Wunderground.com: Democratizing weather

Harnessing the early internet and bringing real-time weather to our daily lives.

Harnessing the early internet and bringing real-time weather to our daily lives.

It’s Monday, August 19, 1991. Hurricane Bob is roaring up the coast of New England and the public’s everyday understanding of the weather will soon be forever changed.

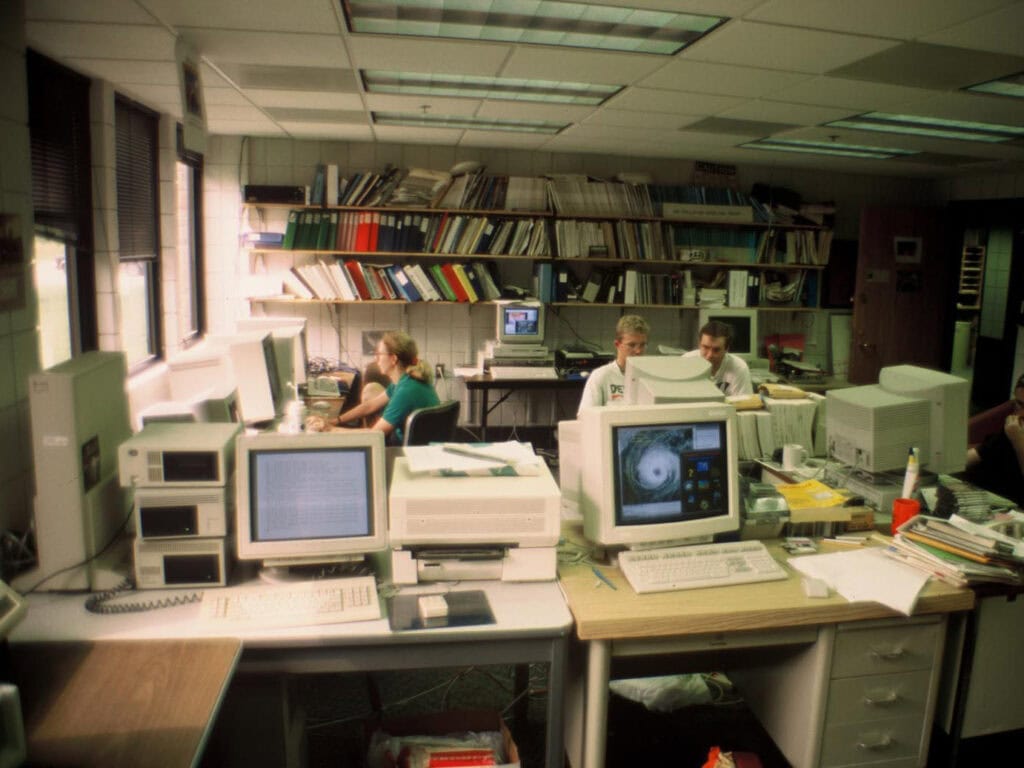

In the Space Research Building on the University of Michigan’s North Campus is a single Sun 4/110 workstation taking live satellite data from the National Weather Service. It organizes that data it into a simple, menu-based program and makes it available to everyone on the growing internet.

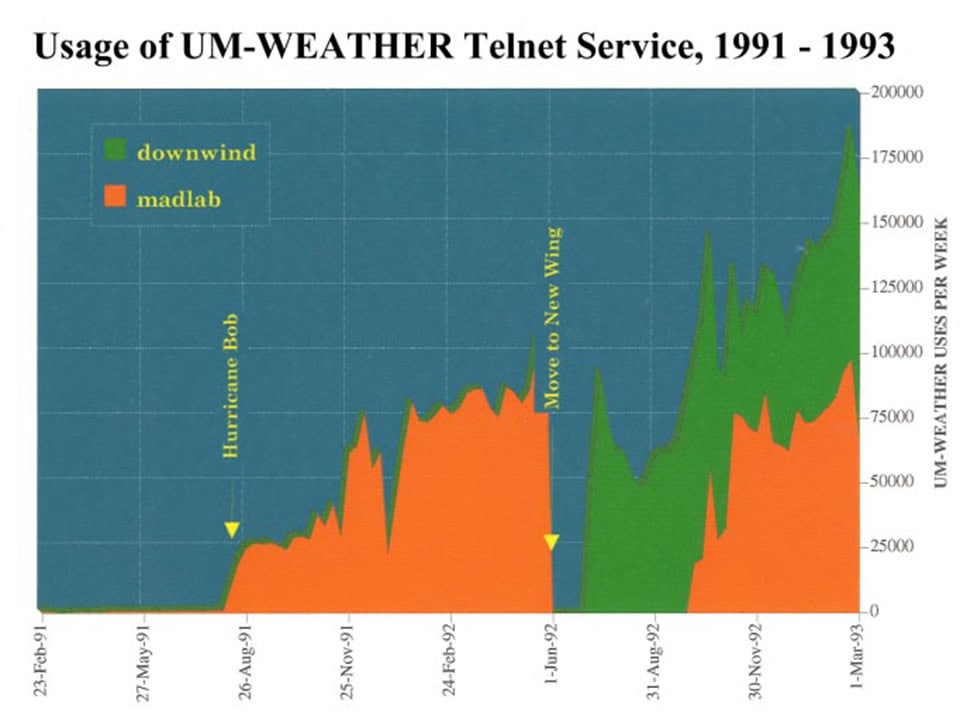

This real-time weather resource, referred to as UM-WEATHER, is the first of its kind, and not many people know about it. It had barely 100 weekly users since going live back in May, but with Hurricane Bob approaching, word of mouth boosts weekly usage to 25,000, with no slowdown in sight.

And the growth of UM-WEATHER would continue through 1995, when it would join the World Wide Web and eventually become the widely popular weather website still in use today: Weather Underground.

Before Bob, There Was Hugo

Hurricane Bob was not the first major hurricane to have influenced the creation of Weather Underground.

“Kind of a funny thing,” said Jeff Masters, co-founder of Weather Underground and creator of the original UM-WEATHER application. “Hurricanes were important in my career.”

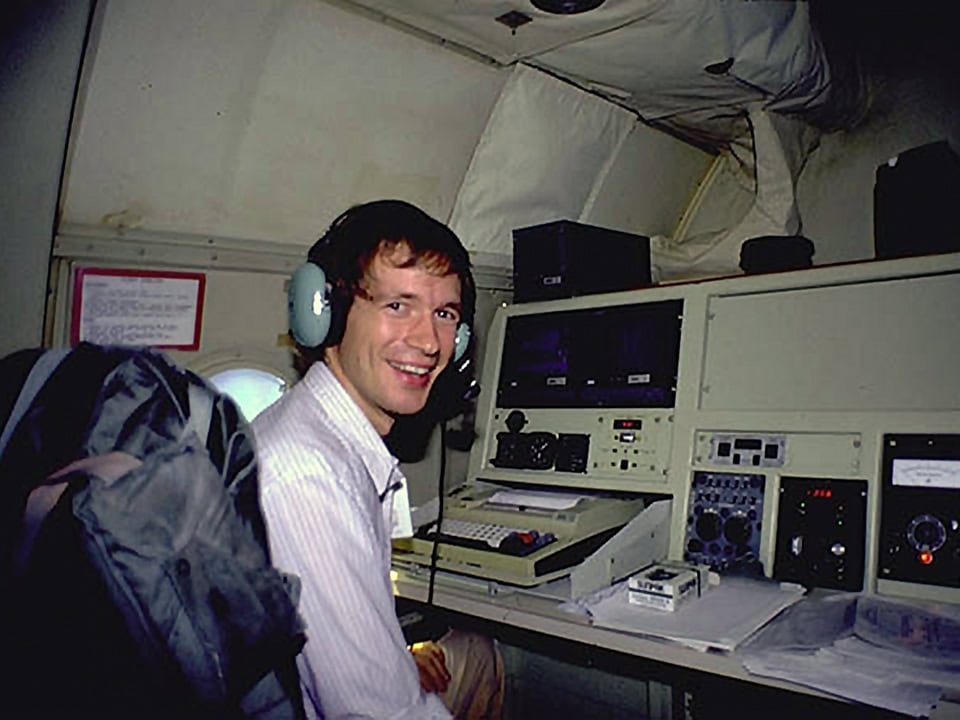

After earning both his B.S. (‘82) and M.S. degree (‘83) in meteorology from U-M, Masters decided to study weather up close. He joined the Hurricane Hunters, a research team within the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). As a flight meteorologist, Masters helped the group conduct studies aboard specialized aircraft of ocean winds, winter storms and, of course, hurricanes.

And in 1989, with Hurricane Hugo, Masters may have come a bit too close.

The crew, as usual, flew its aircraft into the storm and through the eyewall, recording various measurements. But this storm was much stronger than anticipated. The turbulence, more than five Gs of force, was extreme, and the plane almost lost two engines from the same wing. Miraculously, the pilots navigated out of the hurricane and returned to shore, with no passengers seriously injured.

After that experience, Masters viewed academia as a welcome change of pace.

It’s All Here

In 1991, Masters returned to U-M to study air pollution meteorology, but he also was curious about this growing communications tool called “the internet.”

And as it turned out, Ann Arbor was the ideal place for a meteorologist to build the very first real-time internet weather service.

The University of Michigan was the hub of the nascent internet at that time, and its North Campus home to many brilliant network engineers.

Meteorology, further, was and still is uniquely offered within Michigan Engineering — it’s a science degree at most other schools — and that’s largely due to Michigan’s long history of designing and building tools and instruments for the application and study of weather, climate, atmosphere and space, beginning in 1854 with the Detroit Observatory and continuing with the Greenland Expeditions in the late 1920s, Gerald C. Gill’s anemometer designs in the 1960s and 1970s, and the launch of CYGNSS in 2016.

It also didn’t hurt that on top of the Space Research Building was a satellite dish that received data directly from the National Weather Service.

Masters noticed all of this.

“I have all of the world’s weather data here, and a way to get it to everybody,” he remembered thinking at the time. “We’ve got to connect these up. Nobody has done this yet.”

Perry Samson, now an Arthur Thurnau Professor of Climate and Space Sciences and Engineering at Michigan, was Masters’ faculty advisor — and he gave him that opportunity.

“I really just wanted to get weather information for my nine o’clock class,” admitted Samson. “What I had been doing was recording some weather briefing they had at seven in the morning on TV with a VCR, and I’d bring that to class, and it was terrible. The video was terrible.”

And so as a project for his Interactive Weather Computing class, Masters learned how to write a text-based program that would take in live weather data, interpret it, and display it in an easily navigable format.

“I remember that being quite astonishing,” Samson said. “Now I could walk into class and actually speak with some confidence about how there’s a nasty storm coming for Duluth tomorrow.”

At first, Masters’ new program was only accessible on the University’s internal network. But having Merit within walking distance (the state and federally funded internet group housed on North Campus) allowed for a quick solution.

“They wrote this little sub-routine for me, and I plugged it in, and presto,” said Masters. “It would be available to anybody on the whole internet, worldwide.”

Build it Bigger

By the time Hurricane Bob hit in August of 1991, Masters had added many new functions to his UM-WEATHER program, but it was still just a class project. If it was going to take on more users and be competitive in the future, he and Samson needed to devote more resources to it.

Lucky for them, someone else took notice.

“It was one of the few times in my life where the National Science Foundation (NSF) called me and asked me to write a proposal,” Samson said.

And so they wrote a proposal and submitted it, and at the last minute, someone from the NSF wrote back and suggested Samson come up with a better name for the project.

He chose Weather Underground, a “tongue in cheek” nod to the 1960s radical student organization that also was founded at U-M.

“I regretted that, immediately,” said Samson.

“That was the era where you could name a company Yahoo and get away with it,” Masters said. “So sure, why not name your company after a terrorist group? Later on, when I watched the documentary about the Weather Underground…those guys were not so great.”

Either way, the name stuck, and the funding they received from the NSF enabled Samson to hire two computer science students — Alan Steremberg (B.S.E ’94) and Chris Schwerzler (B.S.E. ’96) — to work on the project, as well as Jeff Ferguson, a staff member at the time.

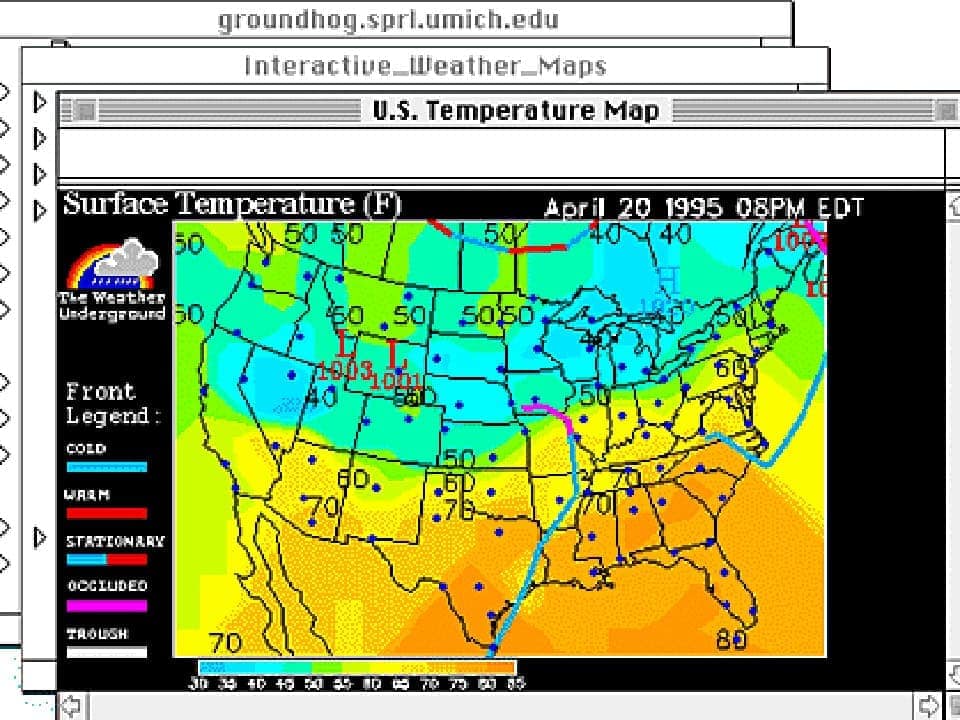

With the grant, the focus of the project shifted slightly to build weather software for K-12 classrooms to teach students about climate and weather. So the text-based program became predominantly visual. But this was before the World Wide Web — and web browsers.

“My vision was that we could have a weather map in HyperCard that would be interactive,” said Samson. “This was my wild idea. And Alan Steremberg had both the skill-set to understand there was a better solution of how to do this, and the politeness not to call me an idiot to my face. So he went on and made a Gopher client.

“But this Gopher client then became an interactive map where you could roll-over a city and actually see the current weather in that city. And this was unheard of in 1993.”

So much so that it won Apple’s Cool Tool on the Internet award. But the celebration was short-lived.

“Then suddenly the University of Illinois came up with this web browser (Mosaic), and almost immediately we went, ‘Oh crap,’” said Samson. “We just went down the wrong road. So we tried to catch up.”

During all of this digital turbulence, the NSF project continued, and Samson and his team developed various weather curricula for K-12 classrooms, and experimented with many of the innovative technologies of the early 1990s.

But eventually, the funding ended, and many of the students graduated. Steremberg went to Stanford, where he invited the others to join him in turning Weather Underground into a real company. Samson remained at Michigan.

In 1995, Weather Underground launched the website wunderground.com, initially offering daily forecasts and hourly weather conditions for 550 U.S. cities.

In 2001, the site began hosting a network of personal weather stations, giving users around the world the unique opportunity to submit their own local weather data. In early 2017, there were more than 250,000 personal stations linked to Weather Underground.

“A lot of people are very passionate about weather,” said Masters. “If you can get them reporting in their weather data, maybe they can add to the general wealth of data people want to see, down to the backyard level.”

“It’s no longer a top-down sort of business or endeavor, it’s a community endeavor. And I think that was a revolutionary sort of way to look at things — both from an educational point of view and a business point of view.”

That level and integration of data will only continue to grow today, especially with the purchase of Weather Underground by The Weather Channel in 2012, and then by IBM in 2016.

IBM is certainly well-known for combining data rich resources with its artificial intelligence project, Watson.

“It’s going to be really cool going forward the next few decades to see just how detailed we can get weather information — how fine-scale, and how useful as well,” said Masters.

Masters has stepped away from development at Weather Underground and is more focused again on education and on promoting productive discussions about climate and weather, and the site provides an important space for that. Back in 2005, Masters started a blog on the site and continues to post nearly every day.

“I’ve got my hands full just keeping track of what the weather is doing now — the research that’s going on about how to expect a change in the future,” said Masters.

“That’s perhaps the most important aspect as far as our service to our audience goes. I mean, we’re in serious shape as far as how humans are changing the climate.”

“It’s going to be a big challenge for society to adapt to this changing climate, and I need to do everything I can to help prepare people for that future, and make them simply believe that the science is correct.”

Aside from Masters’ musings about the future, he still holds a deep nostalgia for his time at Michigan.

“It was a bunch of talented, creative people in the right place at the right time with all of the full resources of the University behind them,” said Masters. “It wouldn’t have happened without Perry Samson being this entrepreneurial, ground-breaking professor.”

Samson, still a Michigan professor and still pushing unique ideas, shares Masters’ sentiment — for the most part.

“The University of Michigan is a great place to do this wild entrepreneurship,” said Samson. “Students seem to enjoy doing it, and they have the skills to do it — people like Jeff, Alan, Chris and all the others. I was able to find and bring these talented students together out of necessity and a bit of luck, but all credit should go to them because they’re the ones who really did all the work.”

“My contribution is the name. You’re welcome.”