Which Way to Mars?

Is a trip to Mars closer today, or as far away as ever?

Is a trip to Mars closer today, or as far away as ever?

Sputnik beeped; America responded. That’s one version—important and compelling—while to others the 1969 moon landing might have been not much more than an expensive Cold War stunt. But Apollo elevated everyone’s expectations about the possibilities of human spaceflight.

Nearly a half-century later, those times seem like lightning in a bottle rocket—never to be replicated—and no one has traveled beyond low earth orbit since the last Apollo crew rocketed to the moon on December 17, 1972.

Have recent developments brought us closer— or is a trip to Mars, once considered inevitable, as far away as ever?

On June 10, 1962, an Ann Arbor News story about the burial of a 2062 time capsule took note of a local Bendix Corporation scientist’s predictions: A Mars landing by 1985, Venus by 1990 and Mercury and Jupiter by 2000. “These achievements,” the scientist added, “will probably be accomplished with relative ease if technology continues to develop at its present rate.”

And this was seven years before Neil Armstrong took that one small step expected to be a giant leap for mankind.

So why have we still not sent humans any farther than the moon? It’s an especially surprising result, given that the far-reaching Apollo program and its culture of innovation inspired an entire generation of aspirational scientists, engineers and astronauts. It spawned new and still-thriving industries, many of whose discoveries, products and services still resound today. At its peak, no fewer than 20,000 separate companies were employing approximately 400,000 people in support of Apollo missions.

“The whole aerospace industry as we know it today comes out of Apollo,” says Michigan Engineering’s Lennard Fisk, Thomas M. Donahue Distinguished University Professor of Space Science. “It created the infrastructure for aerospace we’ve depended on ever since.”

But that “one small step” also was the one that beat the Russians to the moon—and ended the Space Race as hastily as it began.

Contrary to nostalgic remembrance, public support, even during Apollo’s apex, rarely exceeded 50 percent. And since the battle with the Russians was won and the war in Vietnam still raged, funding for Apollo already had declined—eventually falling by nearly ten-fold, to a low-level mark where it mostly has remained.

With Kennedy’s call to space a fading decade-old memory, the public’s attention had turned elsewhere, and in 1972 President Nixon terminated the Apollo program entirely—not only canceling the last three scheduled moon landings but also discontinuing plans for a late-1980s NASA mission to Mars.

Nixon considered several options to present as his own vision for U.S. space travel—a shuttle program; a permanent space station; colonization of the moon; and a Mars landing. Nixon chose only the shuttle program, which progressed throughout the 1970s, with little momentum for a trip to Mars developing under either the Ford or the Carter administration.

As the shuttle began to fly, Reagan sought to revive enthusiasm for human spaceflight. But in 1986, the Challenger shuttle spacecraft—whose launch was broadcast live and in color—disintegrated moments after takeoff, killing all seven crew members, including teacher Christa McAuliffe. The nation recoiled in horror—and its appetite for even riskier missions, if ever in evidence, vanished. Yet when George H.W. Bush was elected just two years later, he would propose a bold return to the Moon—followed by a trip to Mars. But those proposals never went anywhere.

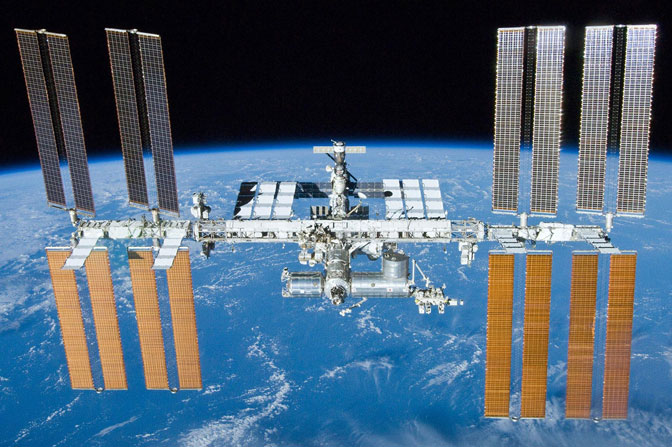

Clinton continued the shuttle flights, and began construction of the International Space Station (ISS), but he restricted U.S. human spaceflight to low earth orbit by specific presidential directive. In 2003, the space shuttle Columbia disintegrated upon re-entry into the Earth’s atmosphere—again killing all seven crew members—and the following year President George Bush announced the shuttle’s termination, effective by the end of the decade.

In 2004, the U.S. would soon be without a spacecraft even to bring its own astronauts back from the ISS. How would NASA ever be capable of sending anyone all the way to Mars?

hough President Bush grounded the shuttle, he otherwise advocated for an ambitious space program, including robust and sustainable robotic explorations. NASA has launched several successful robotic missions to Mars this past decade, in no small part to prepare for follow-on human missions—even though NASA’s human spaceflight trajectory continues to remain in doubt.

eak compromise the Bush administration called Constellation: A new capsule and rocket, developed for only a brief visit to the moon before a subsequent, direct trip to Mars.

Though the Constellation capsule and rocket also were intended to replace the shuttle, NASA nonetheless simultaneously invested in a commercial transport program designed to help commercial firms develop other potentially viable and less expensive means of travel to and from the ISS. Despite initial miscues, missed deadlines and underfunding difficulties, numerous firms competed in this program, and several would grow and develop beyond expectations.

All the Congressmen said you still have to build the rocket because it employs people in my district.

Former Deputy NASA Administrator Lori Garver was one of the chief advocates of the commercial transport program, and NASA Administrator Charles Bolden favored it because it enabled NASA to better focus its efforts on exploration systems intended to eventually send humans to Mars. But the Constellation space system, proposed for that precise purpose, never received sufficient funding, and it languished, severely behind schedule—which is one of the reasons why Obama sought to scrap it entirely as soon as he took office.

Fisk says Obama was inclined to take a step back to examine potentially new technologies—an opportunity to “stop building your grandfather’s rocket and ask whether there’s a better way to do this.” But Congress resisted on the basis that the move would result in the loss of decades of institutional knowledge in human spaceflight—and because radical change would cost its constituents their rocket-building jobs.

“All the Congressmen said you still have to build the rocket because it employs people in my district,” says Fisk.

Obama relented, and key components of Constellation were resurrected, albeit under new names. In 2010, Congress authorized the Space Launch System (SLS): A heavy-lift rocket to accomplish a human flight to Mars in the 2030s. NASA has since devised an interim robotic mission to capture an asteroid and return it within the vicinity of the moon, which a crew of four astronauts would then visit—presumably sometime in the mid-2020s.

The SLS is NASA’s current roadmap to Mars. But from its inception critics called it the “rocket to nowhere” because its destination and flight schedules have been vague, and because its development costs devour so much of its budget that there’s nothing left for payloads.

Garver is one of those critics. In January 2014, just months after stepping down from the NASA post she had held since 2009, Garver told NPR’s Diane Rehm that “NASA needs to push and do new things, and be less about the status quo and the already-developed constituencies and keeping them fed.” Later, when asked by Rehm which NASA programs should be cut, Garver named the SLS.

Bolden has heard the naysayers and has remained a staunch defender of the SLS. During his keynote address at the Humans to Mars Summit in April 2014, Bolden told his critics, “Get over it.” But he also seemed open to new ideas. “This is the path we have chosen,” Bolden said. “Help us tweak it.”

A Congressionally-mandated National Research Council (NRC) study concluded in June 2014 that the SLS on its present path is likely to result in “failure, disillusionment, and the loss of the longstanding international perception that human spaceflight is something the United States does best.” The NRC report made a case for reconsidering the moon as a stepping-stone to Mars, and for further engagement with the international community, and especially with China—even though federal law currently prohibits it. India, China and Japan all have made recent strides in human space exploration, and all are currently planning lunar landings.

Lauri Hansen (BSE Aero ’85) is director of engineering at NASA’s Johnson Space Center. During her remarks as a Future of Space panelist at Michigan Engineering’s September 2014 Aerospace Centennial, Hansen said, “Apollo was a competition. ISS was a limited collaboration…. To take the next big step we will need everyone as an integral partner.” And Bolden has said, “We cannot go to Mars without it.”

Fisk, recently elected president of the International Committee on Space Research (COSPAR)—established by the International Council for Science in 1958 to promote scientific space research and a free exchange of information on an international level—says COSPAR would help to promote an international effort, but at the moment it’s “all talk, no substance.”

The NRC also noted two other key ingredients lacking since Apollo—strong leadership and effective communication. This is why Fisk has suggested that it’s possible, if not likely, that the next presidential administration will cancel SLS as unsustainable, just as other administrations have promptly undone what their predecessors have pushed. But Bolden strongly warned against that during the Q&A session following his Humans to Mars Summit keynote address.

“We made a decision,” Bolden said. “Some people in this room don’t like it. But we’re on our way, and you can either go with us, or figure out how to start all over again. And everybody in this room, I think, knows what happens when you start all over again.”

A July 2014 Government Accountability Office report has warned that the SLS is dangerously underfunded. It specifically compared Apollo’s rapid launch pace with the SLS’s projected flight schedule—which currently consists of a 2017 maiden voyage and a 2021 encore. But if additional resources are necessary to set SLS on a sustainable path, such funds do not appear to be forthcoming.

In 2012 astrophysicist Neil DeGrasse Tyson testified before a U.S. Senate subcommittee that the nation needs a more ambitious human space exploration program—and more money to properly conduct it. During the Apollo era, Tyson argued, the crossings of space frontiers were so inspiring that they rendered STEM programs unnecessary—and those and other scientific advances stoked our economy with jobs that couldn’t be sent overseas because Americans were the only ones who knew how to do them. Apollo at its zenith comprised nearly 5 percent of the federal budget; NASA’s current allotment is approximately 0.5 percent. Tyson has launched a “Penny4NASA” campaign to help taxpayers ask their elected representatives to double NASA’s budget from a mere half-penny to a full one.

Bolden has acknowledged that getting humans to Mars by the 2030s will require “modest increases” in NASA’s budget. But he’s also ruled out Apollo-level funding.

“Reality is the budget,” Bolden said at the Humans to Mars Summit. “We are not going to get 4 percent of the federal budget to go to Mars or any other place. One percent would be a gold mine.”

It’s very much a kind of renewed grassroots level in space. I think that’s going to spark, and create some big things.

While the public sector has been lurching, stop-and-go style, toward Mars, the private sector has been pursuing its own course.

The first breakthrough occurred in 2004, at about the same time that President Bush announced the plan to terminate NASA’s shuttle program. XPRIZE—a non-profit organization created to encourage “radical breakthroughs for the benefit of humanity” through incentivized competition—had offered $10 million to the first non-governmental organization to launch a human on a reusable spacecraft twice in two weeks. The winner—SpaceShipOne, a suborbital air-launched space-plane developed by Mojave Aerospace Ventures (a joint venture between Microsoft’s Paul Allen and Scaled Composites, an aviation company led by aerospace pioneer Burt Rutan)—accomplished this feat on June 21, 2004.

Before SpaceShipOne’s historic feat, astronauts always had been sponsored and trained exclusively by governments—either by the military or by civilian space agencies. Suddenly, the field seemed wide open to private citizens.

James Cutler, Michigan Engineering associate professor of Aerospace Engineering and of Atmospheric, Oceanic and Space Sciences, says this do-it-yourself ingenuity has quickly become part of the youthful ethos. He and a team of Michigan Engineering students and faculty have been developing small spacecraft called CubeSats, and their simple format has enabled teams from established and startup companies, universities, and even high schools to send CubeSats into space on a variety of missions.

Cutler’s Michigan Engineering students are so excited about their projects that Cutler says he has to “send them home at night. I have to make sure they’re taking care of themselves, getting enough sleep. … We’re trying to do things that have never been done before … and it’s very much a kind of renewed grassroots level in space. I think that’s going to spark, and create some big things.”

Robert Gitten, a Michigan Aerospace Engineering sophomore, is one of those students. Gitten is a member of the Michigan chapter of Students for Exploration and Development of Space (SEDS), a student-led organization dedicated to expanding human space exploration. Gitten attended the October 2014 SEDS National Conference, where he and his fellow SEDS members were inspired by the exhortations of keynote speaker and longtime space activist Rick Tumlinson, cofounder of the Space Frontier Foundation.

“The idea that people should be living off Earth is really sinking into the public imagination,” Gitten says.

Organizers of Explore Mars, a nonprofit organization dedicated to sending humans to Mars within the next two decades, similarly claim they’re seeing attitudes change from “Mars-is-too-hard” to “Mars-is-doable;” and from “Mars-is-too-expensive” to “Mars-is-affordable.” Explore Mars’ mission is to “spread the word that Mars is a necessary destination for humans”—and numerous citizen-based efforts to Mars are already under way.

Mars One, for instance, founded in 2011, is a nonprofit foundation created to “establish a permanent human settlement on Mars.” Mars One plans to utilize existing technologies from proven suppliers, and it intends to finance its mission with individual and corporate contributions and from the not-yet-consummated sale of broadcast and advertising rights for its proposed reality TV show on Mars. Though intended as a one-way trip, more than 200,000 individuals registered for Mars One’s astronaut selection program when the opportunity first became available in April 2013. An October 2014 MIT study casts doubt on the plan’s feasibility, but Mars One organizers—including co-founder Bas Lansdorp, a wind energy entrepreneur—expect to send their first four astronauts to Mars in 2025.

We polled our Facebook followers about their interest in a one-way trip to Mars.

Inspiration Mars Foundation, a nonprofit company founded in 2013 by Dennis Tito (who became the world’s first “space tourist” when he paid to be transported to the ISS on the Russian Soyuz spacecraft in 2001), also intends to send a crew to Mars—not to land, or even to orbit, but to bring them within roughly the same distance from Mars as the ISS is from Earth. Though Inspiration Mars would be the first private company to accomplish a feat in space that no governmental agency has achieved, industry observers believe this mission may be among the most likely of the private ventures to succeed since it is merely a “flyby” of Mars using technologies that NASA and others have been using for years.

“Our huge national assets have reached their limits,” Cutler says. “NASA still needs to play an important role. Certain research facilities still need to be government sponsored. Huge thermal chambers, vibration test facilities, wind tunnels—there’ll always be a need for those. But the key question is, ‘Who does the innovation?’ It doesn’t take a nation as much as a vision and an engineer.”

Failure is not an option, and that limits exploration.

NASA’s commercial transport program grew slowly at first but has since developed into a nearly unqualified success. Due to the termination of the shuttle program, followed by the failure of Constellation, for several years NASA had to depend on the Soyuz for both cargo and crew transports to the ISS. NASA awarded cargo transport contracts to startup SpaceX, and then to the more mature Orbital Sciences, and on October 28, 2012, SpaceX completed its first successful commercial transport mission to the ISS. NASA still depends on the Soyuz to taxi its own astronauts, but in September 2014 it awarded crew transport contracts to SpaceX and Boeing, and the first commercial transports of U.S. astronauts are expected to begin in 2017.

SpaceX will be paid $2.6 billion while Boeing will receive $4.2 billion—for what NASA has said is delivery of the same set of crew transport services. SpaceX’s lower bid may be due in large part to its streamlined processes and in-house manufacturing capabilities, which means SpaceX should be able to continue to shuttle cargo (and within a couple of years, astronauts) to the ISS at costs much lower than those currently being charged by the Russians.

But SpaceX founder Elon Musk has said, “What SpaceX has done so far is evolutionary, not revolutionary.” The company is working on the Falcon Heavy rocket, which Musk says will “make the Apollo moon rocket look small.” Musk’s goal is to travel to and ultimately colonize Mars—perhaps within the next ten years—which will require not just lower costs or larger rockets but the “rapidly reliable reusability” of those rockets.

In October 2014, Musk announced that following its next ISS launch, SpaceX would have its rocket attempt what the company calls a “propulsive landing with precision” onto a giant floating platform in the middle of the ocean. Musk had said he didn’t necessarily expect the first attempt to be successful – and when it occurred on January 10, 2015, it wasn’t.

“There are a lot of launches that will occur over the next year,” Musk said. “I think it’s quite likely that one of those flights, we’ll be able to land and re-fly, so I think we’re quite close.”

Other companies are pursuing similar paths—with some of the richest and smartest people in the world bringing their considerable resources to the burgeoning private space industry. Blue Origin, created by Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, also is focused on reusable, rocket-propelled vehicles capable of vertical takeoffs as well as landings. Microsoft’s Paul Allen, who backed SpaceShipOne, has invested in Stratolaunch Systems, which is building a more cost-effective launch system that will employ a massive carrier aircraft to boost rockets into space. And XCOR Aerospace, founded by the much lesser-known Jeff Greason, is developing reusable rocket-powered systems, and soon will begin testing a spacecraft that takes off and lands like an airplane.

We are farther down this road than we have been in a long, long, long, long time.

NASA has nurtured its commercial transport participants with substantial seed funding in many cases, and with lucrative transport contracts in others. Without this program—and the ISS—these ventures would not have grown and developed so quickly, and it’s likely that none of them would yet be contemplating a mission to Mars. But many of them are.

“Private, well-funded citizens are more interested than ever in going to Mars,” says Cutler. “They have the resources, the drive, and the motivation. Mars is within their reach.”

Gitten also is excited by this rise in space entrepreneurism. “There are more rockets being designed right now than at any other time in history,” Gitten says. And while numerous other ventures also are making substantial progress toward Mars, Gitten says, “SpaceX is cutting metal right now in its own facility for spacecraft that will take us there.”

Many of these nascent space industry companies haven’t yet required public support beyond the financial backing of their investors and the continued patronage and partnership of NASA. But as the mission destinations move beyond low earth orbit and the ISS—and toward Mars and beyond—additional customers must be gained and maintained. And as partners potentially become competitors, matters could grow more complex. In the meantime, Bolden recently hinted at NASA’s willingness to partner with the commercial sector in future deep space missions.

Commercial firms also haven’t been subject to the scrutiny NASA has endured for decades—and there hadn’t been even a single significant public setback until an Orbital rocket, on an ISS re-supply mission on October 28, 2014, exploded seconds after takeoff. Orbital’s stock dropped 15 percent the next day. Imagine if a crew had been aboard.

History has proved the public’s intolerance for killing astronauts—and the effect that fear continues to have on NASA.

“Lessons from past failures have limited the scope and reach of new NASA missions,” Cutler says. “Failure is not an option, and that limits exploration.”

So NASA continues to build an Apollo-type rocket on a timeline and at a cost exceeding what was required nearly a half-century ago. In September 2014, NASA’s SLS program manager Todd May announced that the SLS “continues to make significant progress. The core stage and boosters have both completed critical design review, and NASA recently approved the SLS Program’s progression from formulation to development.” And on December 5, 2014, NASA successfully completed its first test of the launch, flight, and re-entry capabilities of the rocket and capsule expected to eventually carry astronauts to Mars.

Michigan Aerospace senior Sandro Salgueiro, who has been closely monitoring the SLS’s rocket progress, says, “From an engineering standpoint, this is a major milestone in terms of sending humans and other payloads that far into space.”

And certainly Bolden believes that the SLS and NASA, likely with some international cooperation, will lead us to Mars. As he told his Humans to Mars audience: “We are farther down this road than we have been in a long, long, long, long time.”

During her remarks as a Future of Space panelist at the Michigan Aerospace Centennial, NASA’s Hansen expressed the hope that many Michigan students would work with NASA to “put the first human footprint on Mars.”

Stephen Wasko (BSE Aero ’80), who returned to campus for the Aerospace Centennial, says, “That’s what we were told as students in 1980. Unfortunately, it all sounds overly optimistic, given the history. It makes you wonder: Are we still just fooling ourselves?”

“Who’s to say this is not another false start?” says Gitten. “It’s all speculation until the first rocket to Mars is flying. But this is the time. We’re going. This is the generation.”