ten minutes.

“The airplane behaved exactly as expected,” wrote Lesher.

The First Go

Over the next two years, Lesher would build up flight time in the Teal. For his first 50 miles, he stayed within a 25 mile radius of Willow Run Airport, which was a requirement set by the Federal Aviation Act of 1958 for homebuilt aircraft. It took him about three months.

Once the Teal was certified, Lesher was ready to do some real flying. He entered the 1965 AC Flight Rally, a competition that kicks off the annual EAA fly-in. Pilots would bring their planes to various starting locations a few hundred miles from Rockford and “fly-in” to start the convention.

The rally featured a wide range of aircraft types and was judged with a handicap system based on piloting skill and aircraft capabilities. Lesher had won first prize the previous year with the Nomad, but this time bad weather forced him to abandon the rally, and he arrived in Rockford later than planned.

Lesher entered the Teal again the next year and was awarded fourth place. But overall, the plane still performed better than he expected.

By 1967, Lesher was happy with how the Teal was flying, and was ready to start his record attempts. The first three he would tackle were all for maximum speed in a closed course, at lengths of 500, 1,000, and 2,000 kilometers. This meant he could define a course, and just do multiple laps to meet the distance requirement.

All three records had been last set between 1952 and 1954 in Europe. In fact, one of Lesher’s other motivations for attempting to break the records was because none of them were held by Americans.

Lesher settled on a course between Willow Run Airport and the WMUS radio tower in Muskegon. Specifically, the starting point was the chimney of a nearby house owned by Lee Koepke, a local airplane mechanic. The route measured 250.14 kilometers, which worked out well for the distances Lesher needed to fly.

Lesher made his first attempt on May 22, 1967, flying to Muskegon and back with an average speed of 292.17 kilometers per hour. FAI certified the flight and gave Lesher the 500 kilometer record over Iginio Guagnellini’s 249.08 kilometers per hour. One down.

One month later, on June 30, 1967, Lesher attempted two laps of the course to challenge the 1,000 kilometer record held by Nello Valzania, whose average speed was 240.52 kilometers per hour. Lesher completed the flight at an FAI certified average speed of 272.32 kilometers per hour, successfully earning the record. Two down.

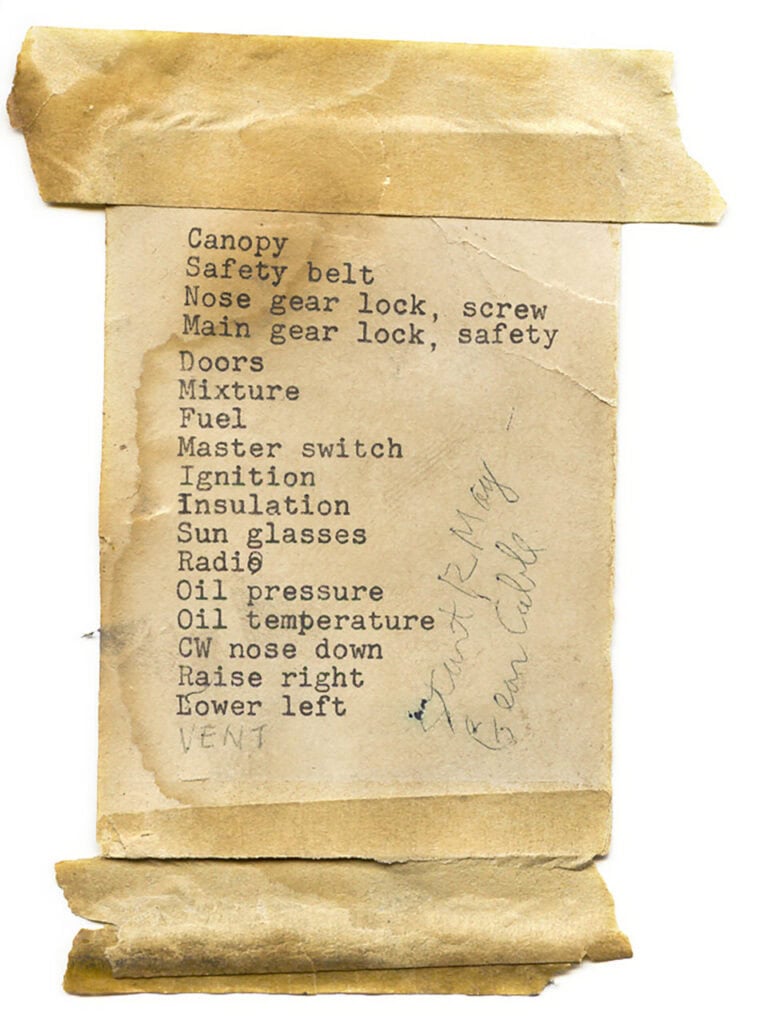

And then on October 20, 1967, Lesher flew four laps of the course at an average speed of 228.26 kilometers per hour, beating the previous 2,000 kilometer closed course speed record of 183.43, held by Albert Rebillon. And in a matter of months, Lesher held three world records.ENLARGEIMAGE: Ed Lesher’s startup checklist from the cockpit of the Teal. Photo University of Michigan.

A Significant Delay

Lesher wrote in March 1968 that he planned to go for three more FAI records in July of that year. The records were for altitude, distance in a closed course and distance in a straight line. But a setback would delay his attempts more than two years.

On the afternoon of May 6, 1968, as Lesher was flying the Teal over Ann Arbor, his engine cut out. At the time, while in mid-air with no power, he thought that the drive shaft or part of the engine had failed, and worried that trying to restart it might cause the tail assembly to separate.

So with no thrust to rely on, Lesher pointed the Teal towards the Ann Arbor Municipal Airport, which would have been closer than Willow Run. And it looked like he was going to coast in for a gentle, unpowered landing.

But as Lesher began the laborious process of lowering the Teal’s landing gear, the sudden drag caused the nose to dip down, taking the plane and Lesher with it. Now short of the runway, the Teal crashed, and hit a tree just across State Street from the airport.

Lesher was able to walk away from the accident mostly unhurt, save for a large bruise on his left bicep. But the damage to the Teal was significant.

Lesher later determined he had run out of fuel. After 2,505 hours of total flight time and 178 hours in the Teal, this simple but serious mistake would set him back years. But Lesher was also lucky. Unlike others in the homebuilt community, he had managed to get his plane on the ground without more serious injury.

The Teal, Rebuilt

After a year of rebuilding the Teal and another spent logging flight time, Lesher was ready to get back to his records.

The first record he went after was for maximum distance in a closed course, and Lesher opted to use his familiar route of Willow Run to Muskegon.

On September 9, 1970, at 6:06 AM, Lesher took off in the Teal from runway 27L, passed over Koepke’s chimney, and turned to head for Muskegon.

Five laps and 12 hours later, Lesher passed over the chimney one last time and turned in for a landing. Many of his friends were waiting, along with a photographer from Detroit’s Channel 7 news.

Official measurements were made, and the remaining fuel was siphoned from the tank. Seven of the original 42 gallons remained – not nearly enough to attempt a sixth lap. But it didn’t matter. A couple of months later, FAI certified that Lesher had earned his fourth world record with a distance of 2,501.4 kilometers, again beating a record held by Albert Rebillon of France.

Three more years would pass until Lesher’s next set of records were attempted, this time for a couple of sprints. In September 1973, Lesher flew to Connecticut to attempt one record for speed over a course between 15 and 25 kilometers, and a second for speed over a three kilometer course.

After malfunctions with the timing equipment and delays due to local air traffic, the Teal easily conquered both records. Lesher flew an average speed of 272.195 kilometers per hour in the 15/25 kilometer course, earning the first record for the Teal’s class, and 278.58 kilometers per hour in the three kilometer course, beating a five year old record set by Donald Sinclair. And Lesher only had to push the Teal to 70 percent of its rated power to do it.

Walter Carr, who had officiated Lesher’s first three record flights back in 1967, later asked Lesher why he didn’t “firewall” the Teal to go faster. Lesher, with a bit of humor, described his response to Carr in the June 1974 edition of Sport Aviation:

“Aside from the fact that the firewall is behind me in the Teal, I felt it was better to fly conservatively and finish rather than push and have something go wrong.”

After certification by the FAI, Lesher now held six world records.

The Final Record

Lesher got to the St. Augustine airport at 4:30 AM on July 2, 1975, for his final record attempt: distance in a straight line. There he met his “4 O’Clock Club,” comprised of friends and officials.

They pushed the Teal up onto three certified scales, and Lesher threw in everything that would be going on the long flight: some water and hard candy, charts, two barographs that helped certify the flight and finally his AC Rally hat. Lesher then climbed in, and after the total weight came in a few pounds shy of the 500 kilogram limit for his record class, he decided to add a little bit more fuel.

After sealing the fuel tanks and the barographs, Lesher and his team took the Teal out to the runway. At 7:16 AM, the final record attempt began.

Most of the flight was uneventful. There was some haze around Jackson, Mississippi, and some dark clouds with light rain in Abilene, Texas. But the real drama waited until just outside Tucson.

“I asked myself ‘What am I doing here? Should I make a 180?’ I had been flying for more than 12 hours and was within 60 miles of breaking the record,” wrote Lesher in the February 1976 edition of Sport Aviation.

He was approaching a pass between Mount Lemmon and Mica Mountain, which borders Tucson to the east, when he spotted a wall of approaching thunderstorms. Lesher had to decide whether to turn around and lose the record, turn north toward a closer airport and be short of the record or push through and hope for the best.

Lesher decided to push on, and as he approached the pass, he could finally see the Tucson basin through the clouds, though just barely. Now reassured, he powered through the rain, made it past the mountains and the storm, flew over his record line and landed at the Phoenix-Litchfield Airport.

Lesher was in the air for 13 hours and 27 minutes, flew a total of 2,953.89 kilometers and broke the record set 18 years earlier by Kaarlo Henrik Juhani Heinonen of Finland.

Lesher had set his seventh and final world aviation record.

Lesher’s Legacy

Lesher’s accomplishments in aviation were well-noticed and recognized.

The FAI awarded him the Bleriot medal four times for his record-breaking endeavors, and Lesher was inducted into the Michigan Aviation Hall of Fame in 1988 and the EAA Hall of Fame in 2006.

But perhaps most significant was the legacy he left with the students he inspired. Many were successful in the aeronautics industry, which may not be rare for a Michigan Engineering graduate, but Lesher’s students felt he had significantly influenced them.

Malcolm Monroe had a long career in anti-missile research in Cape Canaveral. Thomas Galloway spent 35 years at NASA’s Ames Research Center, working on developing software to evaluate new aircraft designs. Bruce Carmichael, one of Lesher’s early students, was a pioneer in the world of laminar flow and super low-drag aerodynamics. And Barnaby Wainfan, a technical fellow at Northrop Grumman, has worked on more than 21 different aircraft, including being the lead aero designer of the X-47B.

“I think he’s probably the single most important teacher I’ve had in my entire career,” said Wainfan. “He was the reason I came to Michigan.

“I originally saw a picture of the Teal in the September 1967 issue of Flying Magazine. Just one little picture. I was 11 years old at the time and I just thought it was the coolest thing I’d ever seen.

“And when the time came for me to choose where I was going to go to graduate school, I basically had a choice between Stanford and Michigan. Everything else said Stanford, but I came to Michigan because of Professor Lesher, and never regretted that decision.”