Designing for our own

CSE students designed technology for a fellow student who returned after a decade away because of a brain hemorrhage.

CSE students designed technology for a fellow student who returned after a decade away because of a brain hemorrhage.

In the winter of 2016, David Chesney was approached with a unique challenge: help a current University of Michigan undergraduate student who is severely disabled adapt to his environment and learn as his classmates do.

Chesney, a lecturer in electrical engineering and computer science, has been teaching EECS 481 (listed as EECS 498 in fall 2017) for nearly a decade. The course is funded by a grant from the Mott Golf Classic and challenges students to utilize rapidly developing technology like motion sensors and augmented reality headsets donated by the Microsoft Corporation to help “clients” with unique physical and cognitive challenges.

“It’s a very unique relationship,” Chesney said. “Software developers want to build the thing they can sell to a million or 10 million people, but working with a single person with very unique user needs, it flips the students upside down a bit.”

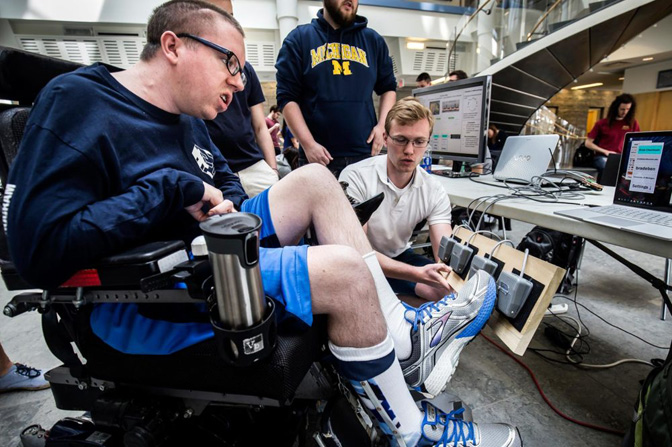

The challenge for students in the fall of 2016 came in the form of Brad Ebenhoeh, a now 30-year-old sophomore in aerospace engineering. Growing up, Ebenhoeh wanted to become an astronaut, but at age 19, he suffered a brain hemorrhage that paralyzed the right side of his body, limited his vision, confined him to a wheelchair and forced him to leave the University for a decade. After rehabilitation, Ebenhoeh successfully re-enrolled and returned to campus. His cognitive abilities recovered, but he is still confined to his wheelchair and is assisted by a caretaker, having only regained part of the vision in his left eye and a bit of the functionality of his left hand and foot.

CSE Lecturer David Chesney’s students designed technology to help a student return after a decade away because of a brain hemorrhage.

“Some of the guys in the class were fascinated to be working with me because I have more severe disabilities than your average disabled person has,” Ebenhoeh said.

Chesney’s students instead capitalized on the abilities Ebenhoeh had and built software and hardware based on his needs as a student. Screens with large, bolded text compensated for his limited vision and allowed him to read lecture slides and notes. Despite his diminished dexterity, a piano keyboard system let him adjust the tempo, pitch, and tone of notes in order to once again play the piano. Pedals for his left foot switched between alphabetical and numerical keyboards, giving Ebenhoeh the ability to take notes and send emails more easily than just using his left hand.

“[The students] determined that I might have some luck typing with my foot,” Ebenhoeh said. “It was a struggle initially, but it actually worked in the end. I was elated to be typing with two appendages again.”

Chesney loves to see the technology that his students design, but admits there is no technological ‘silver bullet’ that will immediately make Ebenhoeh’s life as it once was.

“I don’t know if my students will ever create the thing,” Chesney said. “It’s more about being a positive life force, and maybe it will lead to something good at some point.“

As the semester ends and the students start new courses, some projects will continue outside of the class, with students dedicating their personal time and working as interns to help implement these technologies into Ebenhoeh’s daily life. But Ebenhoeh, after gaining these adaptive technologies, seems almost as thankful for the sense of connection and partnership he has with the other students.

“We folks in software engineering, we think we’re giving something to the client,” Chesney said. “But the reality is 90 percent of the flow of knowledge and compassion is going from the client back to the students, not the other way around.”