Courage to Resist

In the escalating struggle between the individual and the state, technology favors the powerful. That’s why this Michigan computer scientist and his team of researchers revel in righting the balance.

In the escalating struggle between the individual and the state, technology favors the powerful. That’s why this Michigan computer scientist and his team of researchers revel in righting the balance.

Broadly speaking, Michigan electrical engineering and computer science professor J. Alex Halderman’s work focuses on computer security and privacy, with an emphasis on problems that impact society and public policy. But the Michigan Engineering PhD students he advises make a bolder claim: They want to make the world a better place.

“We all have our own ideas about what that means,” says Matt Bernhard, who works most closely with Halderman on voting security issues. But he agrees with fellow student Benjamin VanderSloot — a member of a group that worked on the award-winning “Logjam” paper that exposed the National Security Agency’s cryptographic practices — who says Halderman’s mission is to “try to do good in as big a way as possible.”

“And that draws in students who feel the same way,” VanderSloot says.

For his part Halderman says he looks for students “who really want to have an impact, and are passionate about the problems they are going to solve.” And his most important role as mentor is to “convince them their workcan actuallymake a difference.”

Halderman’s been trying to make a difference as director of the Center for Computer Security and Society, whose mission is to foster deeper and more frequent interactions among Michigan faculty — not only within his department and at the College but across the entire University — who are tackling the “grandest problems in security,” where technology converges with social science, politics, public policy and law.Enlarge

“We’re certainly a leading place to do security work now,” Halderman says, extending his lean frame along the length of the couch in his office. The place is packed with artifacts emblematic of security — or, more to the point, a false sense of it (a reproduction of an ICBM launch key; a device designed to steal electronic votes; a photo of a security official with a finger in his nose).

“We have momentum, and the room to grow. I want to be the national — even international — leaders.”

But it’s Michigan’s “spirit of wanting to address global problems, and wanting to do that in a practical way,” that moves him most.

“We’re going to be leaders not by playing the academic game but by doing the work that matters,” he says.

“Not just academic armchair solutions. We want to get out in the world and see how things work — and use that understanding to improve things. Close the loop.”

Halderman’s real-world security contributions began while he was a PhD student at Princeton. In the early 2000s, Halderman was part of a group working to expose security flaws in new electronic voting machines. These had been too quickly purchased and too haphazardly installed after the 2000 “hanging chad” U.S. presidential election recount prompted Congress to appropriate more than $3 billion to “modernize” the U.S. election system. Machine manufacturers strenuously resisted research probes and critics’ warnings, and computer science and engineering departments around the country clamored to examine them.

In early 2006, an anonymous insider offered Halderman’s faculty advisor Edward Felten the opportunity to inspect a Diebold-manufactured machine, and Halderman was dispatched to retrieve it. This required a drive to New York City for a meeting in a dark alley with a man in a trench coat, who slipped Halderman a black canvas bag — which Halderman (as if he were in a B-movie) immediately transported to an undisclosed location.

In fairly short order, Halderman and his team would demonstrate that the voting machine inside the bag was no more secure than a typical home computer. They readily hacked it and infected it with malicious code that stole enough votes to change the intended outcome of a simulated election. The resulting paper convinced election officials in several jurisdictions that the machines simply weren’t trustworthy enough to be useful.

Asked now why he was the one sent to retrieve the machine, Halderman laughs. “I don’t know…. I had a car?”

But he also was willing — and learning at that time to “overcome that mental block; that little taboo to even think about breaking a rule. It’s not something decent people do.” (This is to be very clearly distinguished from his research group’s strict “commit no crimes” policy, which is assiduously followed.)

Effective security work requires following one’s curiosity and understanding that, “it’s not your job to make everyone happy. Some people are going to be unhappy that you’re even asking the questions.”

Not long after Halderman arrived at Michigan, he and his students had asked enough questions to be embroiled in his most public election hack yet. In the fall of 2010, Washington, D.C., officials had invited the public to participate in mock voting to test its upcoming internet-based election — the nation’s first. As Halderman has since joked, “It’s not every day you can hack an election without going to jail.”

In less than 48 hours, Halderman and his students had hacked the system and stolen votes. Election officials learned they’d been had only after hearing “Hail to the Victors” when the voting page was displayed. And the D.C. online voting plan was summarily scrapped.

That same year, an Indian security researcher, essentially acting as an unprotected whistleblower, put one of his country’s electronic voting machines into the hands of Halderman and a Dutch colleague. These machines had become a source of national pride, a symbol of India’s modernity, and the government was resisting critics and keeping security inspections private. But the whistleblower knew better. Halderman and his collaborators readily exposed numerous vulnerabilities and made their findings public.

Halderman’s Indian colleague was later held and questioned by police about his complicity. When allowed a phone call, he contacted Halderman, who possessed both the presence of mind and the steely defiance to record the conversation and disclose its contents on Freedom to Tinker, a blog he had co-founded with Felten several years earlier.

Halderman’s faith in truth was vindicated. Public opinion, fully informed, turned against a government suppressing scientific inquiry, and the judge in the Indian researcher’s bail hearing not only set him free but hailed his patriotism.

But when Halderman returned to India several months later to lead an election security conference tutorial, his visa triggered a warning to deny him entry and return him to his point of origin. This time Halderman made a call. His insider-friends said they’d try to contact helpful authorities — and in the meantime Halderman should do whatever he could to delay being placed on the next plane back to the States.

“As a frequent traveler, there are things you learn to make the experience more efficient,” Halderman says. “I just did opposite.”

Halderman’s delaying tactics included claiming several times to have lost his passport; forgetting to remove liquids from his bag before passing them through the scanner; and, when asked whether anyone had given him anything while packing, Halderman answered, “Why yes, someone did — and come to think of it he may have been Pakistani, and I think it was ticking!”

Halderman laughs at the memory of officials ripping apart his bag only to be informed, once they had repacked it, of a secret compartment — and the process was repeated.

“At the end I was literally sitting on the floor as these two people were pulling me by the arms toward the plane,” Halderman says. “And at the last possible minute these immigration people appear out of nowhere and say we’ve just gotten a phone call from someone at the ministry: ‘You can stay the night; we’ll decide what to do with you in the morning.’”

In the morning, a political compromise was struck. Halderman was allowed entry to attend the conference, but he would not be permitted to give his talk concerning India’s vulnerable voting system.

The airport ordeal — which was reported in a local Indian newspaper and in the Ann Arbor News — may have been “a little scary” when it happened, Halderman allows, but he dismisses the notion that his resistance took courage.

“They had their job, and I had mine,” he says.

And living through it unscathed made him more aware of the impact his work could have. Despite initial resistance, Indian law now requires that a paper trail confirm electronic voting results.

“I think people are very easily scared,” Halderman says quietly. “Maybe more easily than they should be.”

Though Halderman says he spends so little of his time on election-related work that it’s “almost a hobby,” his long experience and world-class renown nonetheless landed him among the handful of experts overseeing the aborted 2016 U.S. presidential election recount process. (Because of what he characterized as incorrect media reports describing his role and his views, Halderman published his own piece to “set the record straight.”)

Now that Halderman and his colleagues have spent the last decade exposing electronic voting vulnerabilities, approximately 70% of voting precincts nationwide have some form of paper ballot. But in a year in which the election was so close, its result (based on pre-election polling) so surprising, and a foreign government was suspected to have interfered, Halderman found it “remarkable” that there still was no systematic plan to look at that paper.

The recount was not completed due primarily to partisan wrangling — something Halderman’s come to expect. In Estonia, the party out of power called the electronic voting system a “tool of the devil” while the party in power called Halderman a “communist” for exposing its flaws. In Australia, his colleague was threatened with loss of her university job merely because she joined Halderman in identifying its system’s weaknesses.

“It’s how politicians react when you call into question the machinery that got them elected,” Halderman says. “People in power see this first and foremost as a threat to their legitimacy.”

Though a truncated process, Halderman and Bernhard gathered enough evidence to support the integrity of the 2016 presidential election — though not enough to definitively rule out a cyberattack. They also found the system more vulnerable to attack than they had suspected, and they’re continuing to advocate for improvements in a U.S electronic voting system that is “lower on the list [among systems worldwide] than we should be, given what’s at stake in our elections.”

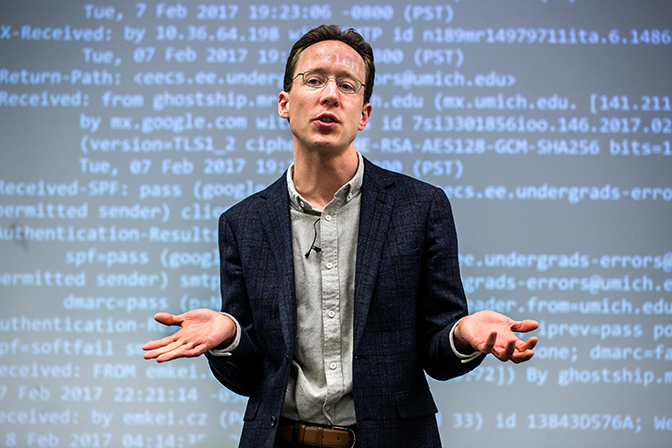

No matter the results, Halderman believes this work may have motivated the racist, anti-Semitic, threatening messages that were posted under his name on a Michigan Engineering-based computer science listserv, late in the evening on February 7, 2017. Students immediately gathered outside the house of University of Michigan President Mark Schlissel — and Halderman joined them.

The attack was a “spoof” — the email header was forged so that the messages appeared to have originated from Halderman — as opposed to a “hack,” which would have required an actual security breach and takeover of his account. In a brief public statement nearly immediately following the incident, Halderman said the “spoofed” emails “appear to be a cowardly action by someone who is unhappy about the research that Matt [Bernhard] and I do in support of electoral integrity.”

Over the next several days Halderman largely tried to go about his business as usual (notwithstanding various on-campus demonstrations and FBI and other investigations into the identity of the perpetrator). He sought to use the incident as a teachable moment for students in his computer security classes by lecturing about the importance of both identifying a troll and not responding emotionally, because that’s precisely what the attacker seeks.

Still, Halderman’s characteristic calm was momentarily punctured as he expressed concern for his students — and when he paused to consider the craven use of his persona to manipulate, and to invoke hate and fear. For Halderman — whose more expansive notion of “digital democracy” contemplates how computer technology impacts access to information and thereby affects public opinion — this was an especially disquieting incident.

Certainly there are basic maneuvers anyone can and should perform to harden computer security. Encrypted messaging. Two-factor authentication. Reasonable password practices. But that’s for mere mortals. Ask Halderman what he and his group do to prevent spying and you’ll get a steely response: “We do different things than you. We do certain special things.”

Halderman has been keenly aware since his encounters in India that “the stakes keep getting higher.” Today, he says, computer security is “in many ways about mediating the balance of power between the individual and the state.” And the state’s methods of conducting mass surveillance, or of censoring content, are more sophisticated and aggressive than ever.

“So I like to put my finger on the scale where I can.”

“Technical-social trends” such as “cyber warfare, governmental use of computer security problems in times of war, large-scale threats to privacy” are dreadful and worrisome, Halderman says. But not so much that they keep him up at night.

Bernhard describes Halderman’s attitude: “The world’s on fire all the time, so you may as well have fun while you go through it.”

This makes Halderman laugh out loud. “But I don’t believe ultimately that the world is going down in flames,” he says. “And the only reason I don’t believe it is that there are a lot of people working very hard, including us, to make sure it doesn’t.”

One example of this hard work, which Halderman says he’s most proud of, is Let’s Encrypt — the result of an ongoing mission to secure literally every website on the Internet.

HTTP, the foundational protocol of the web, was first made more secure beginning in the late 1990s with the introduction of HTTPS. But it has remained complicated and expensive for many websites to obtain HTTPS status through the existing certificate authorities. So beginning in 2012, Halderman enlisted numerous partners and sponsors to develop a non-profit certificate authority that makes the switch to HTTPS not only easier — automatically deploying in seconds, with one command — but free.

Within six months of its public launch in December 2015, Let’s Encrypt had become the world’s second largest certificate authority. And today, based on reasonable metrics, it’s already become the world’s largest.

Another security-enhancing invention: A very fast Internet-wide scanning methodology that was jump-started when Halderman asked then-PhD student Zakir Durumeric to “probe every computer on the Internet and come back with the set of public keys used for cryptography on all of them.”

This seemed a nearly impossible task, especially for a first year graduate student — like the Wizard of Oz telling Dorothy to return with the Wicked Witch’s broomstick. Yet when Halderman next heard from his student — a mere two weeks later — “he was on a path to the solution.”

Durumeric used existing tools in ways that eventually led to the creation of a new one called ZMap, enabling researchers to map the entire public Internet Protocol space in just hours.

The few prior attempts to accomplish anything similar were all extremely expensive and time consuming — epic undertakings featuring clusters of computers and experienced researchers who nonetheless completed just a portion of the intended task. ZMap reduced the cost and time by orders of magnitude, which Halderman credits in part to having built it with this specific application in mind, rather than repurposing something never meant to traverse the entire Internet. And it takes a “shotgun” rather than a “sequential” approach.

“We ask questions as fast as the network will go and let the responses come back whenever they do,” Halderman says. “But that’s okay; we’ll get that information later.”

Halderman likens ZMap to a weather satellite for Internet security, continuously gathering vast amounts of data. That information has transformed a largely anecdotal method of discovering and repairing Internet security problems into an empirical science so that problems can be more efficiently identified and solved.

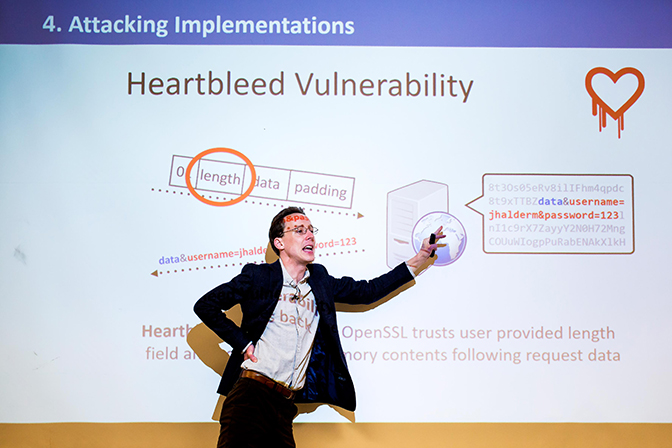

Before ZMap, an attack on a widely-used form of cryptography might not have been fixed until it could be determined what else might break in the process. Now that knowledge — including how many major sites are implicated and how many users are vulnerable or compromised — is immediately available. And new attacks occur every day.

“We can watch as a botnet grows and changes,” Halderman says. “That ability to create the historical record is a large part of the value.”

There long had been speculation about the various ways in which the National Security Administration (NSA) was conducting its surveillance activities. Then, in 2013, Edward Snowden’s sweeping document dump revealed that even the most wild-eyed theories were true.

At first Halderman and his colleagues were both devastated and disgusted by the nearly incomprehensible reach of the grab — and the amount of money that must have been spent on it.

“It took a while to digest,” Halderman says.

But by 2015, Halderman and a sizable group of collaborators — including several Michigan students and a number of colleagues from a handful of other institutions — published the revelatory “Logjam paper,” based in part on the Snowden disclosures, that answered the question everyone had been asking: How did the NSA break so much encryption that cryptographers had believed was virtually unbreakable?

The key to the paper, which Halderman calls “one of the most satisfying things I’ve ever done,” involves the Diffie-Hellman key exchange, which, ironically, was the algorithm widely advocated as a defense against mass surveillance. As Halderman explains in the Freedom to Tinker blog Diffie-Hellman users must first agree on “a large prime number with particular form.” But standardized primes had become commonplace, which left Diffie-Hellman vulnerable to being “cracked” with just one enormous calculation.

Halderman concedes he “can’t prove for certain” that this is what the NSA does. But that “enormous” calculation, conservatively estimated, would cost an equally enormous amount to complete. And among the Snowden trove are budget documents that make it clear that such an NSA investment is both affordable and likely. Halderman says he’s “been told” that NSA officials are not exactly pleased with his work.

It’s now well known that the NSA seeks to be able to intercept anything at any time. What it intercepts and investigates should depend on what it believes is in the nation’s interest at any given time. But how many others are capable of doing the same — and what are our protections, Halderman asks, “against a U.S. administration with a lenient view of its constitutional obligations?”

Since the paper’s publication, all web browsers have raised their minimum security standards, and the next version of TLS — the cryptographic protocol that underlies HTTPS — will be significantly stronger as well.

And now the Department of State has awarded a multi-million dollar grant for Halderman’s most ambitious undertaking yet. Michigan is leading a major multi-institutional project — including Halderman’s former PhD student at the University of Colorado, colleagues at the University of Illinois and researchers at the development giant BBN Raytheon — to thwart attempts to censor access to online content.

This concept of censorship resistance, using a method called decoy routing, “is a radical idea that we’re trying to make real,” Halderman says.

It first came to Halderman in 2011, but even after several years and more than one iteration — including a prototype that has provided basic service to more than 100,000 clients — “I’m still amazed that it works,” Halderman says.

That’s because the basis of decoy routing contradicts the core “end-to-end” principle of how the Internet is supposed to work. This principle holds that nearly all of the Internet’s intelligence and complexities are at the edges of the network, where users reside. The network itself merely shuffles packets from here to there, without even knowing what’s in them. This “dumb” network might not even see all the packets and has very little time to do much with them, anyway.

Efforts to dodge government censors have involved the use of Tor anonymity software and Virtual Private Networks, but this “whack a mole” method on the edges has become increasingly ineffective. Instead, Halderman says, “We’re trying to do these very complicated things in the middle of the network, in real time, as the data is going by.”

Decoy routing, in essence, would attach “decoy” routers to servers in various strategic junctions of the Internet backbone. To visit a banned site within a censor’s network, a user would install encryption software to establish a decoy connection with a non-banned site outside the censor’s network. This request would look allowable to the oppressive regime, but on its way to the censor-allowed site it would pass through one or more friendly ISPs, which would divert the connection, bypassing the censor and connecting it to the banned site.

Network hardware and processors are just getting fast enough to do this at large scale, and that’s the current state of the project: Bringing the current iteration of the decoy routing concept, called TapDance, to scale.

“As you start to learn more and more about technology you fall into a certain way of thinking about it,” Halderman explains, pacing his office before crawling up on a windowsill and looking out.

“You might call it conventional wisdom, but I think more precisely it’s the structure of abstraction that we use to make complicated technology amenable to thought,” he adds, hopping down and prowling around like a restless cat.

Halderman is putting that inside-out thinking to the test as he and his team attempt to build decoy routing and establish incentives for Internet Service Providers, compensating for risks they could incur by agreeing to place decoys along the backbone.

The team is aware of proposed and potential countermeasures, which it’s already taking into account. But either way decoy routing is a fundamental advance that will put those fighting censorship in a much more advantageous position than before.

“And this must be done,” Halderman says, because “it’s not certain in the longer term if the Internet will be dominated by the distribution of information, or by the control of it.”

Over the years, Halderman says he’s learned not to be so afraid of people telling him he’s crazy — or of being criticized. And to be careful about speaking with confidence about things he doesn’t know for sure.

“I like being right when I’m saying things in public. Your risk is reasonably controlled if you’re correct,” he says.

And he holds out hope.

“Security as a whole is getting stronger, especially over the last 10 and five years.” But those attacking us tend to be more powerful: Governments and large-scale organized crime rather than individual — and relatively innocent — vandals.

“It’s not just about protecting our social security numbers, or even about our physical security. It’s about the future of democracy. It’s about the international balance of power. It’s about liberty and privacy. It’s about national security. And it’s about the future shape of the world.”

“Those are the big questions,” Halderman says. And that’s where his focus will remain.